Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke (42 page)

Read Dream boogie: the triumph of Sam Cooke Online

Authors: Peter Guralnick

Tags: #African American sound recording executives and producers, #Soul musicians - United States, #Soul & R 'n B, #Composers & Musicians, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #BIO004000, #United States, #Music, #Soul musicians, #Cooke; Sam, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Cultural Heritage, #Biography

Only the Biggest Show of Stars soldiered on, completing a western segment that included Saskatchewan and British Columbia, then swinging back through Texas and Oklahoma until it reached the Southeast once again, where, fifty-six days after its start, the tour returned to Norfolk for what the

Norfolk Journal and Guide

anticipated would be another keen “battle of songs” between Sam, a “newcomer to the million-sales record field, and Clyde McPhatter, an old pro, [who] have clashed in wars of words and music . . . everywhere the show has appeared to date.”

In addition to the stories in

Tan

and

Sepia,

there were features on Sam in the teen magazines

Song Hits, Hit Parader,

and

Rhythm and Blues.

There was some concern on Sam’s and Bumps’ part that they had yet to come up with a suitable follow-up to “You Send Me,” which had now sold nearly two million copies and, in something of an historic first, actually managed to launch a label with a number-one hit. But the album was selling well enough to bear out Bumps’ strategy of musical diversification, and Sam’s signature hit had entered the national consciousness to such an extent that its very paucity of lyrics had become a frequent object of good-natured satire. Prophet John the Conqueror, a Chicago freelance preacher/promoter Sam had known since his QC days, confidently predicted that Sam’s next three recordings, “regardless of the type or title, [would] sell a million or more copies.” None of it seemed to touch Sam anyway. Irrespective of record sales or the Copa debacle, said Lou Adler, who saw the Biggest Show of ’58 on the Coast, “Sam just seemed to be comfortable within himself. I mean, the excitement backstage with all those performers was unbelievable, but it all changed when he walked in. This was a guy that was different from everyone [else] who was in the room.”

K

EEN RECORDS

by all appearances was thriving. Bumps had by now built up a full-fledged roster, with the Valiants, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, and J.W. Alexander’s Pilgrim Travelers, who, as the Travelers, had just put out their first two pop releases, including “Teenage Machine Age.” Bumps had developed a gospel line, too, with strong new releases by the Gospel Harmonettes and the Five Blind Boys of Alabama as well as the Pilgrim Travelers, all former Specialty artists. There were in addition a host of newcomers, with artists like Marti Barris, Milton Grayson, and a young group from the Greek community, the Salmas Brothers, all showing varying degrees of commercial promise.

John Siamas spent more time at the record company now than at his aircraft parts business, mostly because, as his teenage son oberved, “he enjoyed it more. There were other executives at Randall to run operational matters, but this was his avocation.” As a longtime sound buff, he had planned from the start “to develop a high-quality recording studio,” and to that end he had recruited a Greek-American engineer, Dino Lappas, who had designed it and was building it for him at the label’s new West Third Street location.

Lou Adler and Herb Alpert had long since graduated from their assistants’ roles; they were now not only writing and producing for pretty, blond Marti Barris, they had written and produced Sam’s latest single, “All of My Life,” which unfortunately turned out to be his first not even to chart. They had at this point learned all there was to learn from Bumps, but they were still in the process of seeking an answer to the question that bedeviled everyone who went to work at Keen: “Where’s Bumps?!”

“Bumps was a teacher,” Lou said, expressing a sentiment on which both he and Herb were in full agreement. “His strength was [as] an educator—and he wanted you to learn. [When we first started], he’d give us a stack of tapes and acetates, and he’d have us break ’em down by verse and by chorus. And then he would grade us, just like school. ‘That was good. You picked the right verse. You picked the right song.’ He pretty much taught us song structure.”

His downfall, unfortunately, was organization. “After he hired us, we spent the next three months trying to find him. He’d say, ‘Meet me here.’ We’d go there, and they’d say, ‘He just left.’ We knew Bumps was scattered, everyone knew that Bumps would make an appointment and not show up, not follow up on something he should have taken care of—that was just Bumps. He never felt professional, even to us. He felt

great,

he felt like he’d do anything for you, stay up twenty-four hours a day, he was always thrilled about [any] event that elevated things and took them to another level, levels he had probably dreamed about. But they were beyond him—the monetary thing for Bumps was secondary, but he always sort of outhustled himself, [he always] reached his level of incompetence.”

Follow a&r apprentice Freddy Smith felt much the same way, only more so. Freddy was trying to pitch a song that he and his new songwriting partner, Cliff Goldsmith, had written. It was called “Western Movies,” a kind of cowboy comic opera along the lines of a Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller-produced Coasters record, and every time he sang and played it for Sam on the piano, Fred said, “Sam would roll on the floor, laughing like nobody’s business. He says, ‘Bumps, you gotta do it, man. You gotta do it.’ But Bumps kept procrastinating, and Cliff, my partner, is dying, ’cause I can’t get nothing done.”

The way Freddy saw it, it was symptomatic of the way Bumps took care of business—or didn’t. “Bumps had no organization.

None.

And all these people scattered out everywhere with promises that he’s going to do things and stuff. My thoughts of Bumps was, I learned the business by watching his mistakes. As far as I’m concerned, Bumps should have paid [more] attention.”

But Bumps was paying attention to something else. He had been cultivating a Latin dance sound ever since discovering a group called Raul Trana and the Nicaraguans in a Hollywood nightclub the previous year. He had even gone so far as to record them for a single release. Now Sam had brought in a song with a Latin feel that Bumps was convinced could be Sam’s next big hit, and when they went into the studio again toward the end of June, several weeks after Sam’s triumphant homecoming, that was the number that Bumps was determined to concentrate on.

Sam had started writing more and more. He carried a blue spiral notebook with him everywhere he went, filling it up with his lyrics, sometimes even jotting down words while he was talking to you. One time he showed Herb Alpert a song he was working on, “and he asked me what I thought of the lyric, and it really seemed trite to me. [So] I asked him what does the song go like, and he pulled out his guitar and started playing. And all of a sudden this thing that looked so corny on paper just turned into this magical event. ’Cause he had a way of phrasing, a way of presenting his feelings that was uniquely his. I mean, he was talking right to you, he wasn’t trying to flower things up with words that didn’t connect. He had a very clear way of expressing himself.”

“If you listen to his lyrics,” echoed Herb’s songwriting partner Lou Adler, “they’re very conversational. And it’s something that he always expressed. He said, ‘If you’re writing a song that you really want to get to people, you’ve got to put it into a language that they understand.’” Although he was an avid reader of poetry, his rhymes were more a matter of feel than formality. “It didn’t matter if it was a real rhyme or not,” said Adler, “[as long as] it felt right. I’ve seen him pick up a guitar and, you know, almost talk to you in the way that he was writing. And maybe it’s a song or a lyric that he’ll never use. But it sounded good when he was doing it.”

He had his own decided ideas of production as well. With René Hall, who was writing most of Bumps’ arrangements by now, whether credited or not, Sam was always insistent on getting it exactly the way he imagined it in his mind’s eye. He was “stubborn,” said René, “[but] he knew what he wanted to do. He would come in [to my office] with his guitar—or Clif White would play the guitar, because Clif knew more chords—and he would [show] me what line he wanted, he’d hum what he wanted the bass to play, hum what he wanted the strings to play, he would tell you exactly what he wanted every instrument to play.” To Herb, a trumpet player with a somewhat formal approach to music, it was Sam’s uncanny ability to communicate—as much by gesture as by language—that allowed him “to set up an environment where the musicians felt comfortable enough to express themselves through Sam, and that was the key. He told me something once that’s riveted to me, it’s like a permanent memory. He said, ‘People are just listening to a cold piece of wax, and it either makes it or it don’t.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘You know, you listen to it, you close your eyes, if you like it, great. If you don’t, nobody cares if you’re black or white, what kind of echo chamber you’re using. If it touches you, that’s the measure.’”

One time Sam and Herb were listening to a young West Indian singer who was auditioning at the Keen studio. “He even brought his own box to put his foot on for the audition. And I was saying to myself, ‘Oh, wow, man, this guy has the whole tool kit. I mean, he’s nice to look at, he plays nice guitar, his songs are good, and he’ll look great on television!’ And Sam looked at me and said, ‘What do you think?’ So I told him, and he said, ‘Well, turn your chair around for a little while and listen to him.’ And I did, and, of course, nothing happened. And I said, ‘Oh, well, it’s not as good when I turn my back.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I know.’ But, I mean, that was Sam. He wouldn’t be intimidated by how you looked, it didn’t matter if you were handsome or funny-looking, he was listening for the feel.”

As to how Sam picked up the Latin sound (which had been pervasive since the mambo, rhumba, cha cha, and calypso crazes that had periodically swept through the music business over the past five years), it wasn’t any more a matter of conscious study, Herb felt, than the way Sam sang. “I don’t think he was listening to Tito Puente. Sam had his antennae up at all times, and I would guess that Sam just kind of took the concept [that Bumps had introduced to the Keen studio] and put his own stamp on it.”

The song that he and Bumps were planning to focus on, “Win Your Love for Me,” was a real departure for Sam. He recorded it at the Capitol studios on the same day that he finally laid down a satisfactory vocal for “Almost in Your Arms,” the theme from

Houseboat

that he had originally cut while he was in New York in March. The movie theme had been written by Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, the veteran Hollywood team who had come up with everything from Nat “King” Cole’s classic “Mona Lisa” to Debbie Reynolds’ “Tammy,” and there was no question that it would be the A-side of the single, both because of its cinematic pedigree and because of Bumps’ strong belief in upward musical mobility. But, however smoothly Sam delivered it, it remained a conventional romantic ballad, whereas his own composition had the airiness, the space, above all that inimitable sense of “motion” that so strongly marked Sam’s feel for a song.

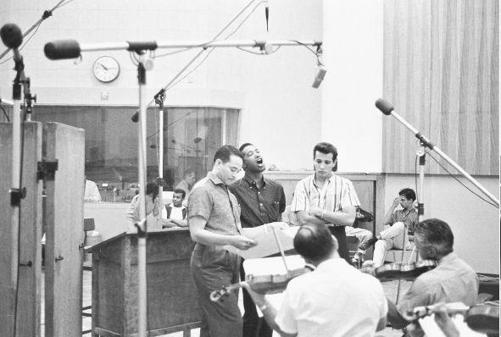

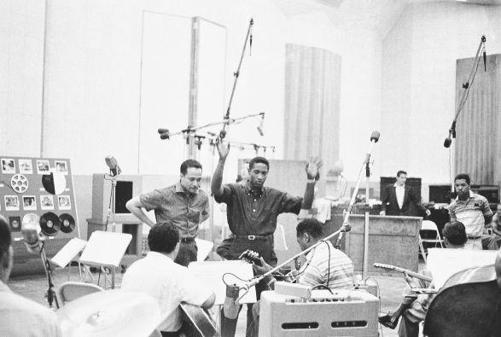

In the studio, 1958. Bumps Blackwell, Sam, and Herb Alpert.

Bumps and Sam.