Dragon of the Mangrooves

Read Dragon of the Mangrooves Online

Authors: Yasuyuki Kasai

Under the lotus plants he lies down,

In the covert of the reeds and the marsh.

The lotus plants cover him with shade;

The willows of the brook surround him.

Job 40:21–22, Old Testament,

The New American Standard Bible

From the Author

On February 19, 1945, when World War II was about to end, saltwater crocodiles killed nearly a thousand Japanese infantrymen trying to break through the siege of the Allies in a mangrove around Ramree Island, Burma (Myanmar). And by the next morning, no more than twenty men had survived.

This story is known to some extent in former Allied countries, but it’s hardly circulated among the Japanese because we have no record verifying this in Japan. It was proven that no less than four hundred fifty soldiers made a safe return from the island to the continent, according to official war reports and many personal memo-randums. This means almost half the garrison was alive after the battle, which simply makes the casualties by crocodiles doubtful. But I do not believe the whole story is a downright falsity. During the World War II, Japanese occupation area was called the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere, and it was largely overlapped with the habitat of saltwater crocodiles. There were many reports of crocodile attacks, not only in the Burma Campaign but also in other southern fronts.

We tend to forget this kind of tale, compared with other atrocities of war.

Still, I think this story tells of war and symbolizes it effectively. War is becoming more mechanized and computerized, but its core is unchanged. That’s why I wrote this book.

In the nineteenth century, my great-great-grandfather was ordered by his feudal lord to go a long way to Edo (now Tokyo) to defend the coast against the oncoming American fleet, with only his ancient sword and armor to rely upon.

When the Pacific War broke out in 1941, my father and one of my uncles were conscripted and became an Army artilleryman and a Navy airman, respectively.

Both fought against the United States forces. Fortunately, they killed no one and came back alive. My ancestral history shows that some part of my family was ded-icated to fighting against foreigners. Of course, I have never fought with foreigners, apart from some fencing bouts and PC games. I appreciate this peace, and hope that it lasts forever.

Those who have studied or who took part in the Burma Campaign will know that the real names of troops, battles, and places were used. I used real names to give the story a semblance of reality. However, all other things are fictional, and any resemblance to a real person is coincidental. As for the names of countries and races, I followed the descriptive usage of that time period for the same reason.

The opening of the turret hatch cut into the morning sky of Bengal. Palm leaves rustled in the wind. But it was already intolerably muggy—like a sauna—inside the model ninety-seven tankette.

Second Lieutenant Yoshihisa Sumi no longer heard the buzz of enemy planes, but he couldn’t still the rapid beating of his heart. He picked out a damp cigarette and lit it with trembling fingers. Cigarettes were precious and shouldn’t be wasted in such a squalid place. Still, he took a puff eagerly, as he had no other option to calm himself under the circumstances.

Three or four enemy fighters had come on them as soon as Sumi’s Tankette Second Platoon had arrived at Taungup that early morning, following a hard run all night through the steep mountains of Arakan. All tankettes had immediately moved into this nearby jungle. He had been too frightened to discern whether they were American or British, to say nothing of their type. No matter what, he thought he had been done for a while in the din of engines and weapons fire permeating the jungle.

A small Burmese National Army (BNA) soldier squatted by the turret. He

seemed to feel no fear. His eyes moved rapidly, searching for enemy fighters.

Sumi stuck out his head from the hatch timidly. It was so bright outside that it made him dizzy.

“Have they gone, Pondgi?”

“Master Sumi, it’s all right. I can’t see them anymore,” replied Pondgi.

Sumi felt like a rodent that had escaped the talons of a bird of prey. Trying to block out this miserable feeling, he blew smoke out of his nostrils and said,

“Well, it’s annoying enough. We have to drive away those Engli bastards as fast as we can.” He knew it was a thin lie. It was the Japanese being driven away from Burma.

Pondgi still sat on the front hood and kept watching the sky. Pondgi had been with the Tankette Fifth Company of the Fifty-Fourth Reconnaissance Regiment, to which Sumi belonged since their platoon had left Rangoon. His Japanese pro-ficiency was remarkably high now.

“Pondgi” wasn’t his real name. Japanese servicemen believed the word meant a Buddhist monk in Burmese. Soldiers called him Pondgi because the name suited this calm, young guy with a skin head. He also seemed to like it, because Buddhist monks were highly respected here in Burma.

AWOL soldiers in the Burmese National Army had increased since the beginning of that year, 1945, and the number of overall troops had dropped sharply, as if it were keeping pace with the defeats of the Japanese Imperial Army. Now Burmese patience with their Asian conqueror was running out. Still, Pondgi never left them. He worked energetically every day. Sumi couldn’t understand what made him do so.

At first, Sumi had to report his arrival at Taungup to his company commander, who had gotten there first. If machine troubles and the air raid had not slowed their progress, Sumi’s platoon would have been there by dawn. He ordered subordinates to maintain tankettes in the jungle and went to the headquarters of the 121st Infantry Regiment. It was actually a bamboo shack behind a half-wrecked

temple at the edge of the town. Located on a strategic point of the Arakan front, it was often used by other troops as a communication spot.

Sumi kept walking on the coast road, where the Indian Ocean wind drove away the morning haze. Then he spotted the grand roofs of the old temple through the woods. Two servicemen were standing at the gate. One was Captain Yoda, his company commander, and the other seemed to be one of the division staff officers, whom Sumi had seen once or twice. Yoda was a calm man by nature but that day looked fidgety. Nervousness pervaded the place. Yoda recognized Sumi, who was prepared to be reprimanded for the delay. Instead, Yoda relayed some unexpected news. “Sumi, I’ve gotten a new order by wireless from the division commander, and I think you are just the man for the duty. Bear in mind it’s a division order. You got that?”

The company commander started reading a makeshift directive in a loud voice. “Second Platoon Commander, Second Lieutenant Sumi should organize a rescue party consisting of one squad, collect as many civilian boats as possible, and advance to Ramree Island with this party to help the Second Battalion of the 121st Infantry Regiment, a garrison of this island, evacuate to the continent…”

Sumi almost fainted. He couldn’t listen to the rest. Even as a low-ranking officer from a reserve officer candidate school, he knew that the situation on the Ramree front was deteriorating. He had to sneak into a tremendously dangerous place and rescue a badly mauled garrison. Sumi realized he had just been assigned an incredibly perilous duty.

In July 1944, the Japanese had miserably failed in Operation Imphal, the reckless offensive into India. The Army had lost nearly 55,000 men in the battle and to starvation during the retreat. Confronted with the Allies striking at full throttle after the victory, the Japanese Burma Area Army had already been repeating the debacle.

The Arakan area, where the Japanese Twenty-Eighth Army had been positioned to guard a southwestern Burma full of strategic points, was no exception.

Starting with a recapture of the very northwestern air field Akyab on January 3, 1945, British-Indian forces were fiercely attacking this area. On January 12, an enemy commando brigade landed in the Myebon Peninsula, fifty kilometers east of Akyab, where the main force of the Fifty-Fourth Reconnaissance Regiment had been guarding the coastline. The regiment was in the thick of a fierce battle.

Sumi’s company was on its way to provide reinforcement. Up until then, the company hadn’t engaged in a battle yet, thanks to Yoda, who had been finding every excuse to save his and his men’s lives.

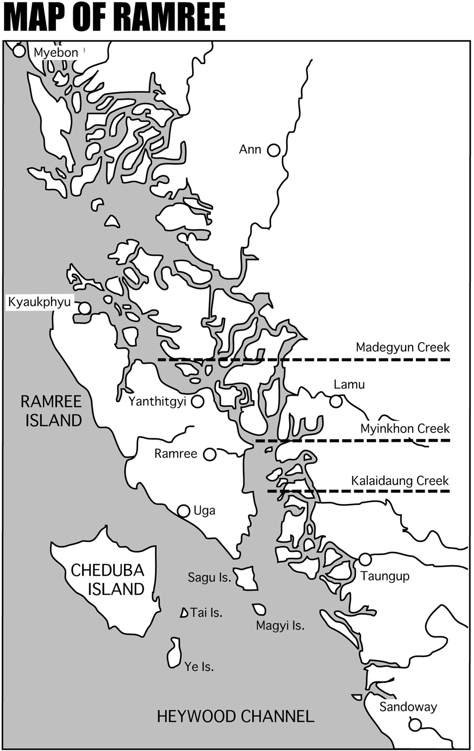

The 121st Infantry Regiment stayed here in Taungup—two hundred kilometers down the coastline from Myebon Peninsula—and guarded this area, including Ramree and the Cheduba Islands. Northwest of Taungup, Ramree Island is in the Bay of Bengal, divided by innumerable creeks through mangrove from the mainland. It is the biggest island in Burma. Cheduba Island, which flourished as a trading relay station of the East India Company in the old days, is located further southwest.

An enemy brunt finally reached Ramree Island on January 21. Reinforced

with a fleet including an aircraft carrier and battleships, the Twenty-Sixth Indian Division landed on Kyaukphyu, the northern port, that morning. The garrison challenging this was the Second Battalion of the 121st Infantry Regiment, supported only by six thirty-seven-millimeter antitank guns and three twenty-five PDR field guns taken from the British. Unable to resist the strength of one division, it had been cornered to the east coast until then.