Dragon of the Red Dawn: A Merlin Mission (6 page)

Read Dragon of the Red Dawn: A Merlin Mission Online

Authors: Mary Pope Osborne

Tags: #Ages 6 and up

BOOK: Dragon of the Red Dawn: A Merlin Mission

11.9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“Welcome to my castle,” said Basho.

“

T

his

is your castle?” said Jack.

Basho smiled. “In my heart, my humble cottage is grander than all the castles of the samurai,” he explained. “And my banana tree is more beautiful to me than all the beauty of the Imperial Garden.”

Jack and Annie stared at the large plant with the long, droopy leaves.

“I like this tree so much I have taken my name from it,” said Basho.

“Basho

means ‘banana tree.’”

“Cool,” said Annie. She looked around. “It’s nice here.”

Not really

, thought Jack. The cottage was shabby and the droopy banana tree looked scrawny and sad to him.

“Please come inside,” said Basho. He slipped off his sandals and left them outside. He picked

up a bundle of wood, then ducked through the low door that led into his hut.

Jack and Annie took off their shoes, too, and followed Basho into a small, shadowy room.

Basho opened his shutters to let in the evening air. “Please sit,” he said.

“Thank you,” said Jack and Annie. Jack looked around the room for chairs, but there

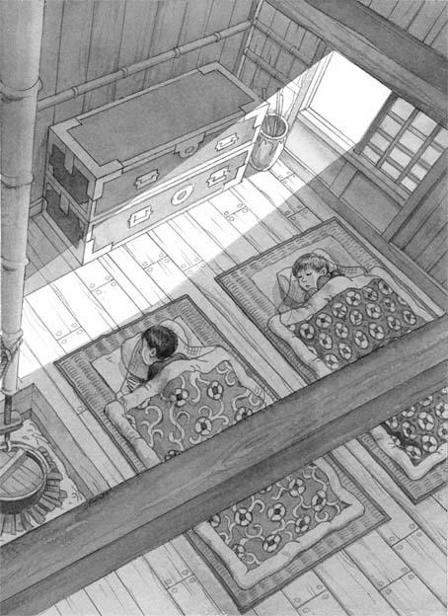

weren’t any. The only furniture was a low wooden table and a bamboo chest. Three straw mats covered the earthen floor. Jack and Annie sat down on one of the mats.

Basho lit a small oil lamp. Then he made a fire in his fireplace. “I will prepare tea for us,” he said. “Rest while I draw water from the river.” He picked up one of the two wooden buckets near the door and headed outside.

When Basho was gone, Jack and Annie looked at each other. “I guess this is a three-mat house,” said Annie.

Jack nodded. “You’d think a famous teacher of the samurai would have a hundred-mat house … or at least a fifty-mat house,” he said.

“I like this house, though,” said Annie. “It’s cozy.”

“I wonder who Basho is exactly,” said Jack.

“If he’s famous, maybe he’s in our book,” said Annie. “Look him up.”

“Good idea,” said Jack. He pulled the research

book out of his bag. By the light of the crackling fire, he looked up

Basho

in the index. “He

is

here!” Jack turned to the right page and read aloud.

Basho is one of Japan’s greatest poets.

He wrote short, beautiful poems that

speak to people as clearly today as they

did during the Edo period of Japan.

“Basho’s a great

poet

!” said Annie. “That explains everything!”

“Sort of …,” said Jack. “It explains why we had to recite poems to the samurai. But it doesn’t explain why Basho lives in such a dinky house.”

Basho opened the door and came in with his bucket. Jack closed the book and slipped it back into his bag.

Basho poured river water into an iron pot over the fire. He pulled three tiny bowls and a small cloth bag from the bamboo chest. He took loose green tea from the bag and dropped it into the bowls. Then he waited patiently for the water to boil.

Jack and Annie waited patiently, too. Listening to the soft rushing sounds of the river outside, Jack started to feel peaceful for the first time all day.

When the water was hot, Basho poured some into each of the tea bowls. Then he handed the warm bowls to Annie and Jack.

“Thank you,” said Annie.

“Thank you,” said Jack.

“You are welcome,” said Basho.

Jack carefully took a sip from the steaming bowl. The green tea tasted bitter, but he didn’t mind it.

“Hmm, interesting taste,” said Annie. “Basho, Jack was wondering, if you’re a famous poet, why do you live in such a dinky house?”

“Annie!” said Jack, embarrassed. “She’s kidding. I wasn’t really wondering that.”

Basho laughed. “Long ago, I trained to be a samurai,” he said. “But I was not happy. All I wanted to do was write poetry. A poet does not

need to live in a castle. A poet needs to live with the wind and the clouds, the flowers and the birds. Here, I have a small garden and my banana tree. I have the sound of the river all day long. Here, I have everything I need to write my poems.”

“What do you write about?” asked Annie.

“Small things,” said Basho. “A crow picking snails out of the mud, a woodpecker hammering a tree, pine needles scattered by the wind. A poet finds beauty in all the small things of nature.”

“And you teach poetry to the samurai?” asked Jack.

“Yes, the samurai greatly honor the art of poetry,” said Basho. “Poetry helps focus the mind. The samurai believe a truly brave warrior should be able to compose a poem even in the midst of an earthquake, or while facing an enemy on the battlefield.”

“Can you say one of your poems for us?” asked Annie.

“Let me think,” said Basho. “Well … I was working on a new poem yesterday.” He reached for a wooden box under the table. He took a small piece of delicate paper from the box and read aloud:

An old pond:

a frog jumps in—

the sound of water.

Basho looked up at Jack and Annie.

“Hmm,” said Jack. “Nice beginning.”

“It is not just the beginning,” said Basho. “It is the whole poem. A small moment in time.”

“I think it’s great,” said Annie. “I love frogs. Your poem makes me love them even more.”

“Would you read it again, please?” Jack said. He felt like he must have missed something.

Basho read again:

An old pond:

a frog jumps in—

the sound of water.

Jack nodded thoughtfully. “Good,” he said. “It’s really good.” And he meant it. The poem made him feel as if he himself had been right there, by that pond, hearing the frog splash into the water, breaking the silence.

“If you like it, you may have it,” said Basho. He handed the paper to Jack.

“Thanks!” said Jack. As he put the poem in his bag, a bell rang softly in the distance.

“Ah, the temple bells,” said Basho. He stood up. “It is time to rest. I will take a mat and sleep outside. I enjoy sleeping under the stars. And now, because of the poem you recited today, Annie, I shall think of them as diamonds in the sky.”

Annie smiled.

“You can stay inside and cover yourselves with these mosquito nets,” said Basho. He pulled some nets from the bamboo chest and handed them to Jack and Annie. “But do not worry, in my small house there are only small mosquitoes— not giant ones like those in the Imperial Palace.”

Jack and Annie laughed at Basho’s joke. He gave a net to each of them. Then he picked up one of the mats from the floor and pulled it outside, closing the door behind him.

The fire in the fireplace had died down. The light from the oil lamp had nearly gone out, too. Jack and Annie lay on the straw mats and covered themselves with the mosquito nets. A cricket chirped on the hearth. Jack noticed a patch of light on the floor. He realized it was moonlight coming through the open window.

Jack reached out from under the net and put his hand on the square of pale moonlight. He could hear the rustling of the banana plant in the breeze. Half asleep, he imagined himself swaying with its long, broad leaves.

“This dinky hut is much nicer than a castle,” Annie murmured. “I feel like we’re tiny crickets going to sleep.”

“Yeah … I feel like I’m holding moonlight in my hand,” said Jack, “and like I’m a banana leaf… dancing in the wind.”

“Sounds like a poem,” said Annie.

“Yeah … maybe I should write it down …,” said Jack. But instead, he fell fast asleep.

C

lang, clang, clang!

Jack opened his eyes. The sound of bells filled the night—not the gentle ringing of the temple bells but a harsh clanging.

Jack smelled smoke. He and Annie threw off their mosquito nets and stumbled to the door.

Basho was standing in his yard, looking at the dawn sky. It was black with smoke. The bells kept clanging.

“Is there a fire?” asked Jack.

“Yes,” said Basho. “It must be very big, for

the bells do not stop ringing from the watch-tower. This is what we have feared most. I must go and help the firefighters.”

“We’ll help, too,” said Jack.

“No, stay here,” said Basho. He pulled on his socks and sandals, then grabbed a wooden bucket by the door. “If the fire gets close, wade into the river, where you will be safe.”

“But we want to help!” said Annie.

“Yes, wait for us!” said Jack. He and Annie pulled on their socks and sandals.

“Come, then,” said Basho. “But if the fire begins to spread, you must promise to return here to the river.”

“We promise!” said Annie.

“Then bring the other bucket and follow me,” said Basho.

Other books

You're Making Me Hate You by Corey Taylor

Double Threat My Bleep by Julie Prestsater

Risking Ruin by Mae Wood

At Grave's End by Jeaniene Frost

The Genocides by Thomas M. Disch

Hindsight by Peter Dickinson

Poisoned Petals by Lavene, Joyce, Jim

Not Looking for Love: Episode 3 by Bourne, Lena

The Glass Wall by Clare Curzon

No Surrender by Hiroo Onoda