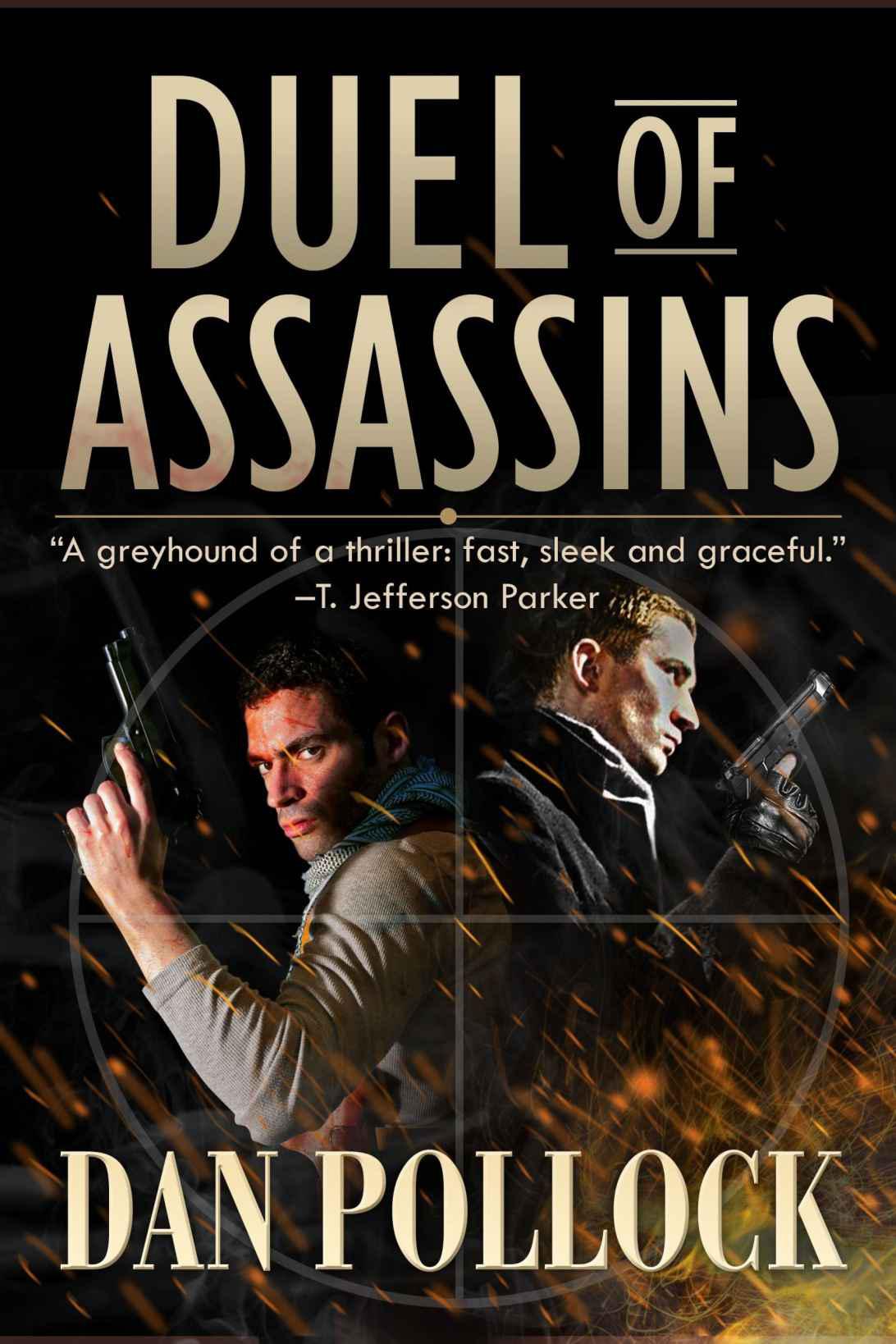

Duel of Assassins

Authors: Dan Pollock

DUEL

of

ASSASSINS

Dan Pollock

Tusitala Press

The

line from the

Hagakure

in chapter ten is quoted from

The Way of the

Samurai

by Yuko Mishima, translated by Kathryn Sparling, copyright © 1977,

Basic Books, Inc., New York

This

book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either

the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any

resemblance to actual eents or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely

coincidental.

Copyright © 1991 and 2014 by Dan Pollock

All rights reserved

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

(from 1992 Pocket

Books edition):

This novel and its writer owe a considerable

debt to the following:

for making it all possible, Angela

Rinaldi;

for making it happen, Jed Mattes and Bill

Grose;

for editorial acumen and persistence,

Dudley Frasier;

for unflagging collegial support, Douglas

Clegg;

for structural insight and tutorial zeal,

James Sewell;

for guidance in Soviet matters, Paul

Goldberg;

and for invaluable technical assistance:

Lt. Col. Harold Barr, USAF (Ret), Kenneth

Goddard,

David and Marie-Luise Pal and Ted

Zahorbenski.

By the same author:

Lair of the Fox / Orinoco / The

Running Boy / Precipice

The author welcomes comments and

questions on his blog:

http://danpollock.blogspot.com

Or email:

[email protected]

For Constance, my darling wife

“The only tough part is the

finding out what you’re good for.”

—Owen Wister,

The Virginian

Lake Lugano, Italy–Spring, 1991

He wasn’t sure whether he was in hiding, or early

retirement. He’d led an active, Odyssean life. Dropout and hitchhiker at

seventeen, carnival roustabout at eighteen, blue-water sailor and international

vagabond at nineteen. Then, by dizzying turns in his twenties, he became a

political defector, special forces commando, assassin and fugitive.

Now, in his mid-thirties, youth’s roller-coaster ride seemed

pretty well over. It had deposited him on a tranquil Alpine lake—a still-young

man with an incredible past and no discernible future. And with nothing to do

on this cloudless morning but guide a slightly-bigger-than-bathtub-size

sailboat across sparkling sapphire water in a sigh of wind.

Or maybe blow his brains out.

Or start all over.

Another possibility was that someone would track him down

and blow his brains out for him, or—more exotically—jab him in the buttocks

with a poison-tripped umbrella.

A final one was that there would come one last summons from

the General. But that possibility was daily diminishing. The General, exiled

and apparently under virtual camp arrest, continued to concoct his grand plans

and promulgate them along his secret network. But the time to act on those

plans was rapidly slipping past. The General was on the point of becoming a

relic, ending up very much as had old Chiang Kai-shek on his tiny island,

shaking a withered fist at the mainland colossus. Events were passing the old

soldier by. The summons must come soon, or not at all.

And if it did not come, the still-young man would have to

think seriously and quickly about turning his hand to something new. Or, more

likely, set about marketing his hard-won lethal skills, since he didn’t fancy

being a hired yachtsman again and couldn’t imagine working indoors.

In harmony with these mental meanderings, he tacked the tiny

boat lazily back and forth across the rippled mirror of Lake Lugano on the

Swiss-Italian frontier. Each swing of the little boom and windslap of miniature

mainsail carried him a bit nearer the spot from which he’d pushed off an hour

before—the steeply terraced, picturebook village of Gandria at the foot of

Monte Brè, five kilometers east of the town of Lugano.

The final tack fetched him perilously near the seawall

windward of his

albergo

, before he rounded dead into the wind, then

backed the main and used the rudder in reverse to drift back slowly under the

corrugated tin roof of the ramshackle quay. The hotdog landing was completely

wasted on a pair of muscular, Nordic-looking girls waiting impatiently to take

the boat out. One of them grabbed the bow line from him as he stepped off.

“Sie kamen dreizehn Minuten zu spät!”

she said,

poking her sportwatch. “You are late thirdeen minutes!”

“Sorry, ladies. Ran into some nasty weather out there.” He

smiled as he trotted past them up the half-dozen steps to the albergo’s

terrace. He settled at an empty table, extending his long, bare legs to a

nearby plastic chair and was presently provided his standard morning

fare—cappuccino, roll and the

International Herlad-Tribune

printed in

Zürich.

Whatever he was doing in Lugano, he really oughtn’t

complain. The morning sunlight was a benediction, the onshore breeze fanned him

attentively, the terrace was bright with flower boxes, and a sparrow on the

railing was eyeing his breakfast cheerfully. The only imperfection was a wet

itch under his bathing suit from sitting too long on a waterlogged boat

cushion.

He folded the newspaper back to the sports pages. Another

baseball season was under way. He hadn’t seen a game in nearly twenty years,

yet it was still comforting to scan the agate-type hieroglyphs of standings and

box scores, old teams with new players, all conjuring the slow summer game.

With less enthusiasm he flipped back to the headlines. The

world had changed so drastically in recent years that his long-ago defection

now seemed almost quaint. The East-West twain and European powers were getting

ready to meet again in mid-July, he saw, at yet another symbolic site—Potsdam,

where the Allies had assembled in ’45 to divide the defeated Germany. The

ongoing wrangle over European realignment was expected to top the agenda, with

everyone scrambling for a piece of the big new pie.

He was skimming the tedious story when the breeze riffled

several pages and his eye was caught by a by-line on an opinion piece.

Charlotte Walsh was a Washington-based columnist specializing in foreign

affairs. She was also an attractive lady whom he’d spotted several times on a

correspondents’ roundup shown on CNN’s European feed. He’d paid special

attention because his contacts told him she was presently sleeping with an old

rival. Small-world department.

She, too, was writring about Potsdam:

WASHINGTON—In

the aftermath of yesterday’s surprise announcement that Potsdam’s Cecilenhof

Palace is going to be dusted off for the next round of multinational summitry,

perhaps a few random observations and speculations may be indulged. One

wonders, for instance, if the Soviet members of the selection committee somehow

prevailed over their North American and Euoprean counterparts. For Soviet

President Alois Rybkin is known to have a certain affinity to style and symbol,

and he might have seen in Potsdam the poosibllity of securing a kind of

historic home-court advantage.

It was, after

all, a Russian leader—albeit a bloody and infamous one—who made the unlikely

choice of the old Prussian capital for the post-World War II conference. And it

was over the Cecilienhof’s red baize table that the Nazi Reich was subsequently

carved up almost precisely along the dotted lines laid down by that leader,

Josef Stalin.

Approaching a

half-century later, that postwar dismemberment has been pretty well sutured

back together. But it will be an equally critical operation that brings the

heads of state together over the table at Potsdam—no less than the redefining

of Europe, and the Soviet place therein.

Naturally,

Rybkin, beleaguered at home and abroad, seeks immediate access to the emergent

colossus, as he has made abundantly clear with his own series of somewhat

amorphous Greater Europe initiatives. To be left out at this critical nexus of

European history could well mean a political death sentence for the Soviet

leader—and, more important, an economic one for his country.

Yet,

ironically compounding his personal dilemma, Rybkin may face political doom

whatever the outcome at Potsdam. For Soviet participation in the expanding

Europe would doubltess entail the relinquishing of a goodly mea-sure of

national sovereignty—a price exacted with varying degrees of predictable

political agony from all signers-on. But the hard-line factions of Mother

Russia, having been dragged kicking and screaming so far down westward paths in

recent years, seem to have dug in their collective heels very deeply over the

issue of sovereignty, and Alois Rybkin well knows it.

Indeed, it

will be a very high-stakes game later this summer at Potsdam, and the canny

Soviet leader will have three-hundred million kibitzers massed close behind

him, second-guessing his every hand—

“Un altro cappuccino, Signore?”

“No, Tino, grazie.”

He put some coins down, folded

the paper and left the terrace. An ornamental but infirm iron staircase led steeply

over an arcaded alleyway to his room, affording a brief view of pastel tiers of

houses stacked skyward like stone and stucco cliff dwellings. Inside his room,

across the tile floor and through the open green-shuttered window, was a

grander vista—the shimmering blue surface of Lake Lugano with Cantine di

Gandria on the shore opposite. But he was momentarily blind to the luminous

beauty. More urgent thoughts were rising rapidly to mind, stimulated by the

paragraphs he’d just read.

If anything was going to force the old General finally to

act against Rybkin, this Potsdam Conference—with its implied threat to Svoiet

autonomy—might just be it.

In that hopeful light, perhaps it was also time to end this

southern sojourn and move north—a little nearer striking distance—to await that

summons. He could stretch his muscles a bit, hone his reflexes, get

reaccustomed to taking physical risks. Even if there was no drumbeat along the

General’s old network, at least he’d be that much readier for free-lance

action.

He crossed the room and threw open a tall pine armoire. On

the top shelf were three hats—a silver motorcycle helmet, the blue beret of the

Soviet special forces, and a black felt cowboy hat.

He reached for the cowboy hat, eased it down over his

thatched blond hair. Then he turned slowly to the dresser-top mirror and

grinned back at the still-youthful gunfighter.