Dog Sense (7 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Putting aside these objections about popular conceptions of wolf hierarchies for a moment, we should note two further reasons why understanding wolf behavior cannot be the be-all and end-all for understanding dog behavior. Scientists have (inadvertently, to be fair) studied the wrong wolves (on the wrong continent) and ten thousand years too late.

The American timber wolf, which is a sub-species of the grey wolf, is the most studied wolf of all and has long been used to interpret the behavior of dogs.

7

Until very recently, researchers tacitly assumed that the American timber wolf was closely related to the domestic dog and, therefore, that studies of American wolves were highly relevant to understanding what makes dogs tick. However, the advent of DNA technology has forced a reappraisal of this comparison between dogs and American timber wolves.

Apart from deliberately bred wolf-dog hybrids, it has not been possible to trace the DNA of any of the dogs in the Americas to North American wolves, not even the “native” dogs who were there before Columbus. This lack of evidence has not been for want of effort. The first such genetic analysis was done on the Mexican hairless dog, or xoloitzcuintli. The Spanish conquistadors discovered this dog when they first arrived in Mexico, where it was used for a variety of purposes, including companionship and food; it was also believed to have healing powers. To avoid contamination of these supposed properties through cross-breeding with European dogs, xolos were reportedly bred secretly in isolated locations dotted throughout western Mexico, and their descendants survive to this day. Could these dogs be relics of an ancient domestication of New World wolves? Their mitochondrial DNA (inherited through the female line) proves otherwise: It is most similar to that of European dogs (and wolves), bearing no resemblance to that of American wolves.

Although the xolo's genetic makeup suggests that this dog originated in Europe, not South America, it is possible that the American continents produced other native dogs. Indeed, the modern xolos examined by scientists might conceivably not have belonged to an ancient breed at all but, instead, may have been facsimiles re-created by breeders from crosses between European breedsâa possibility that would explain why the modern xolos' DNA is European in type. So genetic researchers next turned their attention to DNA extracted from the marrow of dog bones more than a thousand years old taken from archaeological digs in Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia, as well as to DNA in the bones of dogs buried in the permafrost of Alaska, prior to the discovery of that area by Europeans in the eighteenth century. In both cases, the DNA was much more similar to that of European wolves than to that of American wolves.

While research into the origins of modern dogs is far from over, the available evidence makes it clear that comparisons between domesticated dogs and American timber wolves should be treated with caution, to say the least. And in any case, since the research has thus far focused almost entirely on maternal DNA, the descendants of a mating between a male American wolf and a female domestic dog would not have been picked up. Some American dogs may therefore carry American wolf genes from one or more long-distant male ancestors; research should be

able to resolve this soon. What is clear, however, is that no female American timber wolves were successfully domesticated. It is impossible to determine, thousands of years after the event, whether the reason for this outcome is that American wolves were intrinsically difficult to domesticate or that the first human colonizers of the Americas, having brought their own dogs with them from Asia, saw no need for further domestication. Rather, being hunters, they would have perceived the local wolves as competitors. Whatever the explanation, the fact remains that the vast majority of domestic dogs are only very distantly related to the American timber wolf, separated as they are by a hundred thousand years of evolution. This is why comparisons between wolf behavior and dog behavior need to be treated carefully: Most studies have been done on a type of wolf that, if it was any more distantly related to domestic dogs, would probably be considered a different species.

Skepticism about comparisons between wolves and dogs is further warranted by the fact that, although DNA analysis indicates that dogs descended from Eurasian grey wolves, none of the wolves that have been studied over the past seventy years or so, American or European, can possibly be considered the

ancestors

of the domestic dog: The two certainly had a common ancestor many thousands of years ago, but there is no evidence to suggest that modern wolves closely resemble these common ancestors. Indeed, logic dictates precisely the opposite.

Wild wolves, as they exist today, are almost certainly quite different in behavior from theirâand dogs'âancestors. As soon as agriculture began in earnest, all wolves that had not been domesticated would inevitably have become a threat to the newly formed herds of livestock, and so they would have been persecuted by humans. Until firearms became widely available in the eighteenth century, human efforts to eradicate wolves were fairly ineffective, but thereafter it became possible to exterminate wolves from whole areas. For example, the wolf population in Norway and Sweden declined dramatically from the 1840s onward; the DNA of today's Scandinavian wolves shows that they are descended from immigrant Russian animals, which had hung on in isolated areas throughout the twentieth century, until the modern conservation movement gave them the space to move into areas recently vacated by their cousins. This pattern of local extermination, or at least severe population reduction, was repeated throughout Europe; the few wolves that survived must inevitably have been those that were the most wary of people. Today's wolves are therefore the descendants of the wildest of the wild, whereas today's dogs must be derived from a much more tameable sort of wolf, one that is no longer found in the wild and about which we know almost nothing.

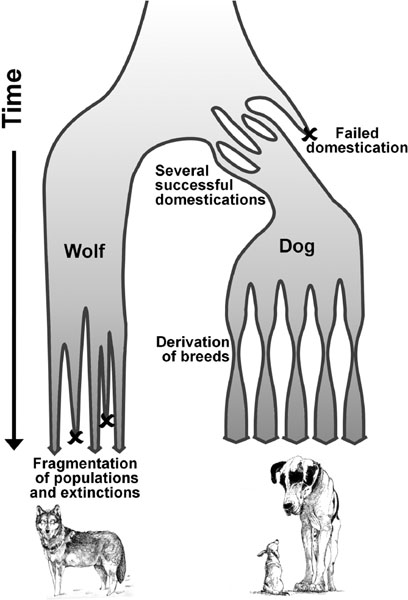

A simplified representation of the evolution of the wolf and the domestic dog. Genetic “bottlenecks” occurred at each of the domestications (one failed domestication is shown); when dogs were divided into breeds; and when many local wolf populations went extinct, leaving the survivors isolated from one another in different parts of the world.

So, although the DNA of dogs tells us that they are indisputably wolves, much of the scientific study of wolf behavior conducted in the twentieth century must now be regarded as of dubious significance to our conception of dog behavior. Most of the wolves that were studied were kept under conditions that we now know were not just highly artificial but also highly stressful for many of the individuals concerned, thereby inducing highly abnormal behavior. Furthermore, we have no reason to suppose that any of these wolves precisely resemble the type of wolf that was originally domesticated. Such wolves no longer exist; they are far from extinct, since they have millions of living descendantsâour dogsâbut they no longer exist in the wild. Their nearest wild equivalents are probably feral dogs, domestic dogs that have reverted to a wild or semi-wild existence; these, too, are the direct descendants of the wild ancestor of the dog, and they live a similar, independent lifestyle.

Since comparisons with the wolf are no longer as valid as they seemed as recently as a decade ago, my approach is to widen the search for the biological characteristics that make up the dog's true nature. Some of the characteristics that enabled domestication may indeed be much more ancient even than the wolf, going back many millions of years to long-extinct species that were themselves the ancestors of wolves, jackals, and wild dogs. All of these current species have features in common, features they most likely share with their common ancestors: They live in family groups (where young adults often help their parents to raise the next round of offspring), have excellent noses, are highly intelligent and adaptable, and are either hunters or scavengers or both.

Ultimately, there may be nothing special about the wolf that singled it out for domestication; perhaps it just happened to be the social canid that was in the right place at the right time.

8

Unfortunately, both that

place and that time are currently shrouded in mysteryâbut what is certain is that the aberrant and atypical behavior of modern, captive wolves is highly unlikely to be of any value in understanding either the behavior of these ancestral wolves or that of domestic dogs. Rather than focusing exclusively on the grey wolf, we should regard the dog as a canid whose closest living relative happens to be a wolf. It is the possession of the canid toolkit that was vital to the successful domestication of the dogâa story whose roots are intimately entwined with those of our own.

How Wolves Became Dogs

T

he story of the dog's domesticationâits evolution from wolf to its own unique sub-species of canidâparallels that of our own emergence into civilization, from the hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic through to the modern age. There were domestic dogs well before any other animal was domesticated, so arguably the dog is likely to be more altered relative to its ancestors than any other species of animal on earth. The process of domestication has stripped away much of the detail of the ancestral species, but dogs nonetheless retain some of the characteristics of the more ancient lineage that gave rise to dog, jackal, coyote, and wolf alike. Dogs are somewhat like each one of these, but they are also unique, the only fully domesticated canid, and much of what makes them unique was introduced by that very process of domestication. The story of that domestication therefore makes an essential contribution to our understanding of what our dogs areâand what they are not.

Over the last decade we have learned a great deal about the domestication of the dog. The sequencing of the DNA of hundreds of individual dogs has forced a reappraisal of previous data regarding the process of domestication. While there are undoubtedly more surprises to come, the broad scope of how it happened as well as much of the detail are now fairly well established.

In addition, we have new perspectives on when and where the dog may have been domesticated. We can be reasonably sure that there were several, possibly many, attempts at domestication of the grey wolf, in

various parts of the world, but also that the products of some of those domestication eventsâin places other than North Americaâultimately endured whereas others did not. The process of discovery is still ongoing; ancient bones and fossils that were formerly identified as unequivocally belonging to wolves are being reexamined, in case they might actually have come from early wolf-like dogs. The evidence has been clear enough, however, to place the separation between wolf and dog further back in their evolution, by thousands of years, giving more time for wolf and dog to divergeâan analysis that further undermines the idea that the behavior of the dog is simply a subset of that of the wolf.

While we are gaining a better understanding of the ways in which dogs are different from wolves, we are also learning more about how we, as humans, have helped to make the dog different. The domestication of dogs has been revealed as a complex process, more convoluted than that of any other animal, leading not only to radical changes in the shape and size of their physical bodies but also to an almost complete reorganization of their behavior. Furthermore, while humans have guided that process, it is only in the past century and a half, and only in the West, that we have taken control of it completely. For ten thousand years or more, as the purposes for which dogs were valued changed and proliferated, dogs have coexisted and coevolved with us. Essentially, they domesticated themselves as much as we domesticated them.

When was the dog domesticated? Until fifteen years ago, the answer was thought to be simple. The oldest remains of dogs found by archaeologists were carbon-dated to be no more than twelve thousand years old, fourteen thousand at most. This timeline placed the first dogs before the beginnings of agriculture about ten thousand years ago, and well before the domestication of any other animal. So the dog was, for this reason alone, considered a special case: the pioneer for all subsequent domestications, such as goats, sheep, cattle, and pigs. Because it was domesticated so early in the history of humans, there is little detailed evidence as to how wolves became dogsâa paucity of information that has left a great deal of room for speculation as to why and where this first occurred. Until fifteen years ago, however, at least the “when” seemed well established: No bones had been found that both unequivocally belonged

to a dog and were more than fourteen thousand years old, so domestication must have occurred no earlier than about fifteen thousand years ago.

Then, in 1997, a team of scientists from the United States and Sweden made an astonishing claim: They had sequenced DNA from living dogs and wolves, and the findings indicated that domestication could have taken place more than a hundred thousand years earlier.

1

If this was true, it would mean that dogs were man's companions not just at the birth of agriculture but right at the dawn of our own speciesâas soon as modern humans had emerged from Africa, where they had evolved, and encountered grey wolves (which do not occur in Africa) for the first time. This announcement triggered a minor epidemic of speculation about the possible coevolution of man and dog. Most archaeologists rejected the idea, pointing to the complete lack of dog remains that could be dated any earlier than fourteen thousand years ago. But there was nothing intrinsically wrong with the DNA data, even though its interpretation was still open to debate. Dogs, it seemed, joined us during our pre-agricultural origins.