Drink (16 page)

Authors: Iain Gately

Once collected, the aguamiel was placed in clay pots and sealed for a period of four days, during which time it fermented. Pulque brewers were a superstitious lot. They would abstain from sex for the fermentation period, as they believed that intercourse made the brew sour. They also refrained from tasting the pulque, or drinking any other pulque during the brewing period, for the same reason. Anyone breaking abstinence was likely to be cursed with a twisted mouth or possessed by an angry rabbit god. Once pulque was ready, it had to be consumed quickly, as it had a shelf life of little more than twenty-four hours. Fresh pulque has a sweet odor said to be reminiscent of bananas. Off-pulque, however possesses a smell so noxious that, in the words of a Spanish observer, “there are no dead dogs, nor a bomb, that can clear a path so well.” In order to circumvent such perishability, the aguamiel was sometimes boiled down into a syrup, which later could be rediluted and fermented.

The Aztecs appear to have had the strictest drinking laws in history outside Islam. Only men or women over the age of fifty-two could have a draft of pulque whenever and wherever they wished. Most Aztecs died before they were old enough to drink. Illicit drinkers had their hair cut off, their houses demolished, and/or were summarily executed. The Codex Mendoza (1541), a postconquest compilation of native beliefs, features a picture of three young people being stoned to death for drunkenness with a caption explaining that this was no less than they deserved. The old took advantage of their privileges, especially on the festive occasions when they were expected to drink deep. Bernadino de Sahagun, who compiled an account of Aztec civilization before it vanished, gives a touching picture of legal, albeit geriatric, drinkers in their cups: “Once they were all intoxicated they began to sing; some sang and cried, others sang to give pleasure. Each one would sing whatever he liked and in the key he fancied best, and none of them harmonized; some sang out loud, others softly, merely humming to themselves.” The elderly were also issued cigarettes to smoke while they drank, for the combination of alcohol and tobacco was a popular one throughout Central America.

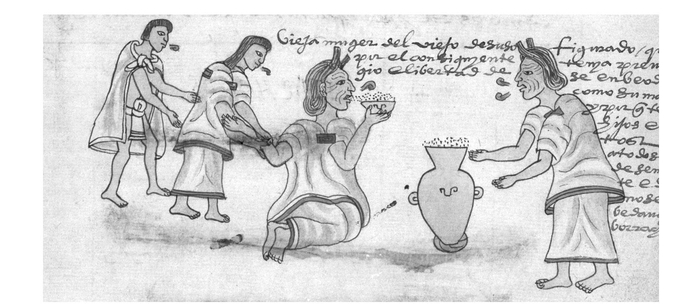

An Aztec matron enjoys the milk of old age.

There were, however, numerous exceptions to such Draconian drinking laws. The nobility of either sex, warriors, pregnant women, pulque brewers and maguey cultivators, and various classes of priests and temple choirs were permitted to drink with differing degrees of freedom. The nobility drank pulque with their meals, as a privilege of their caste, and sometimes mixed it with their chocolate. Warriors and brewers helped themselves from stone troughs at various temples, which were filled to the brim in honor of a number of the denizens of the Aztec pantheon. Moreover, there was one festival at which the entire population, including babes in arms, were required to drink. This was the

Pillahuana

(Drunkenness of Children) festival, held every fourth new year, at which all the children born in the intervening period had their ears pierced and were taken to watch the human sacrifices by their godparents, who acted as chaperones throughout the event and who encouraged, or forced, their charges to drink liberal quantities of pulque. The results, according to a Spanish source, were ugly: “Once drunk, they would quarrel among themselves, they cuffed one another and fell on the floor on top of each other, or else they would go embracing each other.”

Pillahuana

(Drunkenness of Children) festival, held every fourth new year, at which all the children born in the intervening period had their ears pierced and were taken to watch the human sacrifices by their godparents, who acted as chaperones throughout the event and who encouraged, or forced, their charges to drink liberal quantities of pulque. The results, according to a Spanish source, were ugly: “Once drunk, they would quarrel among themselves, they cuffed one another and fell on the floor on top of each other, or else they would go embracing each other.”

In addition to the aforementioned exceptions, some people were cursed by the stars to drink. Rabbit served as an astrological marker—it was one of the signs of the Aztec zodiac, and anyone born on the day of

Umetochtli—2-Rabbit

—was destined to become a drunk, who “would not look for anything else in life save alcohol . . . and only drink it . . . in order to get intoxicated . . . even before breakfast.” Two-Rabbits were easy to spot, as they were notoriously unkempt: “They totter along, falling down and getting full of dust, and red in the face. . . . They do not care, although they may be covered in bruises and wounds from falls, provided they can get drunk, nothing else matters.” Interestingly, the Aztec legal process was unusually sympathetic toward them. Their drunkenness was a valid alibi for any crime. “He has become his rabbit” would be the judgment, and punishment would be left to fate. The defense of possession by one’s rabbit was proof against every charge, though at the price of stigma—people born on luckier days had nothing but “loathing and hatred” for 2-Rabbits.

Umetochtli—2-Rabbit

—was destined to become a drunk, who “would not look for anything else in life save alcohol . . . and only drink it . . . in order to get intoxicated . . . even before breakfast.” Two-Rabbits were easy to spot, as they were notoriously unkempt: “They totter along, falling down and getting full of dust, and red in the face. . . . They do not care, although they may be covered in bruises and wounds from falls, provided they can get drunk, nothing else matters.” Interestingly, the Aztec legal process was unusually sympathetic toward them. Their drunkenness was a valid alibi for any crime. “He has become his rabbit” would be the judgment, and punishment would be left to fate. The defense of possession by one’s rabbit was proof against every charge, though at the price of stigma—people born on luckier days had nothing but “loathing and hatred” for 2-Rabbits.

The Spanish did their best to exterminate Aztec and other New World religious practices and to replace them with Christianity. All the traditional drinking occasions were prohibited, as were the intricate laws governing who might drink and when. This cultural apocalypse resulted in an increase in tippling among their new subjects, to whom it became a secular, as opposed to ritual, pastime. Given the unpleasant living conditions that they were forced to endure after the conquest, it is likely that most of them resorted to alcohol for the purpose identified by Sophocles in classical Greece: to “banish woe.” And while the traditional range of Mesoamerican additives to alcoholic drinks, including tobacco, peyote,

yage,

toad juice, and magic mushrooms, vanished from their brews, the drinks themselves lived on. In Mexico, the Spanish turned pulque into gold. They introduced licensing laws for its production and sale, and taxes on its consumption. A century or so after the conquest, levies on pulque were second only to the silver mines as a source of imperial revenues. They also introduced the technology of distillation, which the Mexicans were quick to adopt. They applied their ingenuity to building stills from the simplest of materials—clay and hollowed-out logs—which they used to extract elixirs from their traditional potations, creating new beverages in the process. Pulque, for example, was transformed into mescal.

yage,

toad juice, and magic mushrooms, vanished from their brews, the drinks themselves lived on. In Mexico, the Spanish turned pulque into gold. They introduced licensing laws for its production and sale, and taxes on its consumption. A century or so after the conquest, levies on pulque were second only to the silver mines as a source of imperial revenues. They also introduced the technology of distillation, which the Mexicans were quick to adopt. They applied their ingenuity to building stills from the simplest of materials—clay and hollowed-out logs—which they used to extract elixirs from their traditional potations, creating new beverages in the process. Pulque, for example, was transformed into mescal.

A similar course of events occurred in Spain’s dominions in South America, which they had subjugated with the same mixture of cunning and brutality as they had employed against the Aztecs. The Incas, their victims in the south, were rulers of an empire encompassing much of modern Peru, Chile, and Ecuador, and parts of Argentina. Their common beverage was maize beer. Its consumption was a vital part of their religious and social rituals. A few drops were offered to the sun god before drinking; and intoxication was encouraged at major ceremonies and feasts, especially those relating to the initiation of children. These last were celebrated by all parents on the second birthday of their first child, when it was given a name, received valuable presents from its relatives, its first haircut, and its last taste of breast milk, and was introduced to alcohol. According to a Spanish source, “As soon as the presentation of gifts was over, the ceremony of drinking began, for without it no entertainment was considered good. They sang and they danced until night, and this festivity continued for three or four days, or more.”

Although the indigenous peoples of South America continued to drink their traditional maize brews postconquest, these were supplemented, as had been the case in Mexico, with distilled spirits, and also with new drinks introduced by the Spanish. The principal novelty was wine. The Spaniards planted the vine in every suitable part of the Americas that they controlled. It flourished best at first in Peru. Although the Spanish government latterly attempted to restrict the trade in South American wine, so as to protect the market for its own exports, by the 1570s Peru was sending its vintages to Chile (which was also a producer), Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, and to the Philippines, to which a transpacific trade route had been opened in 1565.

While the Spanish were building an empire in Central and South America, the Portuguese had concentrated on trading with the Far East. In 1494, after mediation from Pope Alexander VI, the two maritime powers had divided the globe between them along a north-south meridian, with the Spanish allotted all “new” lands west of longitude 39’ 53‘ and the Portuguese the other half of the world. Brazil fell into the Portuguese hemisphere, which they settled and to which they introduced sugarcane and distillation, but their principal efforts were focused on Asia. They established bases in Goa, in India, in 1510, and in Malacca, in Malaysia, the following year, with the intention of cornering the spice trade. In 1536, the Chinese permitted them to use Macau on their coast as a harbor and to purchase the silks and other luxury goods that fetched such colossal prices in Europe. From Macau the Portuguese voyaged to Japan, where they were granted permission to send one ship each year.

Japan had featured large in the European imagination since the publication of Marco Polo’s largely fictional account of the gold-rich island of Zipangu. The gold was a myth, but the actual wealth, power, and sophistication of Japan, and moreover of China, came as a shock to Europeans and increased their fascination with these ancient and complex civilizations. European goods were shoddy in comparison to what China and Japan had to offer, and both places were conscious of their superiority. In consequence, their political organization, their religions, and the personal habits of their populations were scrutinized, with the aim of discovering how commerce could be advanced. As usual, careful attention was paid to their drinking customs.

The universal alcoholic beverage throughout China was rice wine. It had been described by Marco Polo as “a liquor which they brew of rice with a quantity of excellent spice in such fashion that it makes better drink than any other wine.” Moreover, it was “clear and pleasing to the eye. And being very hot stuff, it makes one drunk sooner than any other wine.” The Portuguese found the same substance common in Japan, where it was known as

sake

and was in such demand “that they say that more than one-third of the rice grown in Japan is used in making it.” The rituals with which this popular fluid was drunk were set down in some detail by João Rodrigues, a Portuguese Jesuit who spent several decades in the country, commencing in 1577. His observations reveal some parallels, and some radical differences, with European drinking practices.

sake

and was in such demand “that they say that more than one-third of the rice grown in Japan is used in making it.” The rituals with which this popular fluid was drunk were set down in some detail by João Rodrigues, a Portuguese Jesuit who spent several decades in the country, commencing in 1577. His observations reveal some parallels, and some radical differences, with European drinking practices.

Japanese society was far more formal than that of Europe—the slightest contact between individuals was punctuated by convoluted rituals. As a consequence, their drinking etiquette was correspondingly more complex, especially in the higher echelons of society. Drinking parties and dinner parties were the usual entertainments of the upper classes, each of which was choreographed to the most intricate degree. Their “first and chief courtesy and token of interior love and friendship” was a

sakazuki

—a sake drinking session—at which two or three people drank in turns from the same cup “as a sign of uniting their hearts into one or their . . . souls into one.” Such noble aims were accompanied by tortuous rituals. Stripped to its bones, a sakazuki held for a single distinguished guest, after greetings, a staged entry, an exchange of bows, compliments, and presents, required the host to send a cup of sake to his guest, who was required to return it untasted to the host, who returned it in turn, and so on several times, before the host reluctantly consented to take the first sip.

11

Despite the time such rituals consumed, their participants nonetheless managed to get roaring drunk. To Japanese minds, intoxication was the logical aim of drinking in company, and it was a condition that carried no stigma. Rodrigues contrasted this ethos with Jesuit views of alcohol, which perhaps did not represent those of all his native continent: “In Europe it is a great disgrace to get drunk. But it is esteemed in Japan. When you ask, ‘How is the lord?’ they answer, ‘He is drunk.’”

sakazuki

—a sake drinking session—at which two or three people drank in turns from the same cup “as a sign of uniting their hearts into one or their . . . souls into one.” Such noble aims were accompanied by tortuous rituals. Stripped to its bones, a sakazuki held for a single distinguished guest, after greetings, a staged entry, an exchange of bows, compliments, and presents, required the host to send a cup of sake to his guest, who was required to return it untasted to the host, who returned it in turn, and so on several times, before the host reluctantly consented to take the first sip.

11

Despite the time such rituals consumed, their participants nonetheless managed to get roaring drunk. To Japanese minds, intoxication was the logical aim of drinking in company, and it was a condition that carried no stigma. Rodrigues contrasted this ethos with Jesuit views of alcohol, which perhaps did not represent those of all his native continent: “In Europe it is a great disgrace to get drunk. But it is esteemed in Japan. When you ask, ‘How is the lord?’ they answer, ‘He is drunk.’”

Indeed, at drinking parties and tippling sessions after banquets, it was ill-mannered to stay sober, “and so they are obliged to drink even when it is injurious to their health.” Those who really could not drink had to pretend to be drunk. It was also good form to feign a hangover. This was achieved by sending thank-you letters deliberately late, writ-tenin shaky characters, apologizing for the delay and excusing themselves on the grounds “that from the time they returned home up to the time of writing they had been intoxicated and incapable on account of the amount they had drunk. This is to show how great was the welcome and affection that the host had shown them. It was for his sake that they forced themselves to drink so as to afford him pleasure.”

Despite the differences in ritual, the Japanese shared some opinions with Europeans as to the effect of drinking on the drinker. Like the classical Greeks, they believed alcohol made a person speak his mind. However, and unlike sixteenth-century Europeans, they considered drunkenness de rigueur for business transactions. According to Rodrigues, “They seem to do this on purpose in order to avoid deceit, for the [sake] does not allow any dissembling because it makes them blurt out everything hidden in their hearts and speak their minds without any duplicity.”

Finally, a ceremonial drink was an important part of Japanese death rituals. Before committing

seppuku,

i.e., disemboweling themselves, Japanese suicides would take a farewell draft of sake and provide a cup for the second responsible for beheading them when the pain became too great. The practice was imitated by Christian martyrs (for after an initial welcome the Portuguese were discouraged and persecuted) to gain respect for their faith. A pair of friars martyred in Nagasaki in 1617 “brought wine reserved for mass and poured it into cups and, lifting them up high (for this is the courteous custom of Japan), each gave a cup to his executioner to drink.”

seppuku,

i.e., disemboweling themselves, Japanese suicides would take a farewell draft of sake and provide a cup for the second responsible for beheading them when the pain became too great. The practice was imitated by Christian martyrs (for after an initial welcome the Portuguese were discouraged and persecuted) to gain respect for their faith. A pair of friars martyred in Nagasaki in 1617 “brought wine reserved for mass and poured it into cups and, lifting them up high (for this is the courteous custom of Japan), each gave a cup to his executioner to drink.”

Other books

Fat land : how Americans became the fattest people in the world by Crister, Greg

Watchfires by Louis Auchincloss

Blackmailed Into Bed by Lynda Chance

The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser

Camilla by Madeleine L'engle

Moon's Law (New Moon Wolves 2 ~ Bite of the Moon ~ BBW Romance) by Michelle Fox

The Monster Within by Jeremy Laszlo

The McBain Brief by Ed McBain

Crossings by Danielle Steel

Before the Storm by Sean McMullen