Dog Sense (36 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Dogs playing with a tug-toy are actually competing

In short, dogs appear to be in a completely different frame of mind depending on whether they are playing with a person or with another dog. When the play-partner is a dog, possession of the toy seems to be most importantâand, indeed, it's possible that competitive play is one way that dogs assess each others' strength and character. (For dogs, these games are primarily a way of assessing resource holding potential.) When the play-partner is a person, however, possession of the toy seems irrelevant; the important thing is the social contact that the game produces. This finding is entirely compatible with the observation that dogs can't calm one another down but can be calmed by their owners. It also indicates that dogs put humans in a completely different mental category from other dogs.

This distinction between play with people and play with dogs is not confined to Labradors but, rather, appears to be a universal attribute of

domestic dogs. As part of the same overall study, we also surveyed dog ownersâand observed them with their dogsâto determine whether play with people interferes with play with other dogs. We hypothesized that if the two potential playmates were interchangeable as far as the dogs were concerned, playing with a person should diminish their appetite for playing with other dogs and vice versa. But we saw no evidence for this at all: When watching owners playing with their dogs off-leash in parks, we found the quality of play to be the same whether the owner had one dog or more than one. In a related survey, we asked 2,007 owners with only one dog and 578 owners with more than one dog how often they played with their dogs, and we discovered that the owners with several dogs actually played slightly

more

with each of their dogs than did those with only one. Although it was impossible to record the quality of the play, we concluded that most dogs are very happy to play with their ownersâwhether or not they have a canine alternative. Again, this suggests that dogs' minds have separate categories for “people” and “dogs.”

Play between dog and owner is such an everyday occurrence that it's easy to lose sight of the fact that inter-species play is otherwise very rare (indeed, virtually unknown outside the realm of domestic pets). To be successful, play requires well-synchronized communication; both partners must be able to convey their intentions precisely while at the same time convincing each other that they're not using the game as a prelude to something more serious, such as an actual attack. The rarity of such play is probably accounted for by the limitations of communication between members of different species.

The capacity of dogs to engage in play with humans is particularly surprising given the sophistication of dog's communication with other dogs during play. For instance, when two dogs are playing together, play-bows are much more likely to occur when they are facing one another than when one is facing away, indicating that dogs are sensitive to whether or not their play-partner is paying attention to what they're trying to convey.

19

Dogs that want to perform play-bows but are being ignored have a variety of ways of getting another dog's attention, including nipping, pawing, barking, nosing, and bumping. Humans are much less clever at this than they are, so the boundless appetite that most dogs seem to have for

games with their owners, and even with people they don't know so well, must be due to the strength of their attachment to mankind in general.

Play-bow

However, our knowledge of dogs' cognitive abilities gives us no basis for thinking that dogs are aware of what they are doing when they are playing in the same way that we are aware of (and so can talk or write about) how we play with a dog. Dogs may appear to “deceive” their human play-partnersâfor example, by dropping a ball and then grabbing it again before the person has time to pick it up. But there is a much more straightforward explanation for this behavior: We know that dogs find play rewardingâ“fun”âand since it takes two to make a game, any sequence of actions that happens to stimulate play in others should quickly become part of the ritual that that dog and person engage in whenever they play, by simple association. Thus in this instance the dog must have accidentally dropped a ball when near a person in the past, and then quickly grabbed it again (as a wolf would do if it accidentally dropped a piece of food). And with its priorities focused on human reaction, it must have noted the person's excited reaction to this apparent “deception.” Therefore, it will repeat the sequence of actions in the hope of getting the same reaction againâwhich of course is likely to happen.

Indeed, although we humans are undoubtedly less good at interpreting dog behavior than another dog would be, dogs are uniquely so focused on the reactions they get from people that they are able to adapt their behavior to fit our own. I don't mean that they do this consciously; rather, my point is that our behavior comprises the most salient cues available to them, such that, without having to think about it, they can adjust their reactions to us using quite simple associative learning.

Many dogs are friendly toward people in general, but it's obvious that they all know the difference between strangers and familiar people and between individual people that they know well. So far, science has only just begun to investigate how dogs tell people apart from one another. Evidence suggests that they build up a single, multisensory “picture” of people they know: In one study, researchers played for dogs a recording of the voice of one person they knew but then showed the dogs a picture of someone else they knew. The dogs gave a look of surprise, as if the voice had already conjured up the face that should go with it. (In addition, there is probably an olfactory dimension to the picture that dogs create of usâa dimension about which we ourselves are largely unaware.)

Dogs are also very sensitive to what goes on within relationshipsânot just those in which they're directly involved but also those they observe between people. In one recent study, a dog was allowed to watch three people performing a scripted transaction.

20

In this exchange, one person acted as the “beggar” and each of the others either gave him the money he was asking for (this was the “generous” person) or did not do so (this was the “selfish” person). Once the beggar had left the room, the dog was released and allowed to interact with the other two people. The dogs preferred to interact with the “generous” person; most went to her first and chose to spend more time interacting with her than with the “selfish” person. It seemed to be the actual act of handing over the money that was important to the dog, because when the whole scenario was repeated but with no beggar present (meaning that the transaction had to be mimed), the dogs showed no preference for the “generous” person.

Dogs also demonstrate some understanding of relationships between people and other dogs in the household. In an experiment designed to

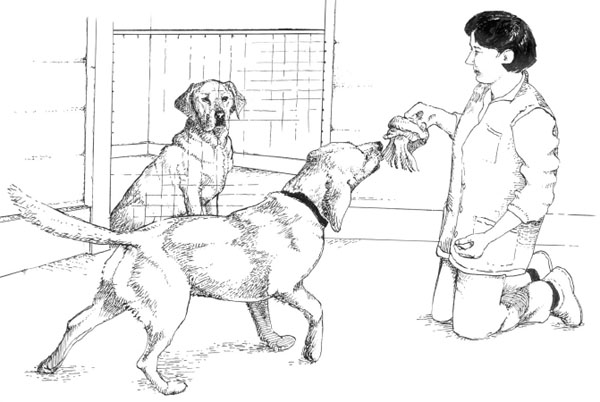

verify this, a Labrador was placed on one side of a transparent gate and allowed to watch tug-of-war games between a person and another Labrador.

21

Unknown to either of the dogs, the games were manipulated so that during some trials the person always won possession of the tug and during others the dog was allowed to win. Furthermore, some of the games were made “playful” (the person performed play-signals) while others were made “serious” (the person did not perform such signals). After the game, the spectators were let out from behind the gate where they had been watching. After “playful” games, the spectators preferred to interact with the apparent “winner,” whether dog or person; after “serious” games, the spectators were reluctant to approach either dog or person. Thus dogs don't just react to dogs or people as individuals; they also react to what they've seen go on between them. However, this is not to say that they necessarily understand what the concept of a “relationship” is. More likely, they simply modify their behavior toward each of the participants depending upon what they've just seen them do.

The dog behind the barrier is watching a game of tug between a person and a second dog

If I've given the impression that I'm trying to portray dogs as just “dumb animals,” it's the wrong impression. I know they can be very smart, but in their wayâand not necessarily in our way. One problem with much of the research on canine cognition is that there is always an implicit comparison with our own: With what children's age are dogs comparable? Can dogs learn human language? And so on. The question that remains is this (and it would be a very difficult question to even begin to answer): Do dogs have cognitive abilities that do

not

have any direct counterpart in our own? For example, we know that their sense of smell is much more powerful than ours. Are they perhaps capable of processing the information they gather through their noses in ways that we do not yet understand?

Emotional (Un)sophistication

D

ogs are smart when it comes to learning about things, people, and other dogs. Nevertheless, they have their limitations. Their lack of self-awareness, their lack of awareness that we have minds different from their own, and their inability to reflect on their own actions all restrict their capacity to comprehend the world in the same way that we humans do. Furthermore, because of such limitations, dogs' emotional lives are likely to be much more straightforward than our own, meaning that they may not be capable of feeling many of the subtler emotions that we ourselves take for granted. Nevertheless, dogs share our capacity to feel joy, love, anger, fear, and anxiety. They also experience pain, hunger, thirst, and sexual attraction. It is thus perfectly possible for humans to both understand and empathize with what they are feeling. Yet this facility is also a trap. It can seduce us into presuming that dogs' emotional lives are identical to oursâthat in any given situation (as we see it) they are feeling what we would feel. In such instances we are drawn into acting accordingly, treating our dogs as if they had exactly the intelligence and emotional capacities that we do. Since this is not the case, our actions may be meaningless to the dogâor, indeed, may mean something quite different from what we intended. Hence a thorough understanding of the full emotional capacities of dogs, and which of these capacities are simpler than our own, is essential to their well-being and to the integrity of our relationships with them.

One notable difference between dogs' emotional lives and our own is that their sense of time is much less sophisticated. Their ability to think back into their past, to mull over what has happenedâeven quite recentlyâand make sense of it, seems almost nonexistent. Dogs are therefore much more inclined than we are to draw cause-and-effect conclusions based on the occurrence of two events one immediately after the otherâeven when a moment's reflection, if only they were capable of such a thing, would make it obvious that such a connection was unlikely. Dogs don't “do” self-reflection.

But the mere fact that dogs lack the level of consciousness that we have does not mean they lack rich emotional lives. The science of canine consciousness is still in flux, but the current consensus is that dogs possess some degree of consciousness. In other words, they are probably aware of their emotions, but to a lesser extent than humans are. Scientists generally agree that our consciousness is much more complex than that of other mammalsâin part, owing to the massively larger neocortex in the human brain as compared to that of mammals like dogs.

1

Indeed, we humans are able not only to experience emotions but also to examine them dispassionately, to ask ourselves questions such as “Why was I so anxious last week?” Dogs seem to be incapable of this kind of self-awareness. All of the available evidence suggests that their emotional reactions are confined to events in the here-and-now and involve little, if any, retrospection.