Duke (14 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

• • •

Such services do not come cheap, and Mills was well paid for his labors. The terms of the deal that he struck with Ellington the preceding winter were their secret, but at the end of 1929, Samuel Buzzell, Mills’s lawyer, drew up a certificate of incorporation for Duke Ellington, Inc., that divided ownership of the resulting corporation equally between Ellington, Mills, and Buzzell. After Mills and Ellington had come to a parting of the ways, the

Amsterdam News

reported that the two men had agreed to a 45-45 split of the band’s profits, with the remaining 10 percent going to Buzzell. In 1933

Time

reported that “Mr. Mills’s ‘piece’” of Ellington was 50 percent. Whatever the exact truth of the matter, Mills was in no doubt of what it meant. “I owned the band, you know, he worked for me . . . the band belonged to me and not to him,” he said in 1984. As for the publishing rights to Ellington’s music, Mills’s share was usually larger still, and Louis Metcalf went so far as to claim that “a clause in [the band’s] contract” specified that “every composition that Duke or any of the band wrote had to be sold outright for twenty-five dollars to his manager.”

Today these terms sound close to indentured servitude, but in 1927 it was common for black performers to sign over large chunks of their take to white managers. When Louis Armstrong signed his first management contract in 1929, he agreed to pay Tommy Rockwell $75 out of the first $250 that he earned each week, plus half of any additional net profits, and they split Armstrong’s record royalties evenly. Like Armstrong, Ellington knew that he could not function at the top levels of the music business without a white manager. He also knew that what Mills did for him went beyond mere management. For one thing, Mills relieved him of the day-to-day responsibilities of a businessman, which he would always find tedious. In George Wein’s words, “Duke didn’t want to know, and didn’t want to be bothered. He really did not care about business. He was concerned about music, and the business would take care of itself.” Even more important, though, Mills was starting to construct the public image of the jazzman-as-artist that would define Ellington in the eyes of the media throughout the decade to come. In return he uncomplainingly gave most of his income to Mills.

As his manager-partner explained it:

Duke was a good listener. He followed instructions. He’s sponsored. He’s got nothing to worry about: money, or the job, or the men. Now he can work. All he has to do is write. . . . Duke always knew his position and was always very grateful for everything that was being done, because he knew he was getting all the best of everything. Everything we created [was] “from the pen of Duke Ellington,” whether he wrote it or he didn’t write it.

That last remark goes to the heart of the matter. In order to make Ellington a celebrity, Mills shone a pin-spot of publicity on the band, but it was focused on the leader, leaving his sidemen in the dark. Some of them resented the secondary status to which they were now being relegated. What had started out as a cooperative venture was evolving into an enterprise directed by one man alone. In 1969 Fred Guy complained that Mills “wanted Duke to be the star, not the band. The men were just the rank and file.” No longer was Duke one of the boys: When it came to musical matters, he was the boss, and though he held the reins with the lightest of touches, everyone knew it. Barry Ulanov, who interviewed many of his sidemen in the forties, wrote that Mills’s decision to make him the band’s true leader soon led to “serious disillusionment for the men in the band, a deepening sense of personal and collective tragedy which has never left these brilliant musicians.”

Not all of them felt that way. Sonny Greer, for one, understood and appreciated what Mills was doing: “He was blue-white diamond. He was the guy. He was

the

guy. . . . Everything first class, every time you look around, he said, ‘I better get you guys another set of uniforms.’” Mills poured money into the band without stint, treating it as a long-term investment that would sooner or later pay off in the form of fatter royalties. But in order to make that happen, he first had to make Ellington well-known, and he did so by selling him as an artist:

For me, the development of Duke Ellington’s career was an over-all operation consisting of much more than merely securing engagements for him or selling his songs. Anyone could have done that. My exploitation campaign was aimed at presenting the public [with] a great musician who was making a lasting contribution to American music. I was able to guide Duke Ellington to the top of his field, a field in which he was the first to be accepted as an authentic artist, because I made his importance as an artist the primary consideration.

Still, the engagements had to be secured, and the next step in the selling of Ellington was to find a more suitable showcase for his artistry. That came in December when the band opened at the Cotton Club, the Harlem cabaret where he would perfect the musical style that propelled him, assisted by Mills, to the very top of the tree.

4

“THE UTMOST SIGNIFICANCE”

At the Cotton Club, 1927–1929

I

N 1927 HARLEM

was a playground for white people who could afford to pay for liquor and sex—and who liked having sex with black people, so long as they didn’t have to talk to them afterward. Of the uptown nightclubs that catered to white patrons, the Cotton Club, which billed itself as “the Aristocrat of Harlem” in its newspaper ads, was the best known and most expensive, as well as the one with the dirtiest pedigree. Owney Madden, the owner, was an Englishman of Irish parentage whose family had emigrated to New York’s Hell’s Kitchen when he was eleven years old. He was slight of stature and spoke in a high-pitched voice that sounded, Sonny Greer said, “like a girl.” But appearances were deceiving, for Madden was a vicious street fighter who in his youth had racked up a long list of cold-blooded killings. He now ran one of New York’s most successful bootlegging gangs, investing his profits in Broadway shows like Mae West’s

Sex

(and, it was whispered, having a backstage affair with West herself). In 1920, while he was serving an eight-year term in Sing Sing for manslaughter, he acquired a failed Harlem supper club called the Café de Luxe that had been “owned” by Jack Johnson, the famous black boxer, who served as the front man for yet another mobster. After Madden was paroled in 1923, he turned it into a cabaret with a stiff cover charge whose scantily dressed dancers and sexually suggestive stage shows became the talk of Manhattan.

Located on Lenox Avenue at West 142nd Street, the Cotton Club was a second-story walk-up that held between six and seven hundred people who sat in two tiers of tables surrounding the dance floor. The walls were covered with what Irving Mills, who was prone to malapropisms, called “muriels.” The rest of the décor, as Cab Calloway recalled, was suggestive in a less innocent way:

The bandstand was a replica of a southern mansion, with large white columns and a backdrop painted with weeping willows and slave quarters. The band played on the veranda of the mansion. . . . The waiters were dressed in red tuxedos, like butlers in a southern mansion, and the tables were covered with red-and-white-checked gingham tablecloths. . . . I suppose the idea was to make whites who came to the club feel like they were being catered to and entertained by black slaves.

Spike Hughes, who visited the club a few years later, described it as “expensive and exclusive; it cost you the earth merely to look at the girl who took your hat and coat as you went in.” He was stretching it, but not by much. According to Ellington, the cover charge was “$4–$5, depending on what night it was,” the equivalent of fifty or sixty dollars today. John Hammond remembered the food as being “bad and expensive,” and a menu from 1931 shows that he was at least half right: A sirloin steak cost two dollars. Bootleg champagne (not on the menu) went for $30 a bottle. The prices meant that only well-to-do customers could afford to take the ride that was described in the club’s ads as “15 Minutes in a Taxi Through Central Park” to see “The Best Creole Revue Ever Staged in New York with the Greatest Array of Colored Talent Ever Assembled.”

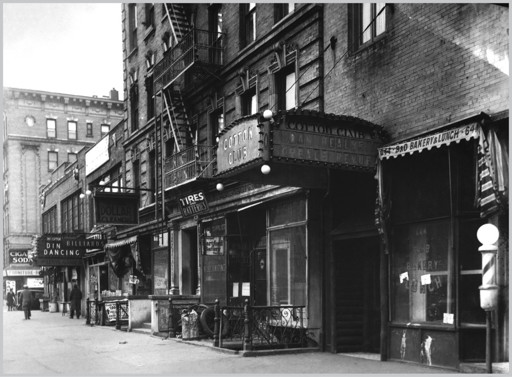

“Expensive and exclusive”: Behind its nondescript façade on Harlem’s Lenox Avenue, the Cotton Club was one of New York’s toniest nightspots, a mobbed-up mecca for moneyed whites who wanted to be amused by black entertainers—including Duke Ellington and his band

Ellington had much to say in

Music Is My Mistress

and elsewhere about the elegance of the club and its clientele:

The Cotton Club was a classy spot. Impeccable behavior was demanded in the room while the show was on. . . . The performers were paid high salaries, and the prices for the customers were high too. They had about twelve dancing girls and eight show girls, and they were all beautiful chicks. They used to dress so well! On Sunday nights, when celebrities filled the joint, they would rush out of the dressing room after the show in all their finery. Every time they went by, the stars and the rich people would be saying, “My, who is that?”

What he took care not to say was that Madden hired only light-skinned women as Cotton Club Girls, and that blacks who sought admission to the club were turned away by the bouncers whom Carl Van Vechten, a white critic and photographer known for his fascination with Harlem and its residents, described as the “brutes at the door.” In July of 1927

The

New York Age,

a black newspaper, warned its readers that the club, by order of the New York Police Department, “does not cater to colored patrons and will not admit them when they come in mixed parties.” The color bar, Spike Hughes said, was not quite absolute: “If you were very famous, like Ethel Waters or Paul Robeson, then the management would allow you to show your coloured face inside the door; but you had to be tucked away discreetly in an inconspicuous corner of the room.” It was, however, strictly enforced whenever racially mixed groups sought admission, so much so that W. C. Handy, the composer of “St. Louis Blues,” was once turned away from a show of his own songs. Connie’s Inn, which opened in 1923, had been the first Harlem cabaret to exclude blacks, but Madden went further: While the shows at Connie’s Inn were written and directed by blacks, the Cotton Club only allowed them to perform onstage.

Ellington’s silence about the awkward fact that he made his name playing in a segregated club in the middle of Harlem is understandable. “Harlem Negroes did not like the Cotton Club and never appreciated its Jim Crow policy in the very heart of their dark community,” Langston Hughes wrote in 1940. Unlike Ellington, Hughes did not find it “classy” that “thousands of whites came to Harlem night after night, thinking the Negroes loved to have them there, and firmly believing that all Harlemites left their houses at sundown to sing and dance in cabarets, because most of the whites saw nothing but the cabarets, not the houses.” But the Cotton Club was a prestigious booking all the same, and Irving Mills, who was never shy about taking credit for other men’s achievements, said that he made it happen. Mills also said that it was his idea for the club to start presenting the Broadway-style stage shows for which it is now remembered, and that he talked George “Big Frenchy” DeMange, the manager, into putting on the club’s first full-scale revue.