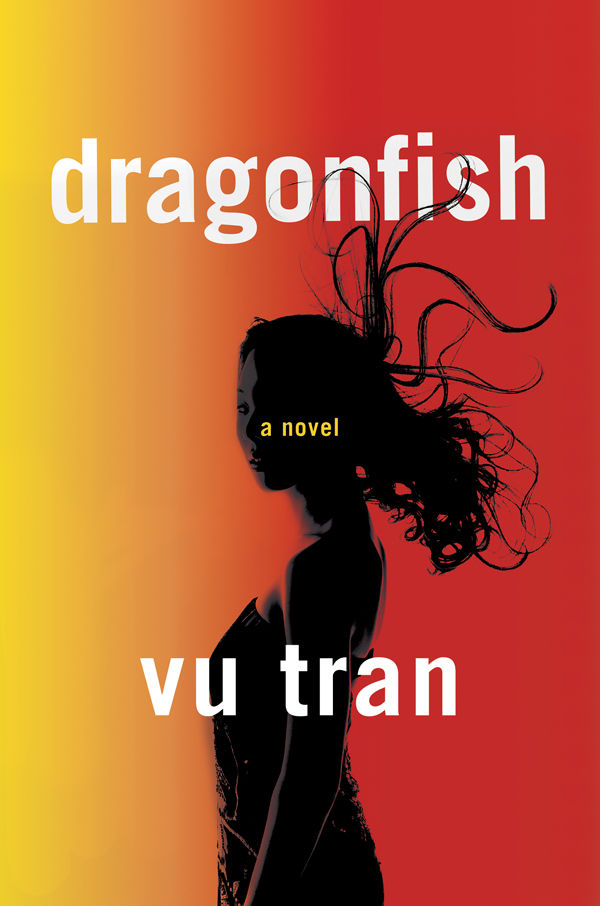

Dragonfish: A Novel

Read Dragonfish: A Novel Online

Authors: Vu Tran

dragonfish

a novel

vu tran

for my parents

dragonfish

Our first night at sea, you cried for your father. You buried your face in my lap and clenched a fist to your ear as if to shut out my voice. I reminded you that we had to leave home and he could not make the trip with us. He would catch up with us soon. But you kept shaking your head. I couldn’t tell if I was failing to comfort you or if you were already, at four years old, refusing to believe in lies. You turned away from me, so alone in your distress that I no longer wanted to console you. I had never been able to anyway. Only he could soothe you. But why was I, even now, not enough? Did you imagine that I too would die without him?

Eventually you drifted off to sleep along with everyone around us. People were lying side by side, draped across each other’s legs, sitting and leaning against what they could. In the next nine days, there would be thirst and hunger, sickness, death. But that first night we had at last made it out to sea, all ninety of us, and as our boat bobbed along the waves, everyone slept soundly.

I sat awake just beneath the gunwale with the sea spraying the crown of my head, and I listened to the boat’s engine sputtering us toward Malaysia and farther and farther away from home. It was the sound of us leaving everything behind.

The truth was that I too thought only of your father. On the morning we left, I held you in the darkness before dawn and lingered with him as others called for us in the doorway. He kissed your forehead as you slept on my shoulder. Then he looked at me, placed his hand briefly on my arm before passing it over his shaven head. I could see the sickness in his face. The uncertainty too, clouding his always calm demeanor. He had already said good-bye in his thoughts and did not know now how to say it again in person. I did not want to go, but he had forced me. For her, he said, and looked at you one last time. Then he pushed me out the door.

If you ever read this, you should know that everything I write is necessary to explain what I later did. You are a woman now, and you will understand that I write this not as your mother but as a woman too.

On that first night, as I watched your chest rise and fall with the sea, I wished you away. I prayed to God that I might fall asleep and that when I awoke you would be gone.

part

one

1

I

T WAS THREE IN THE MORNING

and dark in my apartment. I stood half naked behind the front door, peering through the peephole at my vacant porch. My voice had come out small and childish and like someone else’s voice calling from the bottom of a well.

“Who’s there?” I said again, louder, more forceful this time. The porch light flickered but I could see only the lonely rail of my balcony, the vague silhouette of trees beyond it.

I grabbed my officer jacket off the kitchen counter and slipped it on. I steadied the gun behind me, then slowly opened the door and let in the cool December air. The hair on my chest and legs bristled. I stepped onto the porch. No one on the stairwell. No one by the mailboxes. A sweeping breeze from the bay made my legs buckle. I peered over my second-floor balcony. In the darkened courtyard, strung over the elm trees, a constellation of white Christmas lights swayed.

I returned inside and locked the door. I crawled back into bed, back under the warm covers as though wrapping myself in the darkness of the room.

The two knocks that had awakened me resounded in my head, this time thunderous and impatient and so full of the echo of night that I asked myself again if I had heard anything at all. Could a knocking in your dreams wake you?

Some minutes passed before I placed my gun back on the nightstand.

“N

O ONE

out there to hurt you but yourself,” my father, a devout atheist, used to tell me. I never took this literally so much as personally, because my father knew better than anyone how selfish and shortsighted I can be. But whether he was warning me about myself or just naively reassuring me about the world, I have chosen, in my twenty years as police, to believe in his words as one might in aliens or the hereafter. They’ve become, it turns out, a mantra for self-preservation. Cops get as scared as anyone, but you develop a certain fearlessness on the job that you wear like an extra uniform, and people will know it’s there like your shadow slipping its hand over their shoulder, and intimidated or not they’ll think twice about hurting you. It’s an armor of faith, a wish etched in stone. Go ask a soldier who’s been to war. Or a priest. Or a magician. Without it, without that role to play, everything is a cold dark room in the night.

M

Y PHONE RANG

at six the next morning, an hour after my alarm woke me. I was already in uniform, coffee cup in hand and minutes away from walking out the door. As soon as I answered, the phone went dead—just like the previous morning.

I went to the window and peeked through the mini blinds at the parking lot below. No one was up and about at that early

hour, and the morning was still a stubborn shade of night. I made a fist of my left hand, unfurled it. My fingers had healed along with the pink scar on my wrist, but a warmth of unforgotten pain bloomed again. I stood there gazing at the lot until I finished my coffee.

Two days before this, I had come home from my patrol and found the welcome mat slightly crooked. Easily explainable, I figured, since any number of people—mailman, deliveryman, one of those door-to-door religious types—could have come knocking during the day. But once inside I noticed an unfamiliar smell, like burnt sugar, like someone had been cooking in the apartment, which I never do. In my bedroom, the pillows on the bed were in the right place but looked oddly askew, and one of my desk drawers had been left an inch open. It’s always been the little things I notice. Show me a man with three eyes, and I’ll point out his dirty fingernails.

The same smell greeted me the next evening as soon as I opened the front door. It followed me through the living room, the kitchen, the bedroom, the living room, the kitchen, fading at times so that I found myself sniffing the air to reclaim it, as I did as a boy when I roamed the house for hours in search of a lost toy or some trivial thought that had slipped my mind. Then the smell vanished altogether. Half an hour passed before I finally went to the bathroom and saw that the faucet was running a thin stream of water. I shut it off, more than certain that I had checked it before leaving that morning, something I always did at least twice.

I closed all the window blinds and spent the next two hours combing through all my drawers and shelves, opening cabinets and closets, searching the entire apartment for something missing or out of place, altered in some way. I knew it was ridiculous. Why would they go sifting through my medicine cabinet or my

socks? Why move my books around? I suppose checking everything made everything mine again, if only temporarily.

That night I went to bed with my gun on the nightstand, something I hadn’t done in nearly five months, since those first few weeks back from the desert.

I’d been trained on the force to trust my gut, or at least respect it enough to never dismiss it; but it crossed my mind that I was imagining all this, that in the previous five months I’d been glancing over my shoulder at shadows and flickering lights. You fixate on things long enough and you might as well be paranoid, like staring at yourself in the mirror until you start peering at what’s reflected behind you.

When the phantom door knocks awoke me that same night, I lay in bed afterward and waited. I was that boy again, hearing the front door slam shut in the middle of the night and measuring the loudness and swiftness and emotion of that sound and whether it was my mother or father who’d left this time, and then waiting for the sound again until sleep washed away the world.

The lesson of my childhood was that if you anticipate misfortune, you make it hurt less. It’s a fool’s truth, but what truth isn’t?

When I got home the following evening, I stayed in my car and stared for some time at the dark windows of my apartment. I was still in uniform but driving my old blue Chrysler. A drowsy fog crawled in from the Oakland bay, a cataract on the sunset, the day, which now felt worn. “Empty Garden” played on the radio, a slow sad song I hadn’t heard since my twenties. I remembered the old music video, Elton John playing a piano in a vacant concrete courtyard amid autumn leaves and twilight shadows. I sat back and scanned the complex of buildings surrounding me and thought of Suzy and the flowers that decorated every corner of

our old house, and at the pit of me was not sadness or anger but the hollowness of forgetting how to need someone.

Three kids on bicycles glided past my car through fresh puddles left by the sprinklers. Some twenty yards away, an elderly man strolled the courtyard with his Chihuahua like a scared baby in his arms. In the building that faced me, three college guys were leaning over their balcony, smoking and leering at a pretty redhead who passed below them with a baby stroller. Then I saw a skinny Asian kid—a teenager—walk in front of my car, turn, and approach the window. He smiled and gestured for me to roll it down. His hands looked empty. He was wearing a Dodgers cap and an oversize blue Dodgers jacket zipped all the way to his throat. His smile was like a pose for a camera, and when he bent down to face me, he was all teeth.