Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (57 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

With this session, too, Hugo and Luigi seem to have come to a new appreciation of their artist. Part of that appreciation may have been a result of their seeing him work the Town Hill Club in Brooklyn the week before. It was, said Luigi, “an experience to live through, to see Sam singing to a black audience. He just stood there, he hardly moved, a little bit of sweat on his forehead, but it seemed like it was effortless, the audience just loved every nuance, they fed on every little thing, they were enwrapt.” That, said Luigi with a certain degree of self-amusement, was what finally convinced them they had the right guy. “We went backstage afterward and said, ‘You were singing real good.’ And he said, ‘Oh, man, I was just shuckin’.’ You know, he threw it off. But we were just floored by what he could do with an audience.”

Clyde McPhatter, Hank Ballard, Lloyd Price, Freddie Pride, Sam, Dee Clark, ca. 1960.

Courtesy of Billy Davis

The Henry Wynn Southern swing started the weekend after the session, playing Birmingham on Easter Sunday. The featured acts in addition to Sam were Dee Clark, Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, the Drifters, blues singer Big Maybelle, Motown Records founder Berry Gordy’s latest success story, Barrett Strong (Gordy had also cowritten Strong’s current hit, “Money”), along with the Hank Moore Orchestra. There were lots of girls, lots of parties, and Sam enjoyed hanging out once again with Midnighters’ guitarist Billy Davis and various individual Drifters. But inevitably much of the talk was of Jesse Belvin’s death three months earlier in an automobile crash that had taken the lives of his guitarist, his driver, and his wife as well and directly raised the question: just how dangerous was this new racial climate getting to be?

Belvin had been killed when the tires on his 1959 Cadillac blew out following a show with Jackie Wilson and Arthur Prysock in Little Rock, Arkansas. It was the same old ugly peckerwood story. The show was booked to play a segregated dance, and when Jackie refused to do a second show for whites, after a “hot dispute with [the] dance managers,” the

Los Angeles Sentinel

reported, “Wilson and his group were allegedly ordered out of town at gunpoint.

“Investigators believed,” the story went on, “that . . . disgruntled [white] dance fans were responsible” for slashing Belvin’s tires, a conclusion bolstered by the rumor that both Jackie and Prysock also suffered tire problems as they drove to the next date in Dallas. Although nothing was ever conclusively proved, there was little doubt about culpability among Belvin’s fellow performers (“Did Racism Kill Jesse?” was the headline in the

Norfolk Journal and Guide

), and it could only have served as a sobering reminder of the dangers that each of them faced almost daily. Like it or not, they were being drawn into a conflict they could scarcely avoid. As they headed through the Carolinas, they saw the spreading sit-in movement and the implacable white resistance to it. Increasingly there was no hiding place, and even entertainers who in less perilous times might simply have clung to their conventional role as good-will ambassadors for the music were induced to speak out. “They try to knock us down,” said the normally phlegmatic Count Basie of the sit-ins, “but we get right up again.” It was, he said, a “beautiful” movement.

By the time they got to New Orleans on April 27, Sam and Clif were thoroughly dissatisfied with the drummer for the Hank Moore Orchestra. Sam was eating at Dookey Chase’s Restaurant on Orleans Street and freely expressing his unhappiness when local bandleader Joe Jones overheard the conversation and suggested to nineteen-year-old drummer Leo Morris that he introduce himself to Sam. Morris, who came from a family of drummers and had grown up playing percussion for his “play-cousins,” the Neville brothers, did just as Jones suggested. “So I introduce myself, and he’s talking and eating, and he said, ‘Man, do you know any of my songs?’ I said, ‘Yeah,’ and he started singing, and I started playing on his dinner table, and he hired me! I knew all his songs, and that night, I just walked on, asked the drummer to get up, put my snare drum down, and played the show. The next day I left town with him.”

They went straight from there into the Apollo. Leo Morris had never been to New York before, and, according to Charles, he spent most of his time looking up. “Charlie was my mentor. He was showing me the ropes, man. I didn’t drink, and I didn’t gamble, but he showed me all the ropes. He used to call me Little Brother, said, ‘Little Brother, now look, when you get there, this is what you do.’ And he would tell me different things. He said, ‘We’re going to New York, New York. The town is so hip they named it twice!’ He would take care of Sam, and then him and I would go hang out. It just was Clif [I had problems with]. I think Clif was kind of disappointed that Sam had hired this guy and I could walk right up and play Sam’s show without any rehearsal. He would try to tell me about, ‘The arrangement go like this,’ and this and that. And Sam would say, ‘Oh, fuck it, man, whatever he doing is good, man.’ I think that was kind of a shock for Clif, that I was that good and Sam liked me that much.”

For Leo it was a lesson in music and in life. “Sam was so soulful, you could follow him [musically] wherever he went. He had a way of singing, it was like Mahalia Jackson, she could sing a Christmas carol, and people would cry. And Sam had that same communication line. He could sing to an audience, and he would have their complete [attention]—I would look down the rows from the stage, and everybody would be looking at him, man, they couldn’t take their eyes off him.”

They played weeklong runs at the Howard in Washington, the Royal in Baltimore, the Tivoli in Chicago, “and everywhere we went, they had to pull him offstage, because the people [wouldn’t let him go] until he’d come out and just sing a few more notes. In those theaters they show a movie and a newsreel and a cartoon, but they usually had to cut some of the newsreel or the cartoon because the show was always running over. He was a wonderful guy to be on the road with, because everything went so smooth. I had a daughter—I got married at eighteen when my girlfriend got pregnant and I didn’t really know too much about how to maintain a family, but Sam would always tell me, ‘Man, you’re lucky you’re married. You got a daughter, and you got a family.’” Leo’s impression was that Sam would like to have a family, too. Sam talked to him all the time about how much he would like to have a son. But Leo was unaware that Sam was even married (“Because, you know, the ladies was there every night, you had to beat them off of him”), let alone that his wife was pregnant with their second child.

Barbara was, in fact, almost five months pregnant but not anywhere near as far along in her marriage as she had believed she would be by now. Some of Sam’s friends, she knew, thought that with another child she was just trying to tie him up in a trick bag, and it had certainly occurred to her that if she could provide him with the son and heir he so desperately wanted, he was unlikely to ever leave her again. But she had other plans to make herself indispensable in his life. At Sam’s suggestion she was familiarizing herself with his business, she had read books and articles that he and Alex recommended and learned some of the language that the attorneys spoke. She spent time with his manager and his manager’s wife, too. She knew they looked down on her for her lack of education, and perhaps for that reason, she didn’t always present herself to them in the best way. Sometimes she got a little too “relaxed” in preparation for going to see them and their highfalutin friends, and she was well aware that, lacking Sam’s gift for bullshit and charm even when he didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about, she could get lost in the conversation and make a fool of herself. But she was determined to stay close to Jess, because Jess was taking Sam places, and this time she was not going to get left behind.

So far as his so-called friends and family were concerned, she generally kept her distance. She knew they would cut her out in a minute—they were all out for themselves, Sam seemed to attract hangers-on like flies. But if she wanted to be able to give Sam the advice he needed, she had to maintain her objectivity, she couldn’t get all caught up in the gossip and in-fighting that was bound to go on with all these weak-minded motherfuckers. Sam didn’t seem to understand that he had to get rid of the deadwood, he needed to learn to take care of business, and if their marriage was going to have any kind of meaning, he needed to understand that she was the one person who could help him to achieve that goal.

S

AM ARRIVED IN CHICAGO

on May 20 for a weeklong engagement at the Tivoli Theater, and, as usual, it was nothing but a party. Sam’s whole family, and most of the old neighborhood, showed up, the liquor was flowing backstage, and women were practically falling out of his dressing room. The Flamingos, a Chicago-based quintet founded by four Black Jews whose harmonies were distinctly influenced by the Jewish minor-key tradition, were the second act on the bill. Their latest record was Sam’s song, “Nobody Loves Me Like You,” the number J.W. had pitched to them the previous spring and Kags’ first big independent hit. Jess came to town, too, and once again felt challenged by his client for reasons he didn’t altogether understand.

“I thought Sam would be staying with his parents or at some decent hotel, so I made reservations for myself at the Congress, but Sam said, ‘Cancel that. I got a room for you where I’m staying.’ So we get in a cab to the South Side and get to this four-story hotel with a big lobby and just a couple of chairs and a television set in it and—‘Hey, Sam, how are you?’ He knew the guy behind the desk, and it seemed like here’s his whole neighborhood waiting for him. Sam says to me, ‘Get your key.’ No one took your luggage, no one showed you to your room. So I go over to the desk and say, ‘Can I register?’ and the guy says, ‘What’s your name?’ I told him and said, ‘Cooke says I have a reservation.’ He says, ‘Yeah, we got a room for you, let me have a dollar deposit.’ I said, ‘Deposit?’ And now I’m watching other people check in who are with us, and they’re not asking them for a dollar. The beds upstairs were these old spring-type beds, but [Sam’s] attitude was, ‘I stay here, you stay here.’”

It was, Jess felt, as if Sam were constantly testing him, racially, politically, financially (“He made me sweat out my commission check sometimes; he let me know he was out there working, and I was back in L.A.”)—but he tried to shrug it off, recognizing that Sam had legitimate reasons for his anger and willing, for the time being at least, to bear some of the brunt.

What he wasn’t willing to do was to indulge Sam in extended conversations about his so-called business interests. From his perspective, the business was a joke, and Alexander was just draining off the money that Sam made from his writing and performing to build up his half-ass label. J.W. for his part saw Jess as an ill-tempered snob, someone who could get Sam through doors that he and Sam could never go through on their own but to whom you never revealed your true thinking because he always had some smart-ass white man’s logic to dismiss it with.

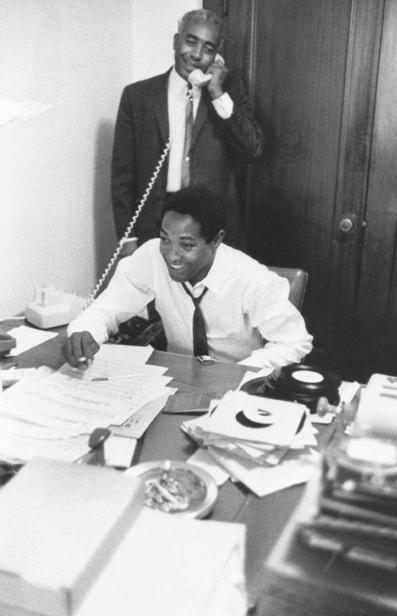

Doing business at SAR: Sam and Alex.

Courtesy of Carol Ann Woods

Johnnie Morisette’s first SAR single came out at the beginning of May and was immediately designated a

Billboard

pick. L.C.’s manager, the disc jockey Magnificent Montague, jumped on the record in Chicago, and it was a turntable hit in several other cities, where good will was able to generate significant airplay. So, even if it didn’t sell that many copies, it definitely put SAR on the map. And it encouraged J.W. to take professional office space in the Warner Building at 6425 Hollywood Boulevard, just ten feet by fifteen feet with barely enough room for two desks, a file cabinet, a phonograph, and a tape recorder but directly across the hall from Lew Chudd’s Imperial Records, home of Fats Domino, Ricky Nelson, and Slim Whitman. (“Being on a major boulevard,” wrote Sam and J.W.’s idiosyncratic consigliere Walter Hurst, “made this a good address, and the building had sufficient turnover [so that should the company want to expand] they would be able to find appropriate offices in the same building.”) On the door a sign grandly announced KAGS MUSIC CORP, SAR RECORDS INC, MALLOY MUSIC CORP (a secondary publishing arm of the business), but inside, it was just J.W. working the phone—unless he was on the road personally promoting a record.