Dog Diaries 07 - Stubby (6 page)

—

In our new camp, the soldiers learned all kinds of things. They got lessons every day from a bunch of French soldiers. Our boys learned to build barracks in the field. They learned how to read French maps. They practiced how to operate machine guns. These are big guns that make an

ack-ack

sound that’s hard on a dog’s ears. They also learned to toss grenades without blowing themselves to bits. Grenades are metal things that look like small

footballs. I watched one day as Conroy pulled the ring out of the top of one, counted to five, and then tossed it. A moment later, there was a gigantic explosion. Some football! But the men spent most of their days learning about trench warfare.

What was trench warfare? It doesn’t exist today. But that was mainly how war was fought in Conroy’s and my time. A trench is a long, narrow hole in the ground. First the men poked around to find good, dry dirt to dig in, so their trench wouldn’t fill up with water. Now a dog would never have to

learn

how to dig a proper hole. We are born knowing how, with paws that are built for digging. We dig holes to sleep in, to bury stuff in, and sometimes just for the sheer joy of digging. But for men? It’s work. And it’s a skill they have to learn.

In the gear the soldiers carried strapped to

their backs was something called an entrenching tool. This is a fancy name for a shovel. Not being blessed with paws, the men needed shovels to dig the trenches. These trenches were deeper and wider than any dog had ever dug—as deep and wide as a man is tall, sometimes even wider. And the trenches didn’t run in straight lines. They zigzagged all over the place so the enemy wouldn’t know where they were.

After the trenches were dug, the men lined the top edges of them with sandbags. These were supposed to stop bullets from going into the trenches. Good idea, right? Then the soldiers set up camp in the trenches and made themselves at home. Imagine! Men living in burrows like packs of wild animals. That’s war for you. They slept there, ate there, yammered there, did their business there, and read letters from home there. Every day, they practiced

crawling up to the top of the trenches behind the sandbags. They rested their guns on the bags and fired them. Sometimes the bugler sounded a call and they went charging over the tops of the trenches, hooting and hollering and firing away. Between hooting and hollering, rifles blasting, grenades bursting, and machine guns

ack-acking,

there was a regular racket going on. It’s a good thing I’d gotten used to the noise back in New Haven. Otherwise, I’d have headed for the hills on day one!

Mornings and nights, the soldiers chowed down on rations. Rations were what they called the food that was stored in tins and boxes that the government handed out. It wasn’t always the freshest stuff, but it kept us going, and I, for one, couldn’t get enough of it.

Like all the soldiers, Conroy carried a haversack. In it, there was a plate, a cup, a knife, a fork, a

spoon, and the all-important (if you ask me) meat can. There was almost always something good in the meat can. Naturally, Conroy shared it with me. Afterward, he poured water from his canteen into his cup, and I lapped it up. Living in a trench made you thirsty. At night, the soldiers sat around and talked in soft voices, even though the enemy was far away. They were practicing being quiet.

Shhhh.

“When are they going to send us to the Front?” one of Conroy’s buddies complained.

“Quit your bellyaching,” another soldier told him. “We’ll be risking our necks soon enough.”

From what I had come to understand, this war had been going on for a good three years, since before I was even born. So far, it had just been the English and the French fighting against the Germans and a bunch of other guys. And it looked like the Germans and their friends were winning. That

was because they had more men and bigger guns—like the one they called Big Bertha. We Americans were Johnny-come-latelies, pitching in now to help the English and the French.

The French soldiers teaching the Americans were hardened by their time fighting. I could tell they didn’t think much of our boys. In fact, these Old Sweats—as experienced soldiers were called—thought the American Expeditionary Forces were a bunch of green lads.

Green

means inexperienced and ignorant. Much as I hated to admit it, they might have had a point. The Americans looked like fresh-faced kids. Next to them, the Old Sweats looked ancient. I felt sorry for all of them—the Old Sweats because of what they’d been through, and my boys for what they were about to go up against.

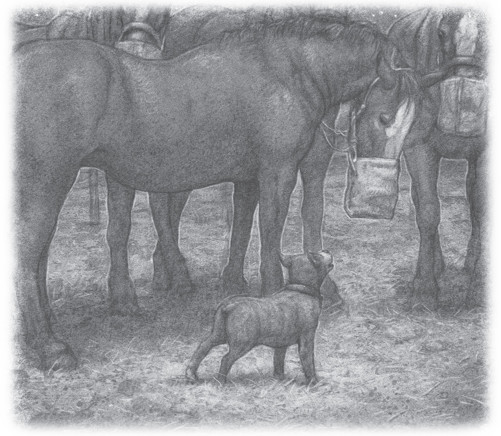

Nights, I got a little restless, and I would climb

out of the trench and go exploring. In my wanderings one time, I ran into a surprising number of horses. They stood around with their feed bags tied on, munching away.

Sidling up to one of them, I asked,

What’s a nice horse like you doing in a place like this?

The horse stopped munching and gave me a look. Then he went back to his oats.

He was a tough old boy, not all that friendly, the kind who did his job and minded his own business. Still, I wanted an answer so I kept at it.

So, buddy, tell me, how did you get here?

The horse probably figured I wasn’t going away until my curiosity was satisfied. He said,

If you must know, I was drafted by the quartermaster’s office. I was a farm horse in Iowa. I pulled a plow and minded my own business. Then one day a man came along and took me away from my family. He shipped me overseas, and I’ve been here ever since, serving good old Uncle Sam. There are thousands of us who were taken from our paddocks and stables and brought over here.

Now I got it! When I was a small pup, the streets

of New Haven were full of horses pulling carts and wagons. Then one day, it seemed like they all disappeared. I’d wondered where they’d gone to, and now I knew. They were here!

Have you been to the Front?

I asked. I was dying to hear more about it.

Plenty. At the start of the war, the soldiers rode us up there in cavalry charges. But we never stood a chance against those big German guns. They mowed us right down, man and horse. Now we go up there to haul supplies to the men in the trenches: rations and ammunition and artillery, medical and building supplies, and tons of mail. The cavalry days are over. It’s all about trench warfare these days.

Tell me about it,

I said.

I’ve worn my nails down to the pads digging trenches.

You’ll be digging more before your hitch is up,

said the horse.

I don’t mind. I’ve lived in worse places,

I said.

Wait until you get to the Front. When the enemy starts bombarding, you won’t think those trenches are quite so cozy. I’ll be getting back to my feed now. You watch out for yourself. The battlefield is dangerous. It’s no place for a little dog.

Don’t worry about me,

I said.

I was a street dog. I can take care of myself.

Sure you can, tough guy,

said the horse, going back to his munching.

I could tell he didn’t believe me. One thing was for sure: this horse had given me some things to think about. Like,

what have I gotten myself into?

As I turned to go back to the trenches, the horse called out to me,

And for pity’s sake, whatever you do, watch out for the gas!

Gas? What was gas? And why in the world did I have to watch out for it?

D

OUGHDOG

After five months of itching to see some action, word finally came down—we were moving to the Front. And just like that, all the cheerful chatter stopped. The men fell silent as they packed their gear. This was it. Real war, not just practice. We were going to a place called Chemin des Dames (shih-MAN day dom). That’s French for

road of the ladies.

As we made our way there in the bitter cold, we saw the damage that war had left in its wake.

Everything that was once living and green had been scorched to cinders, leaving a sea of mud. The soldiers slogged through it up to their hips. For a dog with stubby legs, it was nearly impossible. Conroy heaved me over his shoulder and carried me. Now and then, we’d hit dry stretches. He would set me down and let me walk.

Whenever we passed field hospitals, the wounded soldiers would rear up on their cots and call out to us.

“Good luck!”

“God help you!”

“Leave the dog with us. We’ll take care of him!”

“Don’t worry. So will I!” Conroy told them as we marched on.

We made our way past bombed-out buildings, wrecked wagons, dead horses, and whole forests of blackened trees. And of course, more mud.

“I know it looks bad,” Conroy told me, heaving me back up onto his shoulder. “But we’re in this together.”

It’s you and me, doughboy,

I growled, and licked the flour off his chin.

Doughboy. That’s what they called the American soldiers. No one was sure why. Maybe because the men were given flour to bake their own biscuits? My boys weren’t exactly bakers. The flour got all over them, and me, too. I had to wonder, did that make me a doughdog? Sometimes they called us Americans Sammies, as in Uncle Sam.

We, on the other hand, called the British soldiers Tommy, the French soldiers Frogs, and the German enemy Jerry. Why? I hadn’t a clue. Maybe it cheered the men up to call people names. But I didn’t care for it. Even when I lived on the street, where things got pretty rough, I never went in

much for name-calling. When it came to cheering people up, I did my bit, fair and square. I wagged my stub of a tail and tried to keep a wide grin on my chops at all times. So far, that was my biggest contribution to the war effort.

When we got to Chemin des Dames, the soldiers took out their entrenching tools and started digging. After the men were settled in, I ran all along the trenches, making sure everybody was safe. The soldiers saw me and grinned, their teeth bright in their muddy faces. By then, everybody in the unit knew me. When they called my name, I stopped to say hi and to give them a chance to scratch my back. By the time I returned to Conroy, I saw that he had dug a hole in the side of the trench. Good man! It was called a dugout. This was where we would bed down.

Things were trench-normal for the first few

days. That’s army-talk for Quiet with Nothing Much Going On. Then one day, out of the blue, the enemy attacked. Machine guns

ack-acked.

Bullets whizzed overhead. Mortar shells exploded. The sky turned dark and oily with smoke. Between the shells exploding and the artillery pounding, it was enough to make my head burst. This was definitely not what I’d had in mind the day I followed that army truck out of town. But I was determined to make the best of it.

“Stay down, Stubby, or you’ll get your head shot off,” Conroy warned me. He didn’t have to tell me. Seeing as how I was fond of my head, I lay low when the bullets flew.

Conroy and the other soldiers lay on their bellies behind the sandbags and shot back at the enemy. The bags jumped when bullets hit them. Bullets pinged off the soldiers’ metal helmets.