Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (10 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

She knows,

I think to myself.

She knows I killed Olivia and she hates me now.

And she’ll hate me forever.

The next morning I go into Olivia’s room and look in the cot. The bed is still rumpled from her body from the morning before. Her toys are spread about on top of her sheets. Her pajamas are folded up on her pillow. Mum has buried her face in Olivia’s bedclothes and when I come in, she looks up at me. She says, in a smothered voice, “It still smells of baby.”

For a long time after that, Mum was very quiet most of the time. The Burma Valley farmers pool their money and write us a check so that we can go on holiday, maybe to South Africa to the beach, they say. But Dad won’t cash the check. He says, “We’re all hard up. They’re hard up, too.” He frames the check and hangs it in the sitting room. He says, “Let’s drive around Rhodesia for a holiday. We’ll take tins of food and sleeping bags. It won’t cost much.”

So we bury Olivia in a little baby-sized coffin in the cemetery where the old white settlers are lying in their big, proud graves with moss-covered white gravestones and permanent pots of flowering plants and careful, exclusive fences which are there for show and do nothing to stop the monkeys running onto the graves. And after Olivia is buried, we drive to the nearest house; all the families in the Burma Valley in their most careful, sad clothes driving in a long segmented snake of sad-slow cars to an Afrikaner’s house, and we eat the sweet greasy

koeksisters

and pound cake and scones that the Afrikaner women have been baking all morning and we drink sweet milky tea until someone finds a bottle of brandy and some beers and starts to hand those around. Which gives us the courage to have a small church service in the only way we know how as a community: drunk and maudlin. Alf Sutcliffe pulls out his guitar. He doesn’t know church songs, so we sing “You picked a fine time to leave me, Lucille” and “Love me tender” until even the grown men, even the tough old Boer farmers, are wiping away tears with the backs of their hands.

A few days after the funeral, we pack ourselves into the green Peugeot station wagon and drive up and out of the valley. But we couldn’t drive away from the memories of the baby who lay under the soft, silent pile of red-fertile soil cut into a barely contained cemetery against the edge of the valley floor where mostly old people lie rotting gently in the rains and drying to dust in the dry season.

No one ever came right out and said in the broad light of day that I was responsible for Olivia’s death and that Olivia’s death made Mum go from being a fun drunk to a crazy, sad drunk and so I am also responsible for Mum’s madness. No one ever came right out and said it in words and with pointing fingers. They didn’t have to.

Mum

AFTERWARD

My life is sliced in half.

The first half is the happy years, before Olivia dies.

Like this: Vanessa and the older neighbor children are sitting with their feet dangling over the windscreen; their legs are speckled with nuggets of red mud. We are sitting behind the big brothers and sisters—we minor offspring—and we are using them as a shield against the slinging flicks of mud and the fat, humid wind, which grows colder as the evening comes.

“Sing,” Dad shouts at us, threatening to catapult us from the roof by steering the car into a sliding halt, “sing!”

We are hilarious with half-fright, half-delight, the way Dad drives. Olivia is on Mum’s lap in the front seat, screaming with excitement. Her sweet, baby happiness comes up to us on the roof in snatches.

“He’s

penga

!” says one of the big brothers.

And then someone starts,

“Because we’ re”

—pause—

“all Rhodesians and we’ll fight through thickanthin!”

and we all join in.

And Dad shouts, “That’s better!” and presses the car forward, freckling the big brothers and sisters with newfound mud.

We throw back our heads.

“We’ll keep this land”

—breathe—

“a free land, stop the enemy comin’ in.”

We’re shout-singing. We’ll be Rhodesian forever and ever on top of the roof driving through mud up the side of the mountain, through thick secret forests which may or may not be seething with terrorists, we’ll keep singing to keep the car going.

“We’ll keep them north of the Zambezi till that river’s runnin’ dry! And this great land will prosper, ‘cos Rhodesians never die!”

The spit flies from our mouths and dries in silver streaks along our cheeks. Our fingers have frozen around the roof rack, white as bones. We are ecstatic with fear-joy.

The second half of my childhood is now. After Olivia dies.

After Olivia dies, Mum and Dad’s joyful careless embrace of life is sucked away, like water swirling down a drain. The joy is gone. The love has trickled out.

Sometimes Mum and Dad are terrifying now. They don’t seem to see Vanessa and me in the back seat. Or they have forgotten that we are on the roof of the car, and they drive too fast under low thorn trees and the look on their faces is grim.

We are not supposed to drive after dark—there is a curfew—but the war and mosquitoes and land mines and ambushes don’t seem to matter to Mum and Dad after Olivia dies. Vanessa and I sit outside at the Club while Mum and Dad drink until they can hardly open the car door. We are on the tattered lawn, around the pond where Olivia drowned (fenced off now, and empty for good measure). Mosquitoes are in a cloud around our ankles, and Mum and Dad do not care about malaria. We are sunburnt and thirsty, bored. We lie back on the prickling grass and watch the sky turn from day to evening.

Dad

We drive home in the thick night through the black, secret, terrorist-hiding jungle on dirt roads and Dad has his window down and he is smoking. The gun is loaded across his lap.

Vanessa and I have not had supper.

So Mum and Dad buy us more Coke’ n’ chips for the drive and tell us to sit in the back seat with the dog, who has been forgotten about in the car all afternoon and who needs a pee.

We let Shea out for a pee.

Mum is fumbling-drunk and Dad, who is sharp-drunk, is getting angry.

“Come on,” he says to Shea, aiming a kick at her, “in the bloody car now.”

“Don’t kick her,” says Mum, indistinctly protective.

“I wasn’t kicking her.”

“You were, I saw you.”

“Get in the bloody car, all of you!” shouts Dad.

Vanessa and I quickly climb into the car and start to fight about where Shea should sit. “On my lap.”

“No, mine.”

“Mine. She’s my dog.”

“No, she’s not.”

“

Ja,

she is. Mum, is Shea my dog or Bobo’ s?”

“Shuddup or I’ll give both of you a bloody good hiding.”

Vanessa smirks at me and pulls Shea onto her lap. I stick my tongue out at Vanessa.

“Mum, Bobo pulled her tongue at me.”

“I did not.”

Mum turns around and slaps wildly at us. We shrink from her flailing hand. She’s too drunk and sad and half-mast to hit us.

“Now another sound from either of you and I’ll have you both for bloody mutton chops,” says Dad.

That’s that. Mutton chops is not what we want to be. We shut up.

Vanessa and I eat our chips slowly, one at a time, dissolving them on our tongues, and the vinegar burns so we swallow Coke to wash down the sting. We each feed Shea three or four chips. She missed her supper too.

Dad drives wildly, but it’s not children-on-the-roof-wild which is fun and scary all at the same time and we’re singing and the saliva is stringing from our mouths in thin silver ribbons. This is the way a man drives when he hopes he will slam into a tree and there will be silence afterward and he won’t have to think anymore. Now we are only scared.

Mum has gone to sleep. She is softly, deeply drunk. When Dad slows down to take a corner, she sags forward and hits her forehead damply on the dashboard and is startled, briefly, awake. The car is strong with the smell of cigarette smoke and stale beer. Burped-and-farted beer. Breathed-out beer. In the dark we watch the bright red cherry from Dad’s cigarette. It lights his face and the lines on his face are old and angry. Vanessa and I have finished our Coke’ n’ chips. Our tummies are full-of-nothing-aching-hungry. Shea is asleep on Vanessa’s lap.

If we crash and all of us die it will be my fault because Olivia died and that made Mum and Dad crazy.

That’s how it is after Olivia dies.

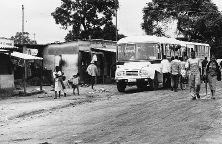

Bus stop

VACATION

The house is more than we can stand without Olivia. The emptiness of life without her is loud and bright and sore, like being in the full anger of the sun without a piece of shade to hide under.

Dad has said we’ll go on holiday.

“To where?”

“Anywhere. Anywhere that isn’t here.”

So we drive recklessly through war-ravaged Rhodesia.

A green Peugeot rattling along the desolate black strips of tar with toilet paper flying victoriously from the back windows (where Vanessa and I were seeing how long it could go before it tore off and lay behind us on the road like a fat, white run-over snake, twisting in agony). As the roads of Rhodesia uncurled in front of our new, hungry sorrow, we sang,

“One man went to mow, / Wenttomowameadow,”

and

“One hundred baboons playing on a minefield. And if one baboon should accidentally explode, there’ll be ninety-nine baboons playing on a minefield.”

And when we stop singing, Dad shouts, “Sing!”

So we sing,

“Because we’ re”

—pause—

“all Rhodesians and we’ll fight through thickanthin, / We’ll keep this land a free land, stop the enemy comin’ in. / We’ll keep them north of the Zambezi till that river’s runnin’ dry / And this great land will prosper ‘cos Rhodesians never die.”

And we sing,

“Ag pleez, Daddy won’t you take us to the drive-in? / All six, seven of us eight, nine, ten.”

Until Mum says, “Please, Tim, can’t we just have some quiet? Hey? Some peace and quiet.”

Mum is quietly, steadily drinking out of a flask that contains coffee and brandy. She is softly, sadly drunk.

Dad says, “Okay, kids, that’s

enoughofthat.

”

So we sit on each side of the back seat with the big hole in the middle where Olivia should be and watch Mum’s eyes go half-mast.

We are driving through a dreamscape. The war has cast a ghastly magic, like the spell on Sleeping Beauty’s castle. Everything is dormant or is holding its breath against triggering a land mine. Everything is waiting and watchful and suspicious. Bushes might suddenly explode with bristling AK-47s and we’ll be rattled with machine-gun fire and be lipless and earless on the road in front of the burned-out smoldering plastic and singed metal of our melting car.

The only living creatures to celebrate our war are the plants, which spill and knot and twist victoriously around buildings and closed-down schools in the Tribal Trust Lands, or wrap themselves around the feet of empty kraals. Rhodesia’s war has turned the place back on itself, giving the land back to the vegetation with which it had once been swallowed before people. And before the trappings of people: crops and cattle and goats and houses and business.

And then, through deep-quiet, long-stretching-road boredom and quite suddenly, and as surprising as the Prince battling madly through briars to reach a sleeping woman he has never met, two white figures appear on the road. They aren’t princes. Even from afar we can tell they aren’t princes. They look stained gray-brown in filthy travelers’ clothes with unruly hair sticking up with grease and dirt. They aren’t Rhodesians either, we can tell, because they are walking along the road and white Rhodesians don’t walk anywhere on a road because that’s what Africans do and it is therefore counted among the things white people do not do to distinguish themselves from black people (don’t pick your nose in public or listen to

muntu

music or cement-mix in your mouth or wear your shoes hanging off at the heel). One of the walking white men sticks out his thumb as we approach.

Mum slumps forward damply as Dad slows down. Dad gives her an anxious look. Mum feels his glance and smiles crookedly. She says, “Why are you slowing down?”

“Hitchhikers.”

“Oh.”

Dad says, “Well, I can’t bloody well leave them on the side of the road, can I?”

“I don’t see why not. It’s where we found them.” Mum, who picks up every stray animal she ever sees.

Dad says, “Stupid bloody buggers.”

At this point in our journey, when we see the hitchhikers, Vanessa has built a barrier of sleeping bags and suitcases between us so that she doesn’t have to look at me because, she has told me, I am so disgusting that I make her feel carsick. We have run out of the toilet paper we had brought for the trip. It now lies strewn in our wake or clings, fluttering, to thorn trees by the sides of the road. We have played I Spy until we accused each other of cheating.

“Mu-uuum, Bobo’s cheating.”

“I’m not, Vanessa is.”

“It’s Bobo.”

I start crying.

“See? She’s crying. That means she was cheating.”

Mum turns around in her seat and swipes ineffectually at us, slow-motion drunk. Until now she has been spending an agreeable hour looking at herself in the rearview mirror and trying out various expressions to see which most suits her lips. Now she says, “Anything more from either of you and you can both

getoutandwalk.

”

Like a hitchhiker.

And now this. The two

mazungu

figures looming out of the hot rush of road.

“We don’t have room for hijackers,” says Vanessa, pointing at the pile between us and the back of the car, which is already stuffed to overflowing with suitcases and sleeping bags.

“Hear that, Tim, ha ha. Vanessa calls them hijackers.”

Dad stops and shouts out the window. “Where are you going?”

“Wherever you’re going,” says the little blond one in an American accent.

“We don’t have a plan,” says Dad, getting out and trying to make room for the two men among our luggage, among the sleeping bags, between Vanessa and me.

“That’s fine with us,” says the little one.

“Not us,” mutters Vanessa.

The hitchhikers squeeze into their allotted spaces and Dad drives on through the empty land.

The little one says, “I’m Scott.”

“You’re a bloody idiot,” says Dad.

Scott laughs. Dad lights a cigarette.

The big, dark one says, “I’m Kiki.” He has a thick German accent.

Mum turns around and smiles expansively to make up for Dad’s unfriendliness. “I’m Nicola,” she says, and then the effort of staring back at our new passengers obviously does not mix with coffee and brandy because she pales, hiccups, and turns abruptly to the front.

“I’m Bobo,” I say. “I’m eight. Nearly nine.”

Dad says, “Did you know there’s a war on?”

“Oh,

ja.

Ve thought it vould be a good time to travel. Not too many other tourists.”

Dad raises his eyebrows at our hitchhikers in the rearview mirror. He has sky-blue eyes that can be very piercing. He blows smoke out of his nose and flicks ash out of the window and his jaw starts to clench and unclench so I know it will be a long time before he speaks again.

I say, “And that’s Vanessa, she’s eleven, nearly twelve.”

Our avocado-green Peugeot heads into the sunset, toward the Motopos Hills. We stop to pee behind some bushes and Mum gives us each a banana and a plastic mug of hot, stewed tea from the thermos flask. We’re all reluctant to get back into the car. Kiki sleeps, Scott reads. Dad smokes, Mum looks at herself in the side mirror. I am reduced to staring out of the windows. Reading my collection of books (I have brought a small library to accompany me on my journey) is making me carsick, and the pungent rotting-sausage smell emanating from Kiki’s socks doesn’t help. The effort of being confined in a small space is making Kiki sweat. With six of us in one station wagon, Kiki has to lie with his nose pressed against the roof, on top of the suitcases and sleeping bags in the rear of the car. His feet poke out on either side of Scott and me.

On the stretches of road that pass through European settlements, there are flowering shrubs and trees—clipped bougainvilleas or small frangipanis, jacarandas, and flame trees—planted at picturesque intervals. The verges of the road have been mown to reveal neat, upright barbed-wire fencing and fields of army-straight tobacco, maize, cotton, or placidly grazing cattle shiny and plump with sweet pasture. Occasionally, gleaming out of a soothing oasis of trees and a sweep of lawn, I can see the white-owned farmhouses, all of them behind razor-gleaming fences, bristling with their defense.

In contrast, the Tribal Trust Lands are blown clear of vegetation. Spiky euphorbia hedges which bleed poisonous, burning milk when their stems are broken poke greenly out of otherwise barren, worn soil. The schools wear the blank faces of war buildings, their windows blown blind by rocks or guns or mortars. Their plaster is an acne of bullet marks. The huts and small houses crouch open and vulnerable; their doors are flimsy pieces of plyboard or sacks hanging and lank. Children and chickens and dogs scratch in the red, raw soil and stare at us as we drive through their open, eroding lives. Thin cattle sway in long lines coming to and from distant water and even more distant grazing. There are stores and shebeens, which are hung about with young men. The stores wear faded paint advertisements for Madison cigarettes, Fanta Orange, Coca-Cola, Panadol, Enos Liver Salts (“First Aid for Tummies, Enos makes you feel brand new”).

I know enough about farming to know that the Africans are not practicing good soil conservation, farming practices, water management. I ask, “Why?” Why don’t they rotate? Why do they overgraze? Where are their windbreaks? Why aren’t there any ridges or contours to catch the rain?

Dad says, “Because they’re

muntus,

that’s why.”

“When I grow up, I’ll be in charge of

muntus

and show them how to farm properly,” I declare.

“You’re quite a little madam,” Scott tells me.

“I’m a jolly good farmer,” I tell him back. “Aren’t I, Dad, aren’t I a good farmer?”

“She’s an excellent farmer,” says Dad.

I smirk.

Vanessa sinks further into herself. She waits until I look over at her and wipes the smug look off my face with one, mouthed word: “Freak.”