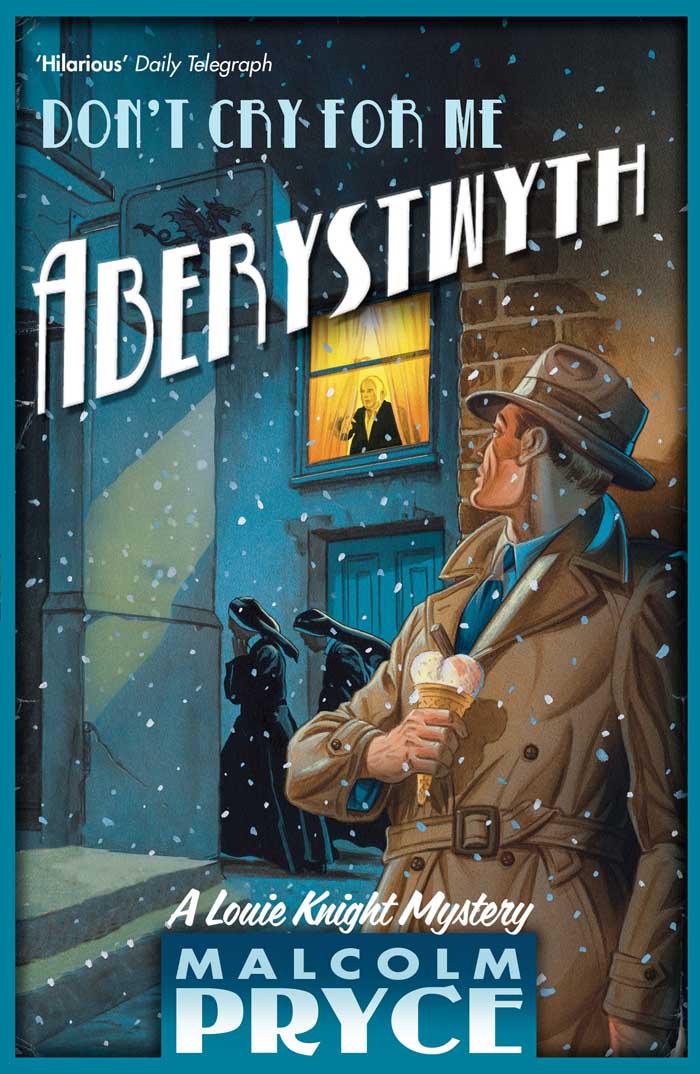

Don’t Cry For Me Aberystwyth

Read Don’t Cry For Me Aberystwyth Online

Authors: Malcolm Pryce

To Wilhelm Warth

Mrs Powell’s first cousin had left Patagonia and gone back home to Wales.

‘He

has

done well,’ she said. ‘He’s now the Archdruid.’

In Patagonia

, Bruce Chatwin

A

berystwyth at Christmas. The smell of pine drifts along the Prom mingling with the reek of bladderwrack, toffee apple, vanilla and wet donkey fur . . . From somewhere beyond the spires of the old college children sing ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’, and the siren from the distant prowl car wails in harmony. The ice man shivers behind his empty counter and in a filthy alley in Chinatown a man in a red-and-white coat with a long white beard lies dead in a pool of his own gore. In happier times the red robes of his office – like the red cross of Switzerland – conferred a species of neutrality in the never-ceasing disputes that wash over the Prom; but these are not happy times. The cruel melancholy of his death is heightened by an extra finesse: his manhood has been hacked off and placed in his mouth. And with the last of his strength the man has dipped a finger in his own blood and written a word on the pavement: ‘Hoffmann’. With the blood beginning to freeze and glitter like raspberry ripple, the school art teacher, Mrs Dinorwic-Jones, kneels beside the dead Santa and prepares to draw a chalk outline around the corpse. Just like so many times before; but this is not like the times before. Her hand shakes uncontrollably and tonight the white chalk line zig-zags in and out like the outline of an electrocuted polecat. Aberystwyth at Christmas. Compliments of the Season.

Editorial,

Cambrian News

, Christmas 1989

WHEN I ARRIVED next morning flakes of snow were swirling like moths in the penumbra of the street-lamp outside the office. There was a car parked on the kerb and two moths sat inside. The Moth Brothers. Two men in their late fifties who took care of debt collection for the druids. The difficult cases, the type that are often fulfilled by a transition to the state that proverbially pays all debts: the state of not being alive very much. They were identical twins; so alike, it was said, that the only way their mother could tell them apart was from the pattern their tiny moth teeth left on her nipple when she suckled them. In later years it was their victims who had to be identified by their teeth. They had heads that were bigger than they should be, and big eyes that were placed too far to the side of the head. Their skin had the pallor of candle wax and the texture of ear wax. No one knew whether they had always looked like moths or had grown to look like them the way some people grow to resemble their pets. Maybe they acquired the name because they usually came out at night; or maybe it was something do with the habit they had of leaving their clients’ clothes full of holes. When they saw me they stepped out of their car and followed me up the stairs into the office. I didn’t offer them a drink.

‘We’ve come to claim our reward,’ said Meic. I knew it was Meic because he had a big M on the front of the sweater he wore under his jacket. Othniel wore an O.

‘Reward for what?’

‘The Father Christmas murder. We know who did it. That means we get some books, right?’

‘On philosophy,’ added Othniel.

‘By some Danish bloke. Exis . . . exis . . .’

‘Stentialism, that’s our favourite.’ Othniel pulled out a copy of the

Cambrian News

folded to the classified ad. ‘See?’

I took the paper and made a great play of reading it, even though I knew what it said. They fidgeted while I read, so I took some more time.

‘We haven’t got all day,’ said Meic.

I put the paper down and regarded them. ‘It certainly seems to be in order, all here in black and white. Anyone who gives me useful information that helps track down the culprits gets a signed first edition of the works of Søren Kierkegaard. First editions are difficult to come by so I can understand your excitement.’

‘We’re all a-tizz,’ said Meic.

‘OK, then, who killed him?’

Meic pointed at Othniel and said, ‘He did!’

Othniel pointed at Meic and said, ‘He did!’

‘There’s only one set of books.’

‘We don’t mind sharing.’ They laughed.

‘And I bet you’ve both got alibis, too.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Let me guess. You were with him and he was with you the whole night.’

‘That’s right,’ they said in unison. ‘The whole night.’

‘So there’d be no point me trying to run you in.’

‘You don’t think so?’

‘Not with alibis provided by two upstanding members of the community.’

‘We hadn’t thought about that.’

‘Couple of nice guys like you, loved by everyone, what sort of jury would convict you?’

‘Oh dear, it looks like our attempt to turn ourselves in has been thwarted,’ said Othniel.’

‘No books for us,’ added Meic with mock gloom.

‘And given the way you both look so alike, you couldn’t absolutely swear in a court of law that it was Meic you saw on the night in question and not your own reflection in a puddle or something; and you, Meic, couldn’t absolutely swear it was Othniel you saw and not a reflection in a puddle or something, isn’t that right?’

‘That’s a good point,’ said Meic. ‘He and I look so much alike the only way I know who I am is to look at his jumper. But what if someone swapped them during the night? How would I know?’

‘In fact, we recently beat up a chap from the philosophy department who made precisely the same point. He said it had to do with discontinuity of the narrative self.’

‘Apparently there’s no way anyone can be sure that the memories they wake up with belong to the same person who went to bed.’

‘You could wake up as a different person and there’d be no way to tell.’

‘He still doesn’t know which one of us hit him.’

‘And to be honest, in light of the doubt spawned by his scepticism, neither do we.’

They laughed.

I laughed, too, although it was no more genuine than theirs. ‘There you go: if you couldn’t tell, how could we believe the word of any witnesses the court produces? Are there any witnesses?’

‘We’re not sure.’

‘I guess for their sake we have to hope there aren’t.’

‘That’s right, Christmas is a time when families should be together, not attending funerals.’

‘OK. Just out of curiosity, why did you kill him?’

‘Why not?’ said Meic.

‘Maybe we just didn’t feel very Christmassy,’ said Othniel.

‘Bah, humbug!’ said Meic and laughed. ‘And besides, don’t you hate they way they turn up earlier every year?’

‘The decorations in the shops went up in October.’

‘It’s certainly very irritating but I wouldn’t kill a man for it.’

‘Maybe we have a lower irritation threshold.’

‘Maybe. But I’m still not persuaded by your motive. I need more than that to give you those books.’

‘It’s all to do with a taxonomic problem we have,’ said Meic. ‘That means something to do with how you classify things, y’see. And as purists we’re a bit tired of Father Christmas being wrongly classified as a Christian icon.’

‘Wrongly expropriated, in fact,’ added Othniel.

‘You saying he’s not a Christian?’

‘No, we’re not saying that exactly. The name Santa Claus is derived from St Niklaus of Myra, in Asia Minor, a fourth-century Christian bishop. Now we got nothing against this chap—’

‘He once resuscitated three girls who’d been murdered and pickled in brine,’ said Meic.

‘Of course,’ added Othniel, ‘if he’d resuscitated some girls we’d pickled in brine we wouldn’t be very accommodating about that.’

‘When we pickle someone we expect them to stay pickled.’

‘Some people would call us old-fashioned.’

‘Although not to our faces.’

‘No, not to our faces.’

‘Tell me about the taxonomic problem.’

‘Santa Claus is an upstart. The real Father Christmas is the pagan god Odin who brought presents at the time of the festival of Yule, which celebrated the winter solstice, the death of the old year. The early Christians put their festival on the same date so that everyone could swap over without giving up their favourite rites.’

‘Which we don’t think is very fair on Odin.’

‘I can see why that would annoy you. Apart from wanting the books for your library, why are you telling me?’

‘So we don’t have to kill you, too.’

‘Do you have to kill me?’

‘If you stuck your big hooter in places where it had no business being inserted, and found some evidence that might be embarrassing to us in this connection, we would have to kill you, wouldn’t we?’

‘Not necessarily.’

‘Oh, believe us, we would.’

‘Would that be such a problem for you?’

‘It would be an unnecessary inconvenience.’

They stood up and left, adding, ‘And this is the season of goodwill.’

I think it was the second Thursday before Christmas when the woman claiming to be the Queen of Denmark called about the ad. It was one of those melancholy winter afternoons; the sky had that flat translucent greyness which filters through the window of the office like the glow you get from an old TV tube after it has been switched off. The sort of translucence that used to puzzle me when I was a kid and still had the capacity to stare in wonder at the sky. The sort of sky that communicates in some arcane way that snow is on the way. There is only one way to describe a winter sky like that. Plangent.