Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (19 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

Hitler saw that Goering was serious. He ordered OKW to shelve its plans to attack Sweden, even though he was not at all pleased about it. Hitler toyed with the idea of invading Sweden later in the war, but he never did. So much for the myth of Scandinavian neutrality. Of the four countries in that region, only Sweden escaped the ravages of war, and it was spared only because an obscure German aviator fell in love with a beautiful Swedish woman on a cold winter’s night in 1920.

The invasion of Denmark presented no problems, because it had a land frontier with Germany. It was overrun in a matter of hours by General of Artillery (formerly General of Flyers) Leonhard Kaupisch’s XXXI Army Corps. The invasion of Norway was another matter altogether. Norway had to be overcome by a combination airborne and seaborne invasion under the general direction of Gen. Nikolaus von Falkenhorst’s Group XXI (formerly XXI Army Corps, later redesignated the Army of Norway).

6

Luftwaffe general Hans Geisler’s X Air Corps was assigned to support the invasion. For this task he was given 1,000 aircraft, including 290 He-111s, 40 Ju-87s, 30 Me-109s, 70 Me-110s, 70 reconnaissance and coastal aircraft, and 500 Ju-52 transports.

7

As was the case in Poland, some 340 of the transports were taken from the pilot training schools. The rest of the Ju-52s belonged to Student’s 7th Air, the world’s first parachute division. Geisler’s principal subordinate units were the 4th, 26th, and 30th Bomber Wings and the 1st Special Purposes Bomber Wing (

Kampf -geschwader z.b.V. 1

, or KG z.b.V. 1), a transport unit.

8

The invasions of Norway and Denmark were the first battles in which parachute troops were employed. Unlike in the United States and Great Britain, these troops were members of the air force, not the army. On April 9 they seized Aalborg and Vordingborg in Denmark and Stavanger and Dombas in Norway. But, the planned parachute operation against Oslo had to be cancelled due to bad weather. Oslo fell after a flight of Ju-52s, covered by Me-110s, simply landed at the previously unoccupied Fornebu Airfield and off-loaded an infantry battalion, despite Geisler’s efforts to recall it.

9

The Norwegian campaign seemed all but over on April 10, but it was not. The Royal Navy intervened between April 15 and 19, landing British and French troops at Namsos and Andalsnes and near Narvik, sinking seven German destroyers in the process. Narvik in northern Norway was the main iron ore port and was the key objective of the campaign. It was held by 4,600 men under Lt. Gen. Eduard Dietl, the commander of the 3rd Mountain Division. Dietl’s situation was critical. More than half of his men were sailors (the crews of the sunken destroyers), who had no training in land warfare.

10

Badly outnumbered and cut off by sea, the Luftwaffe supplied Dietl by air while Falkenhorst dealt with the Allied landings and prepared a campaign to relieve Narvik.

Meanwhile, the headquarters of the newly formed 5th Air Fleet took command of the Luftwaffe forces in Norway. Its commander was Erhard Milch. The half-Jewish Nazi wanted his command time, but he did not actually want to leave Germany, the seat of power. He tried to direct operations in Scandinavia from Hamburg, and Hermann Goering actually had to order him to go to Oslo, promising to recall him when the invasion of France began. Milch’s HQ did not begin to move to Norway until April 24. When the invasion of France began three weeks later, Milch returned to Germany (where he received his Knights Cross) and was succeeded by Hans-Juergen Stumpff. General of Flyers Alfred Keller, the former commander of the IV Air Corps, shortly thereafter took command of the 1st Air Fleet in Poland.

11

The Luftwaffe played a decisive role in the conquest of Norway. It attacked the British ground forces and the Royal Navy, forcing them to withdraw from Namsos and Andalsnes, and supported Falkenhorst’s relief expedition to Narvik. After the Allies finally forced Dietl out of the city on May 28, the Ju-52s continued to resupply him. Several of them had to make oneway trips, crash-landing on frozen lakes to bring vital supplies and reinforcements to the trapped mountain troops. A high proportion of the 127 aircraft the Luftwaffe lost in Scandinavia were transports. The Norwegian campaign did not end until June 8, when the British evacuated Narvik and returned home. England needed all of the troops she could muster by that time, because her forces in France had been smashed, and Paris was on the verge of falling to Nazi Germany.

After Halder’s original plan had been compromised by the unlucky majors, a new plan had been proposed by Lt. Gen. Erich von Manstein, the brilliant chief of staff of Rundstedt’s Army Group A. This military genius spotted the decisive weakness in the enemy’s dispositions: their failure to properly cover the Ardennes, a hilly and heavily wooded region which was considered too difficult for armored operations.

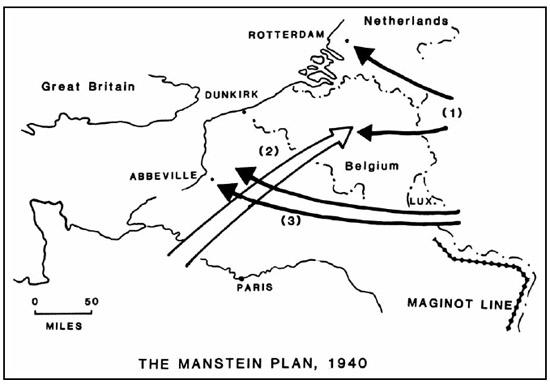

Manstein’s plan consisted of three stages (see Map

4

). First, Fedor von Bock’s Army Group B (Sixth and Eighteenth Armies) would invade the Netherlands and Belgium. Second, the Allies would commit their mobile reserves against Bock, thinking his was the main attack. Third, Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group A would launch the real main attack, spearheaded by Panzer Group Kleist (under General of Cavalry Ewald von Kleist), with half of Germany’s ten panzer divisions, plus three motorized divisions. According to the Manstein Plan, Kleist would quickly drive through the main French defenses on the Meuse River in the vicinity of Sedan before the Allies could react. Then he would drive to the English Channel, cutting off the main French and British forces in Belgium. Meanwhile, to the south, Leeb’s Army Group C would keep the French forces along the Maginot line occupied with diversionary attacks.

The Luftwaffe, as usual, was assigned the task of supporting the armies. Kesselring’s 2nd Air Fleet, consisting of I Air Corps (Ulrich Grauert), IV Air Corps (General Keller), the Air Landing Corps (consisting of the 7th Air and 22nd Air Landing Divisions under General Student), and the 9th Air Division (Lt. Gen. Joachim Coeler), was to support Army Group B. Sperrle’s 3rd Air Fleet, including Loerzer’s II and Greim’s V Air Corps, was to support army groups B and C. As in Poland, most of the Stukas and ground attack aircraft were directed by Baron von Richthofen, now the commander of the VIII Air Corps. This unit was initially attached to the 2nd Air Fleet, but it would be transferred to the south on the third day of the invasion to furnish direct support to the main attack. The II Flak Corps (Maj. Gen. Otto Dessloch) and the I Flak Corps (Gen. Hubert Weise) were assigned to the 2nd and 3rd Air Fleets, respectively, to provide air defense for both ground forces and Luftwaffe installations.

Between them, Kesselring and Sperrle had some 4,000 aircraft, including 1,120 He-111, Do-17, and Ju-88 bombers, 324 Ju-87 Stukas, 42 Hs-123 ground attack biplanes, 1,106 Me-109 fighters, and 248 Me-110 twin-engine fighters, plus about 600 reconnaissance and 500 transport aircraft. They faced 1,151 British, Belgian, French, and Dutch fighters and 1,045 Allied bombers and ground-attack aircraft. They outnumbered their enemy about 2,840 to 2,200 in combat aircraft, excluding 1,200 R.A.F. airplanes still stationed in England for home air defense. Most of these would remain in Britain throughout the campaign. These figures are somewhat misleading, however, because the main French fighters (Curtiss 75A Hawks, Bloch 152s, and Morane-Saulnier 406s) were all inferior to the Me-109 and were fifty to seventy-five miles per hour slower than the Messerschmitt.

12

Also, the commander of the French air force was already thoroughly intimidated by the Luftwaffe.

Map 4: The Manstein Plan. Erich von Manstein’s brilliant plan consisted of three parts: Army Group B attacks the Low Countries (1), drawing in the Allied mobile reserves (2). Then Army Group A delivers the real main attack through the Ardennes (3). The plan worked exactly as planned.

The French commander, Gen. Joseph Vuillemin, was a distinguished World War I ace who was “liked by his soldiers, but whose own ‘ceiling’ was regrettably lower than that to which his planes could ascend in the skies.”

13

In August, 1938, he went on a five-day tour of Luftwaffe installations, where, guided by Milch and that master showman, Udet (who had worked briefly in Hollywood), he was the victim of an elaborate hoax. Visiting airfield after airfield, he saw hundreds of fighters and bombers and was given astonishing (and completely false) production figures. Many of the aircraft Vuillemin saw were the same planes he had seen before: they were being shuttled from airfield to airfield, to deceive him into thinking that the Luftwaffe was much stronger than it actually was. The ruse worked. Vuillemin, thoroughly shaken, reported back to his government that the French air force could not last a week against what he had seen.

The rest of the French leadership was no more astute than Vuillemin, and some were much worse. Gen. Maxime Weygand, the former French chief of staff and still a major influence in the army, said time and time again: “You can’t hold the ground with planes.”

14

Gen. Maurice Gamelin, the French commander-in-chief, shared Weygand’s views. His principal subordinate, Gen. Alphonse-Joseph Georges, commander of the north-east front (extending from Dunkirk to the Swiss border), described the German adoption of panzer tactics as a terrible blunder. “Their tanks will be destroyed in the open country behind our lines if they can penetrate that far, which is doubtful,” he said.

15

Two months before Hitler struck, Georges told General Visconti-Prasca, the Italian military attaché to Paris, that he wanted the Germans to attack, and that he would willingly give Germany a billion francs if they would attack without delay.

16

The Allies did indeed have some significant advantages. They outnumbered the Germans in men and in tanks (by 3,432 to 2,574, excluding obsolete French Renault and British light tanks). Many of the French tanks were superior to the best panzers in firepower and armament, although they were inferior in speed, range, and maneuverability. Unfortunately for the Allies, more than half of the French tanks were scattered among forty infantry support tank battalions, deployed from the English Channel to the Mediterranean Sea.

17

French morale was also very poor. The French had sat in their fortifications for nine months, waiting for German power to collapse by itself. Valuable training time was wasted. Discipline grew lax, suicides occurred with alarming frequency, and alcohol abuse was rampant. They were simply not ready for the offensive when it burst upon them on May 10, 1940.

As was their custom, the Luftwaffe began the campaign with a devastating series of attacks against the enemy air bases. At dawn six wings of He-111s and Do-17s (more than three hundred aircraft) bombed twenty-two airfields in northern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. On the first day of the offensive the Dutch air force was nearly annihilated, the Belgian air force was virtually eliminated, and the French Armée de l’Air was badly stung. The next day R.A.F. bases in France were also smashed. By the evening of May 11, Luftwaffe reports indicated that the Anglo-French forces had lost 1,000 aircraft. By the next day, the R.A.F. and French air units in northern France had lost half their airplanes. This was enough for Vuillemin, who sent most of his units to the interior and dispersed them. As a result, the French air force was scattered everywhere, but had no real strength anywhere. The Luftwaffe was able to gain superiority over them at critical points and times throughout the campaign.

18