Dreaming in Chinese (5 page)

Read Dreaming in Chinese Online

Authors: Deborah Fallows

Tags: #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Translating & Interpreting, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

The Chinese are very superstitious about their language. They consider the number 4 unlucky, like 13 in the West. I couldn’t tell you why 13 is unlucky, but every Chinese can tell you that 4 is unlucky because the word for “four,”

sì , sounds like the word for “die,”

, sounds like the word for “die,”

sǐ . People go to great lengths to avoid using four. There is nary a 4th or 14th or 24th floor in any high-rise building. I always looked for, but only very rarely saw, a license plate or even a telephone number containing the number 4.

. People go to great lengths to avoid using four. There is nary a 4th or 14th or 24th floor in any high-rise building. I always looked for, but only very rarely saw, a license plate or even a telephone number containing the number 4.

Conversely, people pay lots of money to secure a license plate or a phone number with the digit 8, because eight,

bā , rhymes with

, rhymes with

fā

, as in

fā cái

, which means “to become wealthy” in Mandarin. The power of 8 drove the opening of the Beijing Olympics into the rainy season, just so they could begin on the auspicious 08/08/08 at 8:08. (It didn’t rain.)

Similarly, you should never give a clock as a wedding present, because the word for “clock,”

zhōng , sounds the same as the word for “end,”

, sounds the same as the word for “end,”

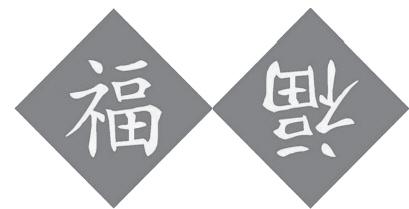

zhōng , which might suggest the end of the relationship. And at Chinese New Year, you should hang the banner with the symbol for

, which might suggest the end of the relationship. And at Chinese New Year, you should hang the banner with the symbol for

fú , or “good fortune,” upside down beside your doorway, because the word

, or “good fortune,” upside down beside your doorway, because the word

dào

means both “to arrive” and “upside down.” Hence hanging good fortune (

fú

) upside down (

upside down (

dào

) also means good fortune (

fú

) will arrive

will arrive

(

dào

) at your doorstep in the coming year. This may seem like a stretch, but the practice is very popular!

Internet punsters are famous for hiding meanings behind their seemingly innocent online postings when they want to avoid being caught by the political censors. One modern fable—which punned as a story about the Communist Party—spread like wildfire across the Internet in early 2009.

Fú

,

“good fortune,” right side up and upside down

On its surface, this concocted “grass-mud horse” fable was innocent enough. It was a story about a horse that lived in the desert, under a threat from invasion of river crabs. But the puns of the words told a very different story, one about the march of Party censorship on the Internet. When net users (called “netizens” in China) read the characters aloud, the puns were obvious, and the meaning of the story became radically different.

Chinese love idioms, proverbs, sayings and morals of the story. They have particular esteem for four-character sayings that sum up a story or fable; others make a historical reference or evoke classics, and others are offered as a nugget of wisdom from everyday life.

Chéngyǔ

, the most classical of the four-character set phrases, are studied in school. They are cherished as linguistic treasures, far more than are their English counterparts, like “the boy who cried wolf” or to “cross the Rubicon” or “a Trojan horse.”

My teacher Danny taught me one:

shǒu zhū dài tù

, which means “sitting by a stump, waiting for a rabbit.” It is really an evocation of a lazy person who waits for a handout instead of working for a living. The backstory is about a guy lazing under a tree one day, when suddenly a rabbit hops along and runs along right into the tree, knocking itself out. “Dinner!” thinks the lazy guy, who goes home to make rabbit stew. He returns the next day, and maybe every day afterward, to sit under the tree and wait expectantly for another rabbit to present itself as dinner, instead of going out trying to earn his own keep.

, which means “sitting by a stump, waiting for a rabbit.” It is really an evocation of a lazy person who waits for a handout instead of working for a living. The backstory is about a guy lazing under a tree one day, when suddenly a rabbit hops along and runs along right into the tree, knocking itself out. “Dinner!” thinks the lazy guy, who goes home to make rabbit stew. He returns the next day, and maybe every day afterward, to sit under the tree and wait expectantly for another rabbit to present itself as dinner, instead of going out trying to earn his own keep.