Editors on Editing: What Writers Need to Know About What Editors Do (30 page)

Read Editors on Editing: What Writers Need to Know About What Editors Do Online

Authors: Gerald Gross

The editor has only so many points to play in any given manuscript, and he must decide which are the most important for every book he edits, establishing a hierarchy of changes that he believes the author must go along with. Roughly, I would group these changes as necessary, felicitous, and meticulous. It is not usually possible to work on all three fronts. In a manuscript that needs reorganization, new material, and substantial revision, it is a waste of time to fault the author for somewhat repetitious or awkward phrases; on the other hand, in a well-plotted novel that moves as smoothly as a canoe across a mountain lake, a poorly worded phrase will stick out like a discarded Styrofoam cup floating on the water.

The absolutely necessary changes are always of utmost importance and should not leave much room for discussion. These would include anything that is clearly wrong: omissions, weak organization and logic, factual errors, lack of balance, and the like. These problems weaken the core of the book and, if they are not addressed in the editing, open the book to criticism. In any manuscript with these problems, the editor must focus all his attention on them and may have to forgo some linguistic niceties.

Consider this excerpt from an obituary in the

New York Times

of October 27, 1989:

His wife, the former Susan J. Ault, died in 1983. They were married for 36 years.

He is survived by two daughters, Shirley Evans of Salem and Barbara Cleaveland of Alexandria, Va.; four grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

From the dates given, the subject’s older daughter could be no older than forty-two years old, assuming she was born in the first year of his marriage. For her and her sister, two women in their early forties at most, to have

three grandchildren is possible—triplets?—but not likely. This is the kind of statement that must be queried. Straightening this out is more important to the obituary than any other possible change.

The felicitous changes include substituting smooth phrasing for awkward language, heightening narrative thrust, and eliminating overlong citations that weigh down a popular work. Here the issues are less a matter of right and wrong than of impoving the manuscript and presenting the reader with a better book. The editor will point out repetition, distracting plot details, sentences that plod along in a dull subject-predicate-object pattern, paragraphs of dense, thickly worded sentences, paragraphs of rapid-fire five-word sentences that leave the reader no time to absorb their meaning. Compare the unedited and edited versions of this passage:

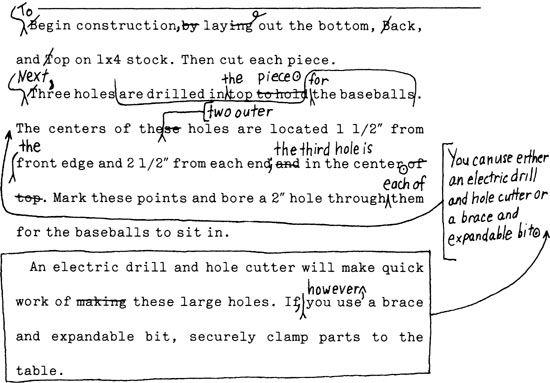

Begin construction by laying out the bottom, Back, and Top on 1x4 stock. Then cut each piece.

Three holes are drilled in top to hold the baseballs. The centers of these holes are located 1 1/2” from front edge and 2 1/2” from each end and in the center of top. Mark these points and bore a 2” hole through them for the baseballs to sit in

.

An electric drill and hole cutter will make quick work of making these large holes. If you use a brace and expandable bit, securely clamp parts to the table

.

Note that there were no technical errors in the original manuscript, nothing that had to be edited. Every editor, however, brings his own judgment and reading to bear on the manuscripts he edits, and this editor believed that readers might have difficulty following these telescopic instructions, especially with the drilling equipment discussed

after

the drilling instructions. In rewording the passage, the editor has slowed down the pace; in addition, he has moved the information about equipment. How does the editor query these changes to the author? In a marginal note he says, “Instructions a bit brisk for reader to follow. OK to slow down? If not, please recast.”

Note that the author’s attention is drawn to the change and that she is given the chance to reject the suggestion and reword the passage herself. The editor must query all changes that touch on content—which means everything except grammar, punctuation, spelling, and house style, which by contract the publisher controls—for the content of the book is clearly the author’s province. Frequently the query is a simple “OK?” for minor changes.

Fine points of language and phrasing and nuances of characterization are usually achieved only in manuscripts where there are few major revisions and changes. Here the editor can devote himself to making the language as

precise and meticulous as possible. Although the editorial suggestions here will probably be the most fastidious, the manuscript will probably be the least heavily edited because there are no major changes.

Almost all of the editor’s work on the manuscript is presented to the author in the form of queries. He formulates these queries from the questions that arise as he reads through the manuscript, questions that usually suggest revisions, cuts, amplifications, and the like. In most cases, the author has the final say over which of these questions she will address, so it is in skillful and persuasive querying that the editor states his case and hopes to draw out of the author the work needed to publish the best book possible.

Querying takes many forms, including face-to-face discussions, but two of the most common are the cover letter and the marginal note, sometimes combined as a letter with an attached page of specific comments. The letter and note serve two different purposes: The letter discusses general or repeated issues, and the note cites specific instances or passages.

In the cover letter the editor can discuss questions too lengthy or complex to be handled in a marginal note or issues that crop up so frequently that the author may be annoyed if the editor calls her attention to them every time they occur. For example, the authors of a rockhounds’ manual made several joking references, from their point of view, to inappropriate clothing worn by women on collecting expeditions (“Tell the little lady to leave her high heels home…”). Rather than query each potentially offensive passage in the manuscript, the editor used the cover letter:

I also think you might rework some passages that readers may find dated and possibly insulting; see checked passages on pages 12, 37, 62, 118, 214, 276–277, and 303.

Here is an excerpt from a masterful letter plus notes written by Saxe Commins, one of the formative editors at Random House, to S. N. Behr-man, author of a biography of Max Beerbohm.

Now, less than twenty-four hours after the arrival of the typescript, I must tell you that you are getting closer and closer in mood and selective detail to the impressionist portrait of Max both of us have in mind. Your own charm and unmistakable style are strikingly apparent on every one of the tentative forty-six pages, and the material is indeed rich if, until now, only suggested.

I still feel very strongly that it cries for expansion. …

It’s no favor to you to make so generalized a statement. Unless I can particularize you won’t be able to guess what I am driving at. So let me offer for whatever they are worth, page-by-page questions and suggestions, some sensible, some captious, to be accepted or vetoed, but at least a sort of agenda for our summit talks. To begin:

Page 1. It seems to me that much more can be made of Max’s and Herbert’s background by elaborating on Julius, Constantia, and Eliza, more or less as you did with the forebears of Duveen….

Page 2. Would it be possible to convey a little of the prevailing atmosphere in America, particularly in Chicago, when Tree put on

An Enemy of the People.…

Page 4. Would it be out of place to write in a sentence or two about

The Yellow Book

. It had quite a history. On this page you do give a little of the flavor of the essay, but I think it would profit by a few more comments almost in Max’s own vein.

Page 5. The references to Scott Fitzgerald and Ned Sheldon are dangling in midair. Unless you specify some of the similarities I’m afraid the comparison will be lost. And why not more about Aubrey Beardsley?

Page 6–7. The cracks at Pater are too good to miss. They make me want more. The gem-like flame should be blown on a little harder.

*

Commins’s skill in querying could enhance any editor-author relationship. Most important, he begins by reaffirming his own enthusiasm for the book, a vital factor in encouraging the author and thus in drawing the most from him. It is clear at every point that the editor and author are working for the same goal even if it may take a great deal of time and effort to reach it. The overall tone is one of help and interest. General criticism, which calls for expansion, quickly gives way to specific problems—omissions, repetitions, insufficient information—so the author knows exactly what he has to work on.

Note also how Commins takes advantage of his response as first reader and by extension suggests the response of other readers. Many of his page-by-page comments refer to himself or a reader. This approach not only envisions the manuscript as a finished book or article in the hands of its ultimate audience but also points out manuscript difficulties in a meaningful way. Rather than say to the author, “No one will be able to follow

argument here,” the editor can make the same point by saying, “Am having some trouble following argument here; please give example.” The difference is subtle, but by taking some of the burden onto himself, the editor is less condemning and illustrates the reader’s need.

Note the detail of Commins’s comments. A less attentive and considerate editor might dash off marginal exclamations like “vague,” “need more,” “anticlimactic”; instead Commins gives the author the reasons and arguments for all his suggestions. This leaves the author very little room to ignore or disagree with them, helping Commins get what he wants. I have seen editors scribble “right?” in the margin next to a questionable passage, with no explanation for the query. This seldom yields the response the editor wants. What if the author answers “yes” and gives no further evidence or authority? Worse yet, what if the author, bothered by the question, answers “no”?

Effective querying elicits the response the editor wants, and he must direct the author to it. After all, if the author has been vague or confused in his first draft, there is no reason to believe that, undirected, he will improve substantially the second time around. Thus the query must be carefully worded. Take, for example, this garbled paragraph:

In the nineteenth century, tuna was strictly chicken feed. This was not true of salmon, which was canned and widely available. One year the sardine catch fell short, and a sardine canner hit on the idea of putting up tuna. Canned tuna caught on immediately.

If the editor queries marginally “confusing; please clarify,” how can he guarantee a less confusing rewording? But what if the editor says, “Hard to follow. Do you mean salmon and sardines were both commonly canned and a sardine canner, lacking sardines and salmon, used tuna? Please add explanatory sentence”? Here the editor has laid the groundwork for the author, and if the author answers the query, the editor will probably get enough information to make the passage comprehensible or, at the least, editable.

…

And so, in the end, we return to the author-editor exchange, that long and rewarding process that results in the best book possible. How much work that takes from the editor depends on what kind of manuscript he has received from the author, but the more effective the editor, the less his work will show, no matter how much he has put into the process.

Editors are not authors, nor do they wish to be. What the best of editors wishes to be is the perceptive, demanding, energetic, and patient prober who can devote his particular talents and skills to the enterprise of working with authors to publish good books.

The Art of the Reasonable Suggestion

John K. Paine

J

OHN

P

AINE

is the senior manuscript editor for the NAL/Dutton wing of Penguin USA

.

Ms. Waxman’s goal in line editing is “drawing out the best book possible.” John Paine describes some of the most effective techniques and principles he uses as a working manuscript editor to achieve that high purpose in his short but sagacious essay

.

Believing line editing to be “the art of the reasonable suggestion,” Mr. Paine deems it essential that an editor learn yet another art to make the first one work with maximum effectiveness: “the art of communication.” He points out “two features in any editorial note that are paramount in building editor-author rapport. One is that an editor state, continually, what she

likes

about a work…. Second, the language employed should be that of a helpmeet.”