Dynamic Characters (24 page)

Read Dynamic Characters Online

Authors: Nancy Kress

You are committing plot.

More on this in the next chapter.

SUMMARY:

YOUR OWN PERSONAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

• A methodical approach to investigating your protagonist can make you aware of aspects of character you may not have thought about.

• The dossier should be used whenever it fits best into your particular writing process—before you begin, after the first draft, somewhere in the middle, etc.

• Think about the dossier questions more completely for your protagonist than for secondary characters, who may not need to be so fully developed.

• Use what you learn about your character(s) to generate plot developments for the novel.

One definition of plot is that it's ''just one damn thing after another.''

Not, however, just

any

damn thing. In fact, in some ways, plot is perhaps the most critical aspect of fiction. ''I want well-plotted stories,'' says the Eminent Editor. (Don't we all?) "What's it about?'' asks Semi-interested Reader, holding a new novel in her hand and meaning "What's the plot about?'' ''But it doesn't have any real plot!'' wails the devoted reader of Charles Dickens upon finishing a story by Grace Paley. Plot, plot, plot. It's enough to make you think we're all conspirators in an endless Machiavellian takeover.

And so we are. We all want—at least vicariously—drama, action, things to happen. But not just any things. Things that catch and hold our interest, which usually means things that have gotten screwed up. Nobody wants to read about things that are humming along in tranquillity. In our lives we want tranquillity; in our fiction we want an unholy mess, preferably getting unholier page by page.

Perhaps the definition of plot in the first paragraph of this chapter should read ''one damned thing after another,'' because events that are damned—that bedevil our characters with physical or mental pitchforks—are what make up plot. That bedeviling is what we're really after when we read fiction. In short, we want conflict.

HOW CHARACTER AFFECTS CONFLICT

Conflict is the place where character and plot intersect. A novel includes several such intersections. Four of the most important are conflict perception, character reaction, conflict resolution, and theme. Let's look at each.

Character Determines What Constitutes a Conflict

Different people—both real-life and fictional—consider different things to be a conflict. I know a man who can make a crisis out of anything: a passing remark, lost keys, a slight fall in the stock market. All of it portends doom and leads to endless confrontations, decisions, drama. I also know another man who is so calm by temperament that for him, nothing less than a death in the family would be considered a crisis. And even that wouldn't be a conflict, but only a grief.

What constitutes a conflict for your character should grow out of what he values, what he struggles for, what matters to him individually. For some characters, leaving home (physically, emotionally) is an immense struggle. Others just pack and go.

What is giving

your

character problems? To answer, you must know who he really is.

Character Determines How Your Protagonist Copes With the Conflict Once He Has It

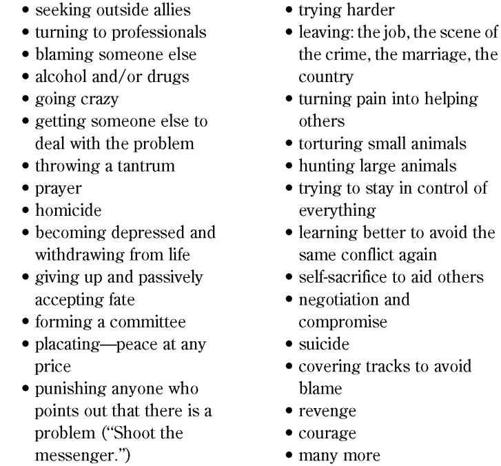

The list of ways human beings meet conflict is endless. It includes:

• denial that there is a • becoming ill with stress problem • relying on hope

• rational problem-solving • creating art

How does your protagonist react to the conflict you've given him? The answer will depend on his individual character. And his reactions will in turn determine plot incidents.

Character Affects, if Not Determines, the Conflict Resolution

Sometimes the resolution, admittedly, is beyond your character's control. Frederick Henry in Ernest Hemingway's

A Farewell to Arms

could not control the fact that Catherine dies in childbirth. Francis Urquhart could not control the fact that he is brought down as Prime Minister of England in Michael Dobbs's novel

To Play the King

(although not in the television version).

In other books, however, the protagonist does resolve the conflict by summoning from within himself aspects of character that he himself may not have known he possessed. Jane Eyre, to take a classic example, refuses to marry Mr. Rochester for reasons of morality (he has a wife living) and self-respect (she will not live with him as less than his equal). This paves the way for Mr. Rochester to become a grieving recluse, who is alone with his mad wife when she sets the mansion afire. He, because of aspects of his character, tries to save her life, and in the process she jumps from the roof and he is blinded. This clears the stage for Jane to return to him. Had she not left in the first place, the book's resolution would have been much different.

Or, consider a more contemporary example: John Grisham's best-selling

The Firm.

Mitch McDeere, the protagonist, is not responsible for the fact that he is in life-and-death conflict with the Mob, the FBI and his employers.

They

have created this situation. But Mitch resolves it by outwitting all three antagonists. He does this by exercising certain aspects of his character: intelligence, daring, ambition and a certain disregard for the law—despite being a lawyer himself.

What aspects of your protagonist's character will affect how the conflict ultimately is resolved?

Character Decides How the Protagonist Feels About the Conflict Resolution

This is actually your story's theme, and so will be more fully discussed in chapter twenty-four. For now, let's look at just a brief, hypothetical example: Two novels are written about a woman's struggle to find love. In both books, she doesn't find it. In the first novel, she ends up defeated and bitter. In the other, she discovers that she is strong enough to stand alone, and even enjoy it. The resolutions are identical, but how the protagonist

feels

about each resolution is not. This means that the first book conveys the message ''Love is destructive.'' The second conveys ''Losing something can show a person positive paths.''

How does your character feel about the plot resolution—based on her individual personality? What does that say about the worldview implied by the book as a whole?

So we're agreed: Character affects plot at several critical places. But how do you actually construct all this? How do you first choose a protagonist? After that, how do you weave conflict and character together? Where do you

start?

Anywhere you can.

GETTING TO CHARACTER FROM ANYWHERE ELSE AT ALL

Let's say you have an interesting idea for a story. Or a setting. Or a character. Or maybe just an intense image. Ursula K. Le Guin began

The Left Hand of Darkness

with no more than that. So did William Faulkner, with

The Sound and the Fury.

Le Guin's image was two figures hauling a sledge across a remote sheet of ice. Faulkner's was a little girl with muddy underpants up in a pear tree.

But now what? How to go from image—or character or setting or idea—to an actual story?

The first step is to turn whatever you have into a character. Fiction (like life) happens to people. So you need questions to ask yourself that will give you a vivid character with many fictional possibilities.

If you're starting from a setting (for more on starting with setting, go back and reread chapter three), ask yourself:

• Who lives here?

• What does she want?

• Why does she want it?

• How hard is this goal to reach? (It should be hard. It may be impossible. The setting should contribute to its difficulties.)

• Who else lives here that might affect the protagonist's pursuit of her goal?

If you're starting from an idea (for instance, ''I want to write a book about the effect of AIDS on a family,'' or, ''I want to write a novel about a terrorist attack on the White House,'' or, ''I want to write a romance about two people working for opposite sides on an oil-spill dispute''), ask yourself:

• Who will be affected by this idea? Make a list.

• Of the people on the list, which ones will be hurt the most? (These people, or their direct advocates, make good protagonists. They have the most at stake.)

• Why is this protagonist involved? What does he want?

• What can go wrong with this idea? (Remember, fiction is about things going wrong.)

• How does this character react to things going wrong with his plans?

If you're starting from an image, ask yourself:

•

Is it an image of a person? If so, who is this person? What is she doing? Why? What is she trying to accomplish? What are her emotions at this particular moment? Why?

• If there's no person in the image (a deserted Aztec pyramid, a jeweled music box that plays a lost Mozart song), who can you put there? Who is interested in this image? Why? What does she want? What is she trying to accomplish? Why?

If you're starting with a character, so much the better. Now ask yourself who this person really is. Use the dossier in chapter fifteen to focus your thinking, if you wish. In fact, no matter where you start, the dossier can be of use in pointing your character creation in directions that may not have occurred to you.