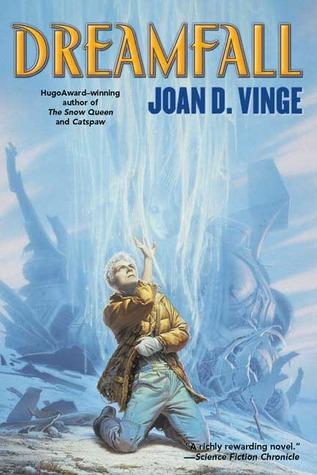

Dreamfall

Cat, Book 3

Joan D. Vinge

1996

ISBN 0-765-30342-6

Spell-checked up to 5. Cleaned up page breaks, most line

breaks, and many typos. Many errors remain.

Praise for Joan D. Vinge’s Cat Novels

Dreamfall

“Vinge displays her potent imagination in the creation of a

world that remains fascinating. She also displays virtuoso quality in her

delving into the emotional torments of her characters, so that one emerges at

the end feeling very satisfied.”

—

Analog

“A powerful book ... Cat (of

Catspaw

and

Psion)

is

back, and he’s as tough and streetwise as ever.”

—

VOYA

“Another well-written SF novel from the Hugo Award-winning

author of

The Snow Queen

Enjoyable and engaging.”

—

The Washington Post Book World

“A tense, lyrical human drama in a complex future setting.

Vinge has created a world that is exotic and, more important, believable. Her

characters come alive through masterly writing.”

—

Ontario Whig-Standard

Catspaw

“A rich tale of palace intrigue that is both crisp and

captivating.

Catspaw

also comes with enough plot twists to keep you on

edge.”

—

Providence Journal

Psion

“Ambitious, effective science fiction adventure.”

—

Booklist

Books by Joan D. Vinge

The Snow Queen Cycle

The Snow Queen

World’s End

The Summer Queen

Tangled Up in Blue

The Cat Novels

Psion

Catspaw

Dreamfall

Heaven Chronicles

Phoenix in the Ashes

(story collection)

Eyes of Amber

(story collection)

The Random House Book of Greek Myths

To

Dr. Frederick

Brodsla

Dr. Anna Marie Windsor

Dr. Richard Reindollar

“We arrive at truth, not by reason only, but also by the

heart.”

—Pascal

I would like to acknowledge the invaluable input and support

of the following people, without whom neither this book nor my life in general

would be in such good shape right now—Jim Frenkel, Barbara Luedtke, Carroll

Martin, Betsy Mitchell, the Peach-Poznik clan, Mary and Nick Pendergrass, and

Vernor Vinge. Thanks, guys—you’re the best.

“What’s th’ goal of th’ game, Mr. Toad? A

monster

slain?

A

maiden

saved? A

wrong

righted?”

“A standoff achieved.”

—Bill Griffin

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly, for you tread on my dreams.

—W. B. Yeats

The road to Hell is paved with good intentions.

—Karl Marx

Five or six centuries ago, the Prespace philosopher Karl

Marx said the road to Hell is paved with good intentions. Marx understood what

it meant to be human ... to be flawed.

Marx thought he also understood how to end an eternity of

human suffering and injustice:

Share whatever you could, keep only what you

needed.

He never understood why the rest of humanity couldn’t see the

answer, when it was so obvious to him.

The truth was that they couldn’t even see the problem.

Marx also said that the only antidote to mental suffering is

physical pain.

But he never said that time flies when you’re having fun.

I glanced at my databand, checking for the hundredth time to

see whether an hour had passed yet. It hadn’t. This was the fifth time in less

than an hour that I’d found myself standing at the Aerie’s high parabolic

windows, looking out at a world called Refuge; escaping from the noise and

pressure of the Tau reception going on behind me.

Refuge from what

?

For who

?

The background data the team had been given access to didn’t

say.

Not from Tau’s bureaucracy. Not for us.

The research

team I was a part of had arrived at Firstfall less than a day ago. We hadn’t

even been onworld long enough to adjust to local planetary time. But almost

before we’d dropped our bags here in Riverton, Tau Biotech’s liaison had

arrived at our hotel and forced us to attend this reception, which seemed to be

taking place in stasis.

I dug another camph out of the silk-smooth pocket of my

bought-on-the-fly formal shirt, and stuck it into my mouth. It began to

dissolve, numbing my tongue as I looked out again through the Aerie’s

heartstopping arc of window toward the distant cloud-reefs. The sun was setting

now behind the reefs, limning their karst topography of ragged peaks and

steep-walled valleys. A strand of river cut a fiery path through the maze of

canyons, the way it must have done for centuries, transforming the landscape

into something as surreal as a dream.

Below me, the same river that had turned the distant reefs

into fantastic sculpture fell silently, endlessly over a cliff. Protz, Tau’s

liaison, had called this the Great Falls. Watching the sluggish, silt-heavy

waterflow, I wondered whether that was a joke.

“Cat!”

Someone called my name. I turned, glancing down as I did because

some part of me was always afraid that the next time I looked down at myself I’d

be naked.

I wasn’t naked. I was still wearing the neat, conservatively

cut clothes I’d overpaid for in a hotel shop, so that I could pass for Human

this evening. Human with a capital H. That was how they said it around here,

not to confuse it with Hydran:

Alien.

An entire city full of Hydrans lived just across the river.

There were three of them here at this reception tonight. I’d watched them come

in only minutes ago. They hadn’t teleported, materializing unnervingly in the

middle of the crowd. They’d walked into the room, like any other guest. I

wondered if they’d had any choice about that.

Their arrival had crashed every coherent thought in my mind.

I’d been watching them without seeming to ever since, making sure they weren’t

watching me or moving toward me. I’d watched them until I had to turn away to

the windows just so that I could breathe.

Passing for human

.

That was what they were

trying to do at this party, even though they’d always be aliens, their psionic

Gift marking them as freaks. This had been their world, once, until humans had

come and taken it away from them. Now they were the strangers, the outsiders;

hated by the people who’d destroyed them, because it was human to hate the ones

you’d injured.

The butt end of the camph I’d been sucking on dissolved into

bitter pulp in my mouth without doing anything to ease my nerves. I swallowed

it and took another one out of my pocket. I was already wearing trank patches;

I’d already drunk too many of the drinks that seemed to appear every time I

turned around. I couldn’t afford to keep doing that. Not while I was trying to

pass for human, when my face would never really pass, any more than those alien

faces across the room would.

“Cat!” Protz called my name again, giving it the querulous

twist it always seemed to get from someone who didn’t believe they’d heard all

there was to it.

I could tell by the look on his face that he was coming to

herd me back into the action. I could see by the way he moved that he was

beginning to resent how I kept sliding out of it. I took the camph out of my

mouth and dropped it on the floor.

As he forced me back into the crowd’s eye I looked for somebody

I knew, any member of the research team I’d arrived with. I thought I saw

Pedrotty, our bitmapper, on the far side of the room; didn’t see anyone else I

recognized. I moved on, muttering polite stupidities to one stranger after

another.

Protz, my keeper, was a midlevel bureaucrat of Tau Biotech.

His name could have been anything, he could have been any of the other combine

vips I’d met. They came in both sexes and any color you wanted, but they all

seemed to be the same person. Protz wore his regulation night-blue suit and

silver drape, Tau’s colors, like he’d been born to them.

Probably he had. fn this universe you didn’t just work for a

combine, you lived for it.

Keiretsu,

they called it: the corporate

family. It was a Prespace term that had followed the multinationals as they

became multiplanetary and finally interstellar. It would survive as long as the

combines did, because it so perfectly described how they stole your soul.

The combine that employed you wasn’t just your career, it

was your heritage, your motherland, existing through both space and time. When

you were born into a combine you became a cell in the nervous system of a

megabeing. If you were lucky and kept your nose clean, you stayed a part of it

until you died. Maybe longer.

I looked down. The fingers of my right hand were covering

the databand I wore on my left wrist—proving my reality, again.

Without a databand you didn’t exist, in this universe. Until

a few years &go, I hadn’t had one.

For seventeen years the only ID I’d worn had been scars.

Scars from beatings, scars from blades. I’d had a crooked, half-useless thumb

for years, because it had healed untreated after I’d picked the wrong mark’s

pocket one night. The databand I wore now covered the scar on my wrist where a

contract laborer’s bond tag had been fused to my flesh. I had a lot of scars.

The worst ones didn’t show.

After a lifetime on the streets of a human refuse dump

called Oldcity, my luck had finally changed. And one of the hard truths I’d

learned since then was that not being invisible anymore meant that everybody

got to see you naked.

“You’ve met Gentleman Kensoe, who heads our Board ....”

Protz nodded at Kensoe, the ultimate boss of Tau, the top of its food chain. He

looked like he’d never missed a meal, or a chance to spit into an outstretched

hand. ‘And this is Lady Gyotis Binta, representing the Ruling Board of Draco.”

Protz pushed me into someone else’s personal space. “She’s interested in your

work—”

I felt my mind go blank again. Draco existed on a whole separate

level of influence and power. They

owned

Tau. They controlled the

resource rights to this entire planet and parts of a hundred others. They were

the ultimate keiretsu: Tau Biotech was just one more client state of the Draco

cartel, one of a hundred exploiting fingers Draco had stuck into a hundred

separate profit pies. The Draco Family, they liked to call it. Cartel members

traded goods and services with each other, provided support against hostile

takeover attempts, looked out for each other’s interests—like family. Keiretsu

also meant “trust”.... And right now Draco didn’t trust Tau.

Tau’s Ruling Board had drawn the unwanted attention of the

Federation Trade Authority. Cartels were autonomous entities, but most of them

used indentured workers from the

1i11\

’s Contract Labor

pool to do the scut work their own citizens wouldn’t touch.

Technically, the Feds only interceded when they had evidence

that the universal rights of their laborers were being violated. The FTA

controlled interstellar shipping, and no combine really wanted to face FTA

sanctions. But I knew from personal experience that the way bondies were

treated wasn’t the real issue for the Feds. The real issue was power.

The FTA was always looking for new leverage in its endless

balance-game with the combines. Politics was war; the weapons were just better

concealed.

I didn’t know who had reported Tau to the Feds; maybe some

corporate rival. I did know the xenoarchaeology research team that I’d joined

was one of Tau’s reform showpieces, intended to demonstrate Tau’s enlightened

governmental process. We’d come here at Tau’s expense to study a living

artifact called the cloud-whales and the reefs of bizarre detritus they had

deposited planetwide. The Tau Board was sparing no expense to show the Feds

they weren’t dirty, or at least were cleaning up their act. Which was a joke,

from what I knew about combine politics, but not a funny one.

It was just as obvious that Protz wanted—expected—everyone

on the team to help Tau prove its point.

Say something,

his eyes begged me,

the way I knew his mind would have been begging me if I could have read his

thoughts.

I looked away, searching the crowd for Hydrans. I didn’t

find any. I looked back. “Good to meet you,” I muttered, and forced myself to

remember that I’d met Board members before. I’d been bodyguard to a Lady; knew,

if I knew anything, that the only real difference between a combine vip and an

Oldcity street punk was what kind of people believed the lies they told.