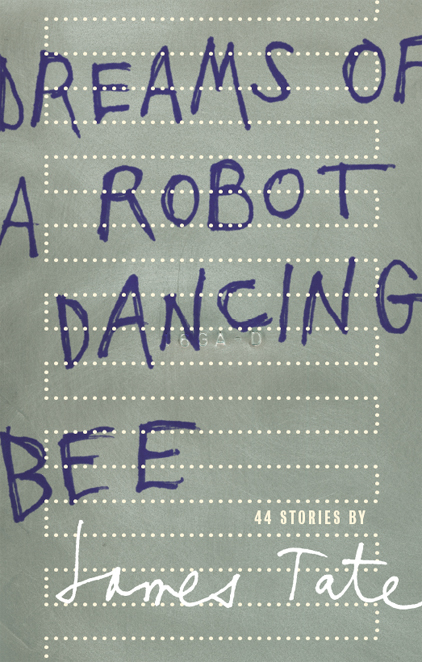

Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee

Read Dreams of a Robot Dancing Bee Online

Authors: James Tate

A ROBOT

DANCING BEE

DREAMS OF

A ROBOT

DANCING BEE

44 STORIES BY

JAMES TATE

Â

WAVE BOOKS

SEATTLE / NEW YORK

THE TORQUE-MASTER OF ADVANCED VIDEO

TRACES OF PLAGUE FOUND NEAR REAGAN RANCH

FAREWELL, I LOVE YOU, AND GOODBYE

A ROBOT

DANCING BEE

THE THISTLE

I

'm sitting there in my den reading an article about the devastating effects of cyberphilia on the contemporary American family, or what's left of it. Cyberphilia, in case you don't know by now, is the compulsion to program and operate a computer, in preference to all other activities (I don't own a computer, I am a cyberphobiac). Anyway, I am still interested in this article, I am gloating away at the verification of my original predictions, when in comes Eileen barking at me: “Paul, would you please get off your duff and go out to the driveway and cut down that damned thistle. If I've asked you once I've asked you a dozen times to cut it down.”

“What's that thistle done to you?” I reply, as I have probably replied at each of her requests all week. I am not allowed to read an article in peace in my study. I have worked for years so that I might be allowed to read an article all the way through to the end on a hot and muggy Saturday afternoon. But no, when Eileen wants a thistle removed from the driveway, then all else must be foresworn and her command obeyed or I will get no peace, the pleasure of reading about the domestic tragedies of the cyberphiliacs has been shattered. Eileen does not take my pleasure very seriously. She doesn't understand my admittedly rather desperate need to be right about

something

. “Eileen,” I said, in one last doomed attempt to defeat the General, “it's not as

though that thistle's going to tear the fender off the car . . . Alright, alright, I'm going . . .”

So I put down my magazine, deprived of even getting to the juicy statistics and a few sample horror stories of children who have not spoken to their parents for years, husbands who have lost all sex drive, etc. The kind of stories that make me feel good about myself, that tell me I was right to never learn what that particular revolution was all about. No, instead I must go out into the sweltering, stifling shed; hunt around among oily rags and hyperactive wasps and hornets for the hedge-clippersâall this so that I can destroy the national emblem of Scotland. But I am by now something of an obedient cur. Oh, it's a well-enough adjusted thralldom I endure.

So I locate the clippers, beneath, as I predicted, the mountain of oily rags, and I am buzzed and tormented by every known species of wasp and hornet, and, since I am allergic to all of their venoms, I am justified in calling this a life-threatening tour of duty. One sting and it's all yours, Eileen: years of National Geographics, all yours, a treasure. The six boxes of travel brochures, all yours. So much rubbish to prove one's been here, been around. And all of it undoubtedly in the dust-bin before my bones have stopped shaking. All the beloved rubbish, inter-changeable with the next guy's. Why the hell not leave well-enough alone, let me go on reading about the smart guy who starved to death in front of his microelectric doo-da. No, no, no, never could it be so.

On Saturdays, Eileen likes nothing better than to issue orders for me to kill things, or be killed:

Those wasp nests on the shutters

,

kill them. The skunk got in the garbage again last night: find him and kill him (or get sprayed by him). Or better yet, get bitten by him, undergo a series of hideous rabies shotsâsince you mortally fear needlesâGet up Paul, put down your beloved magazine, Paul, get out there on the frontline, Paul. Risk your life, Paul. Whatever you do, Paul, don't let yourself get caught in a situation where you might feel comfortable, safe, or even right in one of your predictions

.

So now, here at last, I stand before this stately, decorous

Ono-pordum acanthium

. It is approximately three-and-a-half feet in height and, I regret to report, in magnificent bloom. This is, I realize even more emphatically, a totally senseless execution. I would have preferred she had ordered me to cross the street and cut the throat of the neighbor's dog. Yes, I could have accepted that order since the creature has an apparently incurable tendency to howl at the moon and kept us awake most of last night (most of the past six years is more accurate). But this thistle is a thing of almost breathtaking beauty, given to us by chance, and since Chance seems to be our new God, why am I now ordered to risk incurring the wrath of our newâand, most likely, extremely terrible and cruel when irritatedâGod? Eileen's whim.

Paul, go cut down that thistle by the driveway

. “Why, my dear? Why should I cut down the thistle?”

Because I said so, Paul. Now, do it before I get mad!

It is beginning to rain. As I stand here before this delicate, purple flower with orders to kill, storm clouds are moiling up out of the hills. I can feel the barometric pressure dropping by the minute, and it is beginning to make me feel light-headed. These summer electric storms have been having this effect on me the

past couple of years. I have never actually fainted, but I feel as if I am going to, and it is quite unpleasant. Perhaps I shall faint and never wake up again. Then Eileen would have to do all the murdering herself. Would she feel differently then? Perhaps that would be good for her. After her first bloodshed, say, pouring snail-poison down a mole-hole, and all the little blind star-nosed babies emerge gasping for air, perhaps, she'd give it up and become the patron saint of pests and varmints and thistles.

Now lightning is flashing and there is that deep rumbling that always precedes a real bang-up summer fury. I enjoyed them as a child, felt brave as I comforted my mother, who was terrified out of her mind by lightning. (That's where my child's imagination came up short: I thought it wouldn't strike

me

.) But now, add another entry to my slowly growing list of . . . well, I won't call them phobias, but things-that-fail-to-please-me. At the moment, I feel I may just keel over and be done with it, not have the slain thistle on my list of crimes when I show up at Chanceville.

However, if I make it back to the house and report to the General that her bidding had not been done, she may very well kill me, or at least make certain I never again pick up that magazine and find out just how awful other, more modern people's lives have become. I'll take my chances. I'll tell her it had to stop somewhere, all this killing. And I've taken my stand, finally, with this thistle.

I

was going to cry so I left the room and hid myself. A butterfly had let itself into the house and was breathing all the air fit to breathe. Janis was knitting me a sweater so I wouldn't freeze. Polly had just dismembered her anatomically correct doll. The dog was thinking about last summer, alternately bitter and amused.

I said to myself,

So what have you got to be happy about?

I was in the attic with a 3000 year old Etruscan coin.

At least you didn't wholly reveal yourself

, I said. I didn't have the slightest idea what I meant when I said that. So I repeated it in a slightly revised version:

At least you didn't totally reveal yourself

, I said, still perplexed, but also fascinated. I was arriving at a language that was really my own; that is, it no longer concerned others, it no longer sought common ground. I was cutting the anchor.

Polly walked in without knocking: “There's a package from UPS,” she announced.

“Well, I'm not expecting anything,” I replied.

She stood there frowning. And then, uninvited, she sat down on a little rug. That rug had always been a mystery to me. No one knew where it came from and yet it had always been there. We never talked of moving it or throwing it out. I don't think it had ever been washed. Someone should at least shake it from time to time, expose it to some air.

“You're not even curious,” she said.

“About what?” The coin was burning a hole in my hand. And the rug was beginning to move, imperceptibly, but I was fairly sure it was beginning to move, or at least thinking of moving.

“The package,” she said. “You probably ordered something late at night like you always do and now you've forgotten. It'll be a surprise. I like it when you do that because you always order the most useless things.”

“Your pigtails are starting to crumble,” I said. “Is there anywhere in the world you would rather live?” I inquired. It was a sincere question, the last one I had in stock.

“What's wrong with this?” she replied, and looked around the attic as if we might make do.

“I guess there are shortages everywhere,” I said. “People find ways. I don't know how they do it but they do. Either that or . . .” and I stopped. “Children deserve better,” I said. “But they're always getting by with less. I only pity the rich. They're dying faster than the rest of us.”

When I get in these moods, Polly's the one I don't have to explain myself to, she just glides with me along the bottom, papa sting-ray and his daughter, sad, loving, beautifulâwhatever it is, she just glides with me.

“Are you ever coming down again?” she asked, without petulance or pressure, just a point of information.

“Not until I'm very, very old. I have to get wise before I can come down, and I'm afraid that is going to take a very long time. It will be worth it,” I said, “you'll see.”

“Daddy,” she said, “I think you know something already.”

A

s a rule,” Nona Kuncio was fond of saying, “it doesn't take a Sigmund Freud to understand why a man wants to catch a rainbow trout.” She and her husband Jerry bought the camp four years ago after Jerry's logging accident. Nona kept an eye on all the guests. Most of them she had figured out within a few hours of their arrival. But Jerry liked everyone, even Mr. Lunceford.

When Lunceford registered, Nona knew by instinct the man was not a sportsman. The home address he listed on the slip was a full two-days' drive from there. People came from all over the country, but they came for the fishing. Mr. Lunceford checked-in without so much as a hook and a piece of string. Nona told Jerry: “He looks like some kind of CIA agent trying to pass himself off as a librarian.”

Jerry offered to loan him some of his tackle.

“That's very kind of you, Mr. Kuncio. I may take you up on it, but for now the peace and quiet are all that I need.”

“Just call me Jerry. Lake Umbagog is known all over for its great rainbow fishing. If you change your mind, just let me know.”

Nona told Jerry, partially just to get a rise out of him: “Maybe he's on the lam. You should check the wanted posters when you go to the post office this afternoon.” He was so naive when it came to these things.