Double Victory (18 page)

Authors: Cheryl Mullenbach

Lt. Florie E. Gant tends a patient at a prisoner of war hospital in England, October 1944.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WWII List #152

The Hospital in the Clouds

A picture of a black soldier lying in a hospital bed with a leg and both arms in slings caught the attention of Hazel Neal as she picked up a copy of the black newspaper the

Pittsburgh Courier.

It was the summer of 1945, and Hazel lived in Flagstaff, Arizona, while her husband, Grady, served with the US Army somewhere in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater of operations. Hazel couldn't believe her eyes when she read the print under the pictureâthe soldier was Grady!

From the newspaper account Hazel learned that the truck Grady had been driving had plummeted 350 feet over a cliff

and landed at the bottom of an embankment. He was carrying supplies over the newly constructed Ledo Road when his truck slipped off the muddy trail and over the cliff. His fellow soldiers pulled him from the truck, called an ambulance, and within a short time he was on his way to the 335th Station Hospital at Tagap, Burmaâa hospital staffed entirely with black medical personnel.

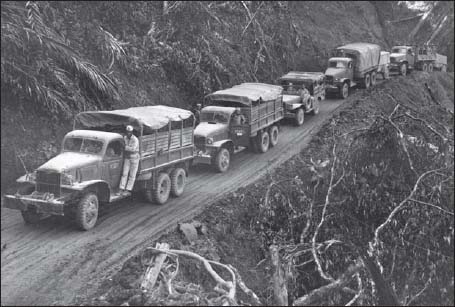

The construction of the Ledo Road had been “one of the greatest road building jobs in history.” Starting from Ledo, India, the Ledo Road joined with the existing Burma Roadâending up in China. The combined Ledo and Burma Roads were known as the Stilwell Road. The building of the Ledo Road and the rebuilding of the Burma Road were the result of an exhaustive undertaking by thousands of menâa combined force of Indians, Chinese, Burmese, Britons, Australians, and Americans. More than half the Americans were black soldiers.

US Army trucks wind along the side of a mountain over the Ledo Road between India and Burma.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WW II List #009

What made the task so incredible were the conditions under which the soldiers worked. The Ledo Road was being built through some of the most difficult terrain in the worldâswamps, jungles, and mountainsâtreacherous terrain for the men trying to construct a road for use by heavy military vehicles. As the soldiers inched their way through the jungle and over the mountain passes, they encountered torrential rains, extreme heat, and biting cold. If they managed to keep their vehicles on the winding trails they were lucky. But there were no guarantees that they wouldn't become deathly sick from malaria, cholera, or dysentery. And they had to contend with all the wildlifeâelephants, monkeys, tigers, panthers, lizards, and snakes.

When Grady Neal was delivered to the 335th Station Hospitalâalso called the hospital in the cloudsâthe all-black medical team was waiting for him. Included in the group were a handful of black army nurses. The hospital had been operating on the slope of the Patkai Mountain rangeâ4,500 feet up in the cloudsâfor only a few months. Before the 335th was established, men who were injured on the Ledo Road were transported by truck, jeep, raft, mule, or oxcart to hospitals that, depending on where the accident occurred, could be several hundred miles away.

In October 1944 a group of black army nurses had arrived in Tagap to help set up the hospital. Rose Robinson, Rosemae Glover, Polly Lathion, Rosemary Vinson, Fannie Hart, Anna Landrum, Caroline Schenck, Agnes B. Glass, Madine H. Davis, Margaret Kendrick, Elestia Cox, Lillie L. Lesesne, Olive Lucas, Eva Wheeler, Doshia Watkins, Rose Elliott, and Daryle Foister knew their work was important. The Ledo Road would be used by Allied armies to get supplies to Chinaâa strategically

that was struggling to defeat the Japanese armies in the CBI theater. Supplies were transported by planes to China, but it was a dangerous and costly undertaking by air. Planes heavily loaded with fuel and other supplies had to maneuver mountain peaks as high as 16,000 feet. The air trip consumed so much fuel that by the time a plane reached its destination, most of the precious cargo had been eaten up by the aircraft making the delivery. It was crucial that a land connection between India and China be made. The Stilwell Road was that connection.

Before patients could be treated at the 335th Station Hospital, the nurses helped the other members of the medical team convert the abandoned buildings that were to become their medical facilities into a modern laboratory, pharmacy, operating rooms, patient rooms, mess hall, and living quarters. They even had to install a water systemâusing pipes left behind by the Ledo Road engineersâto carry the water from high in the mountains for use in the hospital. A drainage system had to be built to handle the excess water that rushed down the mountainside during the rainy season. And because there would be

some

time for rest and relaxation, a baseball diamond, basketball court, and movie amphitheater were built into the mountain slope near the hospital.

Back home in Flagstaff, Arizona, Grady Neal's wife, Hazel, learned about the 335th Station Hospital from newspaper articles. Grady had tried to protect his wife from worryâhe had told her he was suffering from a bout with malaria. Although Grady's injuries from his tumble over the Ledo Road mountainside were very serious, the all-black medical team at the hospital was well prepared to treat his injuries.

Rose Robinson from Pennsylvania was the chief operating room nurse. Elestia Cox from California and Rosamae Glover from Ohio were nurse supervisors. Rosemary Vinson from

Michigan was the hospital dietitian. Rosemary Vinson, Fannie Hart, Anna Landrum, Caroline Schenck, and Daryl Foister had served in the 25th Station Hospital in Liberia before coming to work at the hospital in Burma. Daryl had worked in hospitals in Pennsylvania and New York before joining the Army Nurse Corps. She was positive about her overseas experiences. “I haven't minded my overseas duty,” she remarked. “I've learned a lot about the customs and habits of foreign peoples.”

Hazel Neal couldn't help but worry about her husband after seeing his picture in the newspaper and learning about the seriousness of his injuries. But she could be comforted knowing he was being cared for by a top-notch medical team high in the clouds over Burma.

They Just Accept Us

“They just accept us, like us, and no questions are asked,” black army nurse Ora Pierce said about the German soldiers she saw every day when she went to work.

Black army nurses had traveled to all corners of the world to care for American soldiers who had been wounded by the enemy. Some black nurses had cared for enemy prisoners in England. Ora Pierce stayed in the United States, and the enemy came to her.

In September 1945, Ora and 29 black army nurses were stationed at a hospital in Florence, Arizona. Over 30,000 German prisoners passed through the distribution center on their way to work in labor camps in other states across the country.

Some of the prisoners had been away from home for as long as seven years, Ora said. Some of them talked about how they had been captured by the Americans. But all of them wanted to tell the nurses about their homes. Ora thought most of the prisoners were like American soldiersâthey were homesick and liked to talk about their wives and sweethearts. “I have yet to meet one [soldier] who didn't want to talk, right off the bat, about homeâwhether it be in Kansas, New York, or Berlin.”

A group of army nurses. Ora Pierce is third from right.

Courtesy of the Fort Huachuca Museum

Besides caring for sick and injured prisoners, Ora supervised the work of 36 prisoners who worked in the hospital with her nurses. One of the Germans was Ora's assistant in the physical therapy department. He had been a physical therapist in Germany before the war.

“On the whole,” Ora remarked, “they are extremely co-operative and polite. As gestures of friendliness, they have made name plaques and jewel boxes carved from wood for every one of the Negro nurses.”

While the enemy prisoners were accepting and friendly to the black army nurses, that wasn't the case with some Americans.

When the nurses arrived in Florence, five white civilian nurses worked at the hospital. When they learned that the black army nurses were coming, the white nurses were so displeased that they quit their jobs rather than work with the black nurses.

And although Ora and her nurses were welcome in the white officers' mess hall, this came about only after some of the nurses complained to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People earlier in the yearâwhen they had been segregated from their white counterparts during meal times.

The situation at Florence had definitely changed between January and September 1945. “Maybe it's being isolated on a desert,” Ora commented, “but there is a real feeling of co-operation and friendliness at Florence.”

Ora Pierce said the German POWs “just accepted” the black nurses at the Florence prison camp. Injured Germans were cared for by the nurses in the camp hospital. Others worked alongside Ora and the other nurses. If the German prisoners could accept the nurses, maybe white Americans would accept black Americans if they had opportunities to work with them. But in the 1940s, discrimination and segregation prevented those opportunities.

The America They Hoped to Live In

Many black women were eager to serve their country in the military during the war. But for black women it wasn't as simple as signing up. The army allowed black women to join early in the warâalthough their numbers were restrictedâbut the other branches of the military were much slower in allowing black women into their ranks. Despite a critical need for nurses during the war, the army and navy nurse corps were reluctant to open their doors to black women. And those nurses who did

get into the military and the nurse corps were forced to live in segregated environments. And sometimes they were forced to endure blatant racism.

When the Dallas coffee shop worker had refused to allow Louise Miller to sit in the front of the restaurant in 1945 as she traveled home to visit her sick father, he couldn't see past the color of Louise's skin. He didn't see a woman who had served her country in a war zone. But Louise knew this individual's actions were indicative of a much deeper problem in America. She spoke of “the America we live in.”

Louise was talking about the racism that was tolerated and accepted in Americaâincluding in the military. The America Louise lived in was one that required black women serving their country to live in separate barracks from white women. It was an America that “purified” the swimming pool at a military post after black officer candidates swam in it. It was an America where a recruiting office closed down rather than give applications to black women. It was an America where the color of a person's skin overshadowed the uniform.

Despite these humiliating experiences, Louise Miller, Charity Adams, Sammie Rice, Ora Pierce, Birdie Brown, and thousands of other black women wore the uniform of the American military and hoped that someday in the future the America they lived in would be able to see beyond the color of their skin.

VOLUNTEERS

“Back the Attack”

“When I turned my back, the policeman named Dean kicked me. When I turned, he slapped my face and struck me on the shoulder with his fist.”