Edinburgh (28 page)

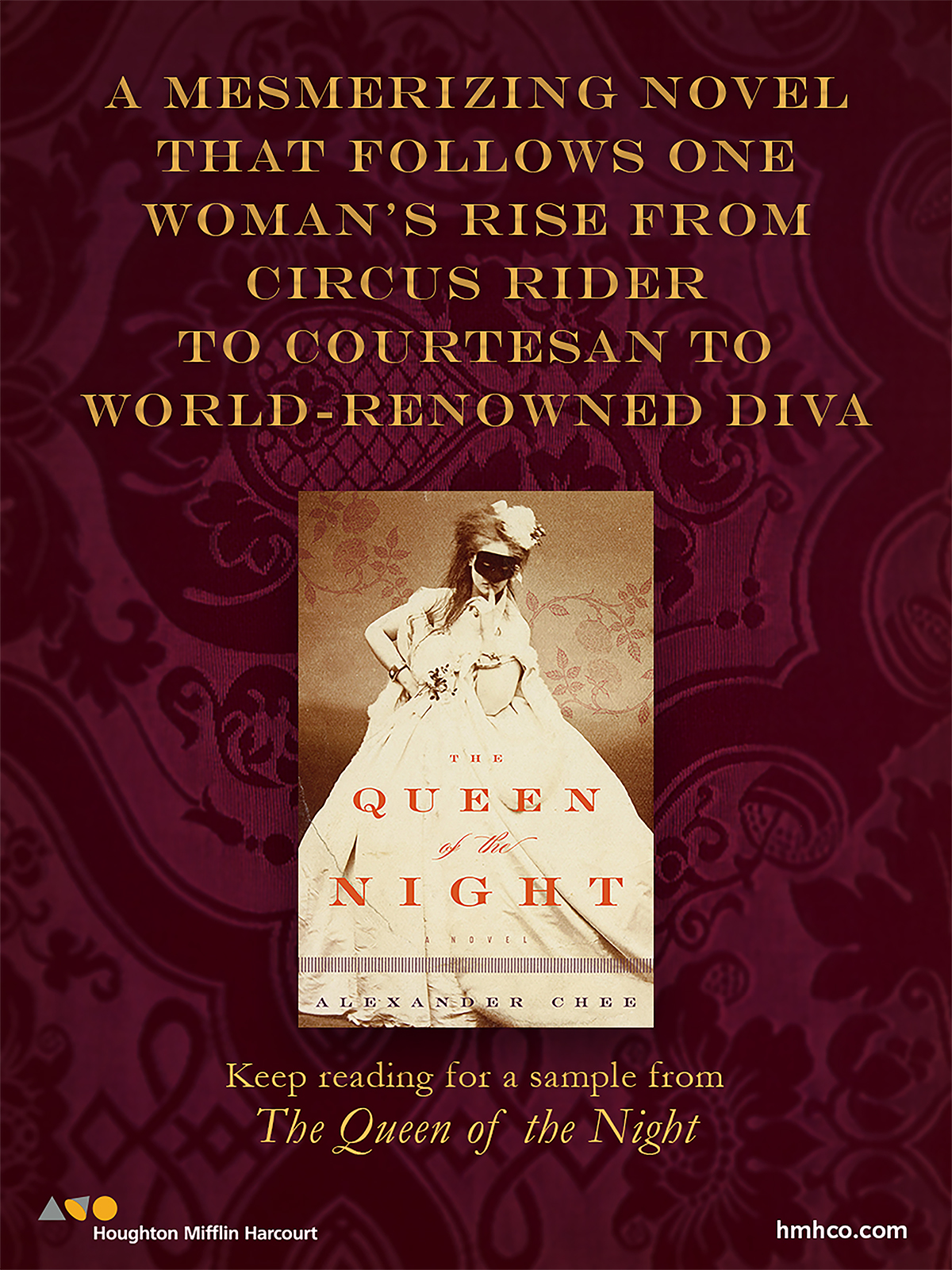

Authors: Alexander Chee

He went to New York, she says.

Who's he staying with?

I think he's staying with John Mark, she says. It looked like his number when I wrote it down.

Did he mention anything else?

Fee, why don't you call him yourself.

I dial the number. It was indeed John Mark's, my friend, whom Bridey had gotten along with better than I had. John Mark, I think, had loved me in secret for some time, and then scorned me underneath that love, and so when Bridey arrived, he could welcome him. They'd become friends quickly. Bridey picks up the phone. Caller ID, he says. Hello Mister. Or is it Mom?

How's John Mark, I say.

He's okay. He's been busy. He put a bid in on an apartment, and so we're sitting here planning the garden.

What does he want, I ask.

What everyone wants. Low-maintenance greens, regular appearances by flowers. This isn't what I want to talk about, though, he says, and I hear the scrape of something closing. It isn't even what you've called about, unless I really don't know you.

I need help, I say.

You're crazy. I used to think it was charming but now it's just dangerous. You call it love but it's just humoring you, that I do.

There's something you need to know, I say. I can't say it over the phone.

I need to know, he says. You know what I need to know?

What, I say, afraid.

I need to know, he says. I need to know what that was.

Come here to believe me. Come back.

That day, he says. When I met you. I thought you were beyond belief. My diaries are full of entries about you, before I knew you. Me guessing this or that, talking about the things I'd heard about you. I loved you even then. But now it feels like I was set up.

I watch the insides of my mother's house. All of this furniture, all of these boxes. All of this life. No, Bridey. You never said this, I say. But, more importantly. You were set up, just not by me.

He's a boy, Fee, he says. He's a child, even if he's a beautiful child, or a mature child. He's a child. I look at him and I wonder what he'll look like when he grows up. I want you to think about that, he says. I'll call you tomorrow. And then he hangs up. I look up to see Warden in the door, looking at me.

16

FROM THE OBITUARY

page the following day:

Eric Gorendt, of Lincoln Falls, died sometime early in the morning the night before, at the age of 52. He had recently been released on parole, electronically monitored, to finish serving a sentence of twenty years in prison for sexually molesting twelve boys in his charge as their choir master for the popular singing group the Pine State Boys Chorus. An accomplished director at an early age, he is survived by his parents and a son, Edward. The cause of death was listed as burning.

In the dark morning, still roofed in blue and stars, Warden nibbles a doughnut, wanders the doughnut shop. We've gone out to get the paper and I am thinking now of how we should leave. Never come back. I shuffle the paper shut and look around. No one else here, except the counterperson.

You think no one is going to suspect us, I say.

No, he says. I think no one is going to find us.

17

I LEAVE HIM

in a hotel room near the turnpike that night.

I check in, and he sneaks in once I've got the room open, so the clerk doesn't see. He's exhausted and so am I, and he falls back across the bed, arms over his head, in surrender, falling asleep almost at once. I look at him in the cheap yellow light of the room and take in the smell, of old smoke from the thousand cigarettes that must have gone out here. It's not us, I want to say. I want to wake him and tell him, that we need to escape this, that what he's done has trapped us and not freed us, but the planes of his sleeping face rebuke me, which is when I see myself in the mirror above the bed: tired, lonely, him stretched out below me, looking for all the world like I've knocked him out or worse.

You did this, I tell myself. Not him.

I don't want to be the one to turn him in to the police. I want him to do that or not. I want him to have the choice, to say he did it or not, but I want him to choose what happens next even as I do, as I walk toward the door and, leaving the key inside on the carpet, close it. From a pay phone I call the hospital and say I need an ambulance for room 322, that my friend has closed the door and won't answer and I think it's an emergency.

He's unconscious, the operator asks.

He won't wake when I call him, I say. I am lying only a little. What he needs to hear he'll never hear if I say it.

I roll the car down the drive to turn the engine over in the street. Drive off without headlights for the first two minutes, and then, when the headlights pick the night's hem up off the road, I head for Cape Elizabeth, for Fort Williams. There are empty houses over there, perfect to hide for a little while. A night.

I park the car at the edge of the beach and I begin walking out on the sand. I stopped it, I tell myself, not sure where I am walking. I stopped it. He didn't die. It is low tide. Dawn will be up soon and here on the beach there are scattered pools of water, shallow as a plate. The three streetlights along the beach's edge fret me a shadow three ways around me, so that I look like a walking crowd when I look down. Walking, I see the reflections of stars in the pools, my shadows across them. And I stop at the sight of one shadow that takes a pool of night for a face, two stars where the eyes should be.

Hello, he says.

I say nothing. I want him gone, even as I know, my standing here is the only way he can speak to me.

You know who I am now, don't you, he says.

I do, I say. The two shadows to the side of this one seem suddenly shadow wings, ready to take him away and take me with him. The night turns over us like a stile.

You know who I am now too, I say. So stay.

I wake up the next morning in the charred room of a ruined mansion that burned partly to the ground here in Fort Williams Park some time ago. No one rebuilt it. Supposedly the house is haunted, or cursed. The other houses in the historic neighborhood park, kept empty of residents to preserve them, were locked against me when I tried them, the good people of the town thinking no doubt of someone like me.

There's a blanket over me that I didn't put there. I get up, checking it, and then go to the window.

Bridey sits on the hood of my car, looking off to the sea. He blows on a cup of coffee, squinting. There's a car beside him I don't recognize, looking suspiciously like a rental.

Why did Lady Tammamo take her life instead of living forever? Love ruins monsters. She didn't need the spell of a thousand livers to become human. She just had to love one man. Feel the change come over her: the fur recedes across her brow, the fangs flatten to a smile. The paws turn to feet and say good-bye to flight. The danger of her hides itself in shame. I wrap myself in the blanket and walk down, and then I run down the stairs set in the hill, stopping only when I am in front of him. He doesn't move, just looks at me. It's not the time just yet for questions, not just yet.

Hi, Bridey says.

Hi, I say. Hi.

FOR THEIR EXCELLENT

readings that helped me to shape this novel, thank you to Sarah Sheffield, Shauna Seliy, Patrick Merla, Kirsten Bakis, Emily Barton, Patrick Nolan, Karl Soehnlein, Julie Regan, Sandell Morse, Betty Rogers, Caleb Crain, my brother, Christopher, my sister, Stephanie, and my brother-in-law, Adam Barea. For her unalloyed support for this novel and for her advice, thank you to Hanya Yanagihara. Thank you to Quang Bao, for his support for the novel and his efforts on my behalf. For their beautiful example in persistence, thank you to my mother, Jane Chee, and to my departed father, Choung Tai Chee. For their assistance, without which this book could not have appeared, thank you to Frank Conroy and Connie Brothers, to the Iowa Writers' Workshop and the Michener/Copernicus Society, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, the Asian American Writers' Workshop, and to Donna Brodie and the Writers' Room of New York City. Special thanks to my aunt and uncle, Priscilla and Brian St. Louis, for the use of their barn, and to Katie MacNichol, for her long friendship to me and to this effort. Thank you to my teachers, especially Kit Reed, Annie Dillard, Beatrix Gates, Mary Robison, James Alan McPherson, Marilynne Robinson, Elizabeth Benedict, Denis Johnson, and Deborah Eisenberg. Thank you to Elaine Kim, Tricia Juhn, Mina Park, and all the members of the dinner workshop. Thank you to Rebecca Kurson of Liza Dawson Associates, my agent, and to Chuck Kim, my editor, for having the vision to publish this book. Thanks also to John Weber, Karyn Slutsky, Michele Rubin, Caroline Dennehy, Fritz Metsch, Christian Dierig, and Laura Jorstad, for their excellent work on the novel's behalf. And for my website, thank you to D.J. Paris.

This novel is a work of fiction, invented and imagined. A resemblance of the characters to people living or dead, and to situations from history, if it happens, will be largely a function of a synchronicity between the imagination of the writer and the life of the reader. I would acknowledge there is a boy I did not know, who did set himself on fire in my hometown when I was too young to remember fully, and the faint memory of which haunted me until I wrote this. His story is inviolate, and not here.

The Curse

Â

When it began, it began as an opera would begin, in a palace, at a ball, in an encounter with a stranger who, you discover, has your fate in his hands. He is perhaps a demon or a god in disguise, offering you a chance at either the fulfillment of a dream or a trap for the soul. A comic elementâthe soprano arrives in the wrong dressâand it decides her fate.

The year was 1882. The palace was the Luxembourg Palace; the ball, the Sénat Bal, held at the beginning of autumn. It was still warm, and so the garden was used as well. I was the soprano.

I was Lilliet Berne.

The dress was a Worth creation of pink taffeta and gold silk, three pink flounces that belled out from a bodice embroidered in a pattern of gold wings. A net of gold-ribbon bows covered the skirt and held the flounces up at the hem. The fichu seemed to clasp me from behind as if aliveâhow had I not noticed? At home it had not seemed so garish. I nearly tore it off and threw it to the floor.

I'd paid little attention as I'd dressed that evening, unusual for me, and so I now paused as I entered, for the mirror at the entrance showed to me a woman I knew well, but in a hideous dress. As if it had changed as I'd sat in the carriage, transforming from what I had thought I'd put on into this.

In the light of my apartment I had thought the pink was darker; the gold more bronze; the bows smaller, softer; the effect more Italian. It was not, though, and here in the ancient mirrors of the Luxembourg Palace, under the blazing chandeliers, I saw the truth.

There were a few of us who had our own dressmaker's forms at Worth's for fitting us when we were not in Paris, and I was one, but perhaps he had forgotten me, confused me with someone else or her daughter. It would have been a very beautiful dress, say, for a very young girl from the Loire. Golden hair and rosy cheeks, pink lipped and fair. Come to Paris and I will get you a dress, her Parisian uncle might have said. And then we will go to a ball. It was that sort of dress.

Everything not of the dress was correct. The woman in the mirror was youthful but not a girl, dark hair parted and combed close to the head, figure good, posture straight, and waist slim. My skin had become very pale during the Siege of Paris some years before and never changed back, but this had become chic somehow, and I always tried to be grateful for it.

My carriage had already driven off to wait for me, the next guests arriving. If I called for my driver, the wait to leave would be as long as the wait to arrive, perhaps longer, and I would be there at the entrance, compelled to greet everyone arriving, which would be an agony. A footman by the door saw my hesitation at the mirror and tilted his head toward me, as if to ask after my trouble. I decided the better, quicker escape for now was to enter and hide in the garden until I could leave, and so I only smiled at him and made my way into the hall as he nodded proudly and shouted my name to announce me.

Lilliet Berne, La Générale!

Cheers rang out and all across the room heads turned; the music stopped and then began again, the orchestra now performing the refrain from the Jewel Song aria from

Faust

to honor my recent performances in the role of Marguerite. I looked over to see the director salute to me, bowing deeply before turning back to continue. The crowd began to applaud, and so I paused and curtsied to them even as I hoped to move on out of the circle of their agonizing scrutiny.