Dog Stays in the Picture (3 page)

Read Dog Stays in the Picture Online

Authors: Susan; Morse

It took the kids, Yolanda, and me months to settle back east before we could send for Aya and Marbles, a recently rescued kitten still in recovery from her own singularly Dickensian early life before the earthquake. We stayed with many kind friends and relatives, and everywhere we went, Ben and Sam managed to locate a couple of wrenchlike objects first thing, and they'd march around brandishing them, sternly repeating,

Gotta turn off da GAS, Mama!

The series of moves was particularly discombobulating for Eliza. In Philadelphia I tried settling her in a local Montessori school run by the Saint Joseph nuns, who promised an appealing mission of caring for the “Whole Family” in their brochure, and I found a posttraumatic-stress-type family therapist for support. It was rough goingâEliza was quite out of sorts, and I wasn't sure how to help.

One afternoon I left her sleeping in the car for a few seconds while I brought in the groceries. We were house-sitting at a home with a long driveway, sheltered from the street in a peaceful neighborhood. It was toward the end of a cold February; snow was still on the ground even though the day was sunny and the temperature seemed okay. (So I thought. I had not yet got the hang of things on the East Coast.)

When I went into the house, the phone rang. While I was answering I looked out the window to make sure Eliza was all right, and had to drop everything and make a dash for it. Eliza had woken up, the car was heating in the sun more quickly than I'd anticipated, and she was panicked, sobbing, and hyperventilating in the backseat.

Eliza was unusually clingy at school drop-offs after that, and I had an unhelpful tendency to linger till she was happy. The PTSD therapist instructed me to stay very calm, matter-of-fact, and not to be overly demonstrative when saying good-bye. This behavior did not come naturally to me. I really felt Eliza's pain, and wanted nothing more than to scoop her up and take her home with me. But I tried to be stoic, and Eliza's sweet, gentle teacher would watch us at the door, perplexed: Eliza begging me not to go, and me with my poker face, forcing out awkward reassurance, Robot Alarm Manâstyle.

(You will be. O-kay. I'll be back. Ve-ry soon.)

I don't think it was only earthquake trauma that made me so desperately attached to Eliza; it just made things more complicated. I'd been this way since her jaundice, and when I'd wrestled myself away and shut that schoolroom door I'd go home with an uneasy feeling. There was something about the look on that teacher's face. â¦

David was still filming in L.A. Yolanda had agreed to come with us and help out in Philadelphia, and she and the boys were getting along famously. I was making a special effort to give our traumatized daughter as much quality time as possible, and so we went to her school's Family Fun Day, just the two of us.

Eliza and I were sitting with our juice boxes on a little patch of grass, watching jolly children and their parents walking by. Out of nowhere this stern old nun I had never laid eyes on before stopped and said:

Hello, Eliza.

Eliza did not seem to know who this was, and I smiled. But the nun did not make eye contact with me at all, and disappeared into the crowd. That uneasy feeling again.

We'd moved to yet another post-earthquake temporary rental, a vintage

Addams Family

âstyle gabled Victorian, which usually served as our church's rectory, and David came home from filming. One afternoon a friend brought her three children over for an afternoon playdate, and the house was busy. At some point I happened to glance out a leaded front window, and paused to watch a sort of ordinary man with a clipboard ease tentatively out of his car and linger at the end of our front walk, gazing up at the façade. Jehovah's Witness, maybe? He seemed to be psyching himself up in exactly the way that banker with the briefcase used to screw up his courage before knocking on the Addams Family's front door. Long story short: it was Child Protective Services.

This was about the car episode. Eliza explained to me later that she had felt she needed a hug one day at school. She figured out she could have one if she told her teacher she was upset because her mother had left her in the car alone and it got really hot and she was sooo scared.

Ever since Eliza's outpouring, behind the scenes, her teacher began watching my weird Robot Mama routine at drop-off and scanned Eliza daily for possible bruises. She had mentioned something about Eliza's car story in a conference I'd requested, but it didn't occur to naïve me (or to the teacher, as she explained when I later called in a panic after Mr. Child Protector's visit) that the headmistress (the creepy old nun from Family Fun Day!) had decided to alert the state.

So now we had a new kind of danger to grapple with. This was my hometownâpeople knew me, sort of. But I was returning after more than a decade, with a new exotic identity: Wife of Movie Actor. Kurt Cobain had just died, and his wife, Courtney Love, was battling rumors of heroin addiction and trying to keep custody of their new baby. David and I were not interesting enough for the tabloids and never would be (thank God). But he was playing an ex-con in

The Crossing Guard.

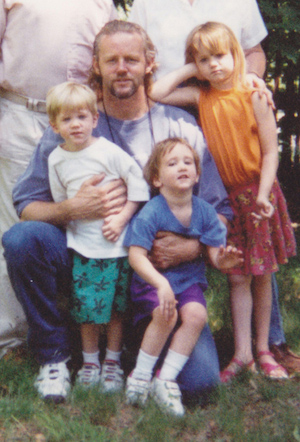

David prepares for his roles meticulously, so he had this fantastic new hard-earned prison-yard bodybuilder physique; he had grown his hair long and was keeping it slicked back in a greasy little ponytail; and whenever he turned up in our small, cloistered new neighborhood, people did not quite know what to make of him. Our family portrait was not looking exactly suburban.

David, Eliza, Sam, and Ben, 1994

Here the children were, just recovering from a natural disaster, supposedly safe, only to be possibly ripped from their parents and dumped in

foster care

?!

Mr. Child Protector turned out to be extremely good at his job, thank goodness. He talked to me and David, sniffed around our house a little, and took a few minutes alone with Eliza. Then he told us this was the most pleasant assignment he'd ever had (it was quite a novelty to evaluate a wholesome family for once, he said), and our slate was wiped clean as if nothing had ever happened.

I ran into Eliza's old teacher at the market some years later. We had a good talk, and I told her Eliza was happy in her new school, much more settled. She said things were a lot better for her students, tooâthey had replaced that creepy nun, their headmistress.

The first weekend I ever dared leave our kids was the following year. David had been nominated for an award for

The Crossing Guard

,

and the producers flew me out to meet him in L.A. for the ceremony. I lined up the children's favorite, most responsible sitter, an assistant DA paying off law school. Eliza had a really hard time going to bed the night before I left, so we did not get much sleep, and I was in a bit of a daze getting on the plane. There was heavy turbulence midflightâlong periods of shaking, the hammering kind where lights flicker and flight attendants take to their seats. Like the improbable threat of earthquakes, turbulence BC had never bothered me much. But on that first solo flight since the kids were born, I sort of snapped:

Who will take care of them if I crash?

I know you're not in any real danger in turbulence, but I simply could not get it togetherâ

Okay, so I'm not going to crash but what about the next time I have to fly with the kids and we have bumps like this and they are a little scared? What if I make it even worse because I am freaking out myself? We'll never be able to visit David on location, the children will not have a relationship with their father, and he will divorce me because we never see each other, and basically the world as we know it is going to end because I can't keep collected on a bumpy flight!

I was so desperate I picked up the air phone under my tray table and called my mother, of all people. For once, I did not object when she suggested we recite the Lord's Prayer together. (The woman sitting beside me, who did not seem even slightly alarmed by the bumping, acted as if nothing was happening.)

I am not a prescription-drug-type person, but since then I've always flown with anxiety meds. They work! When the bumps start, all I am aware of is distant muffled screamsâa lunatic lady locked in some secret, padded compartment deep inside my psyche, screeching and wailing. I feel completely at ease. I just smile sympathetically and think,

Poor woman. So glad that's not me.

Another item I'd definitely have in my iPod for help with those acting preparations: the soundtrack of

Mamma Mia!

This is very serious stuff. I am about one-quarter Swedish, and I should know. Those ABBA Swedes have soul.

Halfway through middle school I finally began to believe that Eliza had truly found her independence. The penny drop may have had something to do with the difference in protocol between lower and middle school. In lower school you could walk your child into homeroom, and most people did. Since homeroom drop-off was an option, there was no question: I was of course going to park the car and go in with my daughter. (If sitting in the classroom breast-feeding your eight-year-old on your lap all day had been an option, I would have seen it as my duty.) I never did get the hang of that lower-school drop-off technique, so when David was at home, that was his job, and he was a lot better than I was at separating calmly with Eliza in the mornings. I dropped the boys off. The boys did not give a rat's ass

who

dropped them off, or even where. They had each other, so there was never an issue. Maybe God saw how badly I was muffing it with Eliza and gave us twins to save everyone a little stress.

By middle school, with the help of wonderful Ms. Tinari and Ms. Ferguson in their full-length down coats, smiling and dancing from one foot to another for warmth at the frosty curb every morning, Eliza and I finally learned to release with dignity. Eliza would hop out and trot gaily up the steps. I would be okay, I guessed. By the end of eighth grade I'd only occasionally linger to watch her pink backpack disappear through the glass doors before I'd well up, and have to gulp it back on my way up the driveway.

She's growing up fast. â¦

By the spring of that last middle-school year she had a boyfriend. Eliza was thirteen, and being seen places with her mother was becoming a bit of an embarrassment. But she was forced into my company one evening in order to satisfy a requirement: Eliza had to attend a music concert of some kind, and write a paper about it. A Broadway musical seemed like the least painful outing, and the only touring company in Philly that spring was

Mamma Mia!

We knew nothing about it. I had totally missed ABBA in the '70s, but my sister Colette, who is British and very cutting-edge, claims that their harmony is on the level with Bach or something crazy like that, and their material can be surprisingly primal, as well. For the uninitiated: ABBA was made up of two married couples. The name is a sort of anagram because both women's names begin with an “A” and the men's begin with a “B.” When the first “AB” pair divorced, they managed to keep the group together for a while. Some of the songs they wrote and performed toward the end were intensely personal, illustrations of the turmoil they were going through in their relationships: Picture A, belting out her anguish over B's infidelity, while B, who actually wrote the song, is onstage playing backup. I was intrigued.

During the first act, I think Eliza was too cool for school, attitude-wise, and to be honest, I was as well. I wanted to keep my mind open, but we both felt out of our element and were having a sort of reverse mother-daughter bonding experience, both of us rolling our eyes at all the screaming middle-aged women around us leaping to their feet for the climactic dance numbers.

Platform shoes and glitter Spandex!

So I was not expecting to be blindsided in Act II. There's a heartfelt, simple ballad, “Slipping Through My Fingers,” where the central character (the Mamma) is helping her daughter into her wedding dress, reminiscing about how it felt to watch her “funny little girl” leave home with her schoolbag in the early morning.

Sitting in the dark, surrounded by sniffling menopausal women, next to my own funny little girl on the eve of high school

(The driver's license! The college applications!),

the song ripped me right out of my snarky attitude into a deep place; I was jettisoned instantly back to my minivan in the school drop-off lane, watching that pink backpack bob eagerly up the steps. Tears streaming, nose running, all the while desperately keeping my head as low as possibleÂ, trying to conceal my sudden ABBA conversion from Eliza, because if she realized I'd been sucked in like this she would either be mortified, or worse, fall apart herself.

I am beginning to sense I'm not the only hysterical helicopter in the box. I have companyâmy friend Susan, with her earthquake-kit milk letdown, for one, and these ABBA ladies, with their hot flashes, whimpering next to me in the dark. I really felt a connection with the ABBA ladies that night, and if Eliza hadn't been there I probably would have joined the Conga line they formed up and down the aisles of the Shubert Theatre for the grand finale.

(Waterloo!!!)

And then I'd have taken these new sisters of mine out for coffee and asked the million-dollar question: What's this primal thing that bonds us to our kids? And what's the shift we're makingâthis shift from worrying we'll die and leave our children defenseless, to despairing because they're not going to need us anymore?