Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (42 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

Right after that video we had a number one single. What are the fucking chances? Well, I kinda sorta knew we would. Later that fall I ran into the Bitch Goddess of

Billboard

at a convention in the Bahamas. “What are you looking so glum for, baby?” she asked with a crooked smile. “Didn’t you get your number one with a bullet?”

“Are you kidding? That stuff with the ACL, that wasn’t funny,” I said.

“Ah, well, honey, we all gotta pay our dues,” said she. “And by the way, baby, there just might be a little more of that to come.” Before I got a chance to ask her what she meant, she’d vanished.

Got home, had to ice my knee another week before I went in for the operation. And when I came out of

that

wormhole, it was pretty fucking paralyzing—even though they did it arthroscopically. That means they drill a little hole in your knee and go in with a scope so they can see inside. They fill the inside of your knee with water, then flush it out so they can observe what’s going on in there with a miniature camera. On the camera are little scissors and they cut the ends of the ACL off—it looks just like spaghetti.

They take out your torn ACL and put in someone else’s; it’s called an allograft. When they take the ligament out of your other leg, that’s called an autograft. I said, “Fuck that, pass the cadaver, doc. I’m a creature who lives onstage, I need

both

legs, and I need all the help I can get.” He said, “Well, we got a freezer in the other room full of knuckles from people who died, and we can use ligament from one of those, because knuckles are like ACLs, they take little blood supply, and you don’t have to worry about rejection.” So they cut a ligament from this sixteen-year-old kid’s knuckle and used that to replace the ACL in my knee. Every night when I say my prayers, I say them twice and I thank that kid who gave me the ligament for my knee.

Got home the first day after they screwed my new ACL in and iced it. Second day, I get into this machine. You Velcro your foot into it, it has a slow-moving motor that moves your foot straight out, and then it goes up to a bend while the ice bag is on. It goes

mmmmmmmmmmnnnnnnnnnn,

moving your leg up s-l-o-w-l-y and then back down. That’s the first two weeks. Did that hurt? Oh, fuck, yeah!

I was on painkillers, but still . . . it’s what you have to do to get out—the only way out is through. It took four months, but after that I was in pretty good shape. It still hurt, but my knee was well enough for me to go on the next Aerosmith tour. We had to go right out, because by that time “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” was number one, and all these opportunities came up. We played Madison Square Garden again.

I brought a girl out on tour with me, she massaged me three times a day: iced it, massaged it, iced it. When they massage a scar, it goes away. That’s why I don’t have any scars. I wore a leg brace onstage for six months after that. When I first got it, it was mummy white. I said, “Paint it black!” I cut all my pants off at the knee and it looked pretty cool. Steven, the bionic man. We had to tour, so that was that.

I

n December 1998, I went to the White House with the band, and fuck me if President Clinton wasn’t being impeached

that day

. The Senate broke, they called him up, and said, “Mr. President, you’re going to be impeached; we’re on our way over.” So all the trucks were there from the news media (as you can only imagine). We were all at the Secret Service shop in the basement. There’s a firing range down there and a major tunnel with a train that’s propelled through a pneumatic tube. You strap yourself in and it goes

ptchoooo-oooo!

to some DUM (Deep Underground Military) facility. America’s full of DUMs. But enough about our managers.

We’re getting walked around, given little gifts—Secret Service golf balls! Clinton’s press secretary comes down and goes, “Steven, do me a favor, can you come upstairs, please?” I said, “That’s fine with me, but we’re playing tonight.” “What time do you need to be there?” “Six, and the gig is three hours away.” “No problem, we’ll get you there.” They took us upstairs to a waiting room to hang out till Bill Clinton could come meet us. And where do you think they put us? The Situation Room—I’m sitting in the president’s chair looking around at all the monitors. We met with Bill (briefly—he was kinda busy that day, ya think?). Then we were escorted quietly out of the White House. We were walked out to a police escort—off to Quantico, FBI headquarters to stroll down a street with full-on machine guns. They let me shoot dummies at a practice range there that’s mocked up to look like a city block. Animatronic figures pop out at you as you walk around. The head of a terrorist leans out and you shoot at it, then an animatronic little girl leans out with her doll—ooops!

“I

Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” was nominated for an Oscar for best original song—it was the theme song for

Armageddon

—which was especially sweet since Liv was one of the stars of the movie. I was going to perform it at the Academy Awards. I peeked through the curtain and looked down and there’s Eric Clapton and Sting and Madonna and all the people from my era, sitting in the front row. Just before the curtain opened my keyboard player kicked a cord out and it took out my ears so I couldn’t hear the mix. When the performance starts I’m supposed to be up front with the guy playing the cello for the opening line of the song. They went “Sixty seconds!” “But, wait,” I said, “I can’t hear anything! Is that mic on?” I walked back to my production man and told him, “Don’t let them open the fucking curtain yet, I have no ears. Do not open—” They did it anyway. And so the song started and I was twenty feet from the cello player. I wasn’t about to

run

up to the front of the stage; everyone in the place would have laughed, “

A-HA-HA-HA!

Look at Steven, he lost his mark!” I’m a little more professional than that. I walked up

real slowly

. But by the time I got to the cello player—probably thirty feet away—the first verse was gone. I blew the first verse. Live TV at the Oscars! Oh, man.

W

e’d got our number one hit record, been at the Grammys, and still had a half-a-Grammy left, sung at the Academy Awards. So I had to go through a few rough periods—but it was all worth it. Aerosmith was at full tilt. I was happily married to Teresa with two beautiful children, Chelsea and Taj, plus my Liv and Mia. Life was good and I had nothing to worry about. Or so I thought. . . .

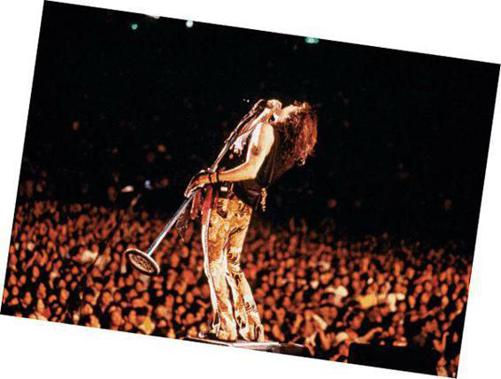

M

illenium Show at the Osaka Dome, Japan. The end of the world? My ass! (William Hames for Aerosmith)

Holy Smoke,

Quest for the

Grand Pashmina,

and the Big Chill

of Twenty Summers

I

found myself making snorting sounds:

fffueh-ffuh-fffeuh-fuh-feu-feu

. Snuffling like an armadillo in search of fire ants. My nasal passages were completely clogged. No, not from the coke! Fuck, no. I stopped in 1980. I stopped smoking. I stopped everything, well, for X number of years anyway. To this day, no damage to the nasal passages. No, the snuffling was from the way I slept (I used to sleep on my back) and the fog juice. My sinuses had mutated, become an alien life form. Thirty years of breathing in the damn oil-based fog juice, that’s the stage smoke they use to enhance the beams of light. The smoke makes everything look bigger and more dramatic. It’s HOLY SMOKE! You see more colors.

This is how it works: the guy doing the lights hits a foot switch that activates the smoke machine behind the drum riser and up comes this apocalyptic fog juice. It’s blowing out onstage and I’m inhaling it, taking a deep breath to launch into the song:

“I could lie awake

”

. . .

you know . . . “

just to heh-heheh-heh-hear you bruh-breathing!

” and I’m going,

ah-heh-ah-hehh-ahh.

It’s like being a fucking monkey in a lab experiment. A demented researcher is saying, “All right, let’s fill this room full of smoke, get the little chimp to sing at the top of his lungs for twenty years, and then we’ll run some tests.”

If I get sick I’ve got to cancel. And when Aerosmith cancels a show it’s a

million dollars

! I tell you, the worst time in my life is when I’m taking a shower or sitting in my room, it’s one o’clock in the afternoon and we’ve got a gig that night, and I go, “

Fuck!

I can’t do it.” My voice is gone from laryngitis. Either I have a high raspy whine or a deep, bullfroggy honk, but either way I can’t sing. I

hate

that, I lose it, knowing that there’s twenty thousand people on their way to the concert. They’re high and happy, thinking they’re going to get laid tonight, and now they’re going to find out over the radio that the concert is off and they’re all going to go,

Awwwww

shit! I

feel

for them. Now someone like Axl Rose, on the other hand, will handcuff himself to the toilet at the hotel and have people wait four

hours

for him to show. Why does he do it? That’s just how Axl is. He’ll say, “The marbles were thrown and the color red didn’t show up, so I can’t get there tonight.” Some astrologi-theosophical omen like that and he won’t move.

We have to take out eight million dollars in insurance in case anything goes wrong with Steven the singing monkey. Anything could happen to anyone else in the band—unless they break a leg—and the show would go on. So once again Steven’s the designated patient. Rather than the band spending insurance money if I get sick, I take a shot of a type of cortisone to reduce the sinus inflammation—it’s called the Medrol Dose Pack, and it shrinks them.

After years of inhaling fog juice I had a serious case of sinusitis. Gunk dripped down my throat like a slow-running faucet. They had to operate. Roto-Rootered my sinuses, stuffed them with cotton. I’m lying in bed that night after the operation and I wake up ’cause I’m going

glllk-glkkk-gulpgm-glllk

. Like I’m swallowing in my sleep, going, “What is that warm mucuslike gunk?” I reach over and turn the light on and—oh, my god!—blood is pouring out of my nose! Dripping like that thin stream of water out of the faucet when you’re trying to fill the little hole in your water gun. Except it wasn’t a faucet, it was my nose. And it wasn’t water . . . it was blood.

I freaked out. I said to my wife, “Teresa! Quick!” She went in the other room and got a wad of toilet paper. After a minute it was soaked. More toilet paper: soaked. With blood. When a human sees that much blood, it’s “Call an ambulance!” Ambulance came, took me to the hospital. I’m lying there; nobody’s doing anything. “You guys! I’m bleeding to death here!” That hospital didn’t have the capabilities to do anything about my bleeding, so they stuffed me up with cotton and rushed me down to Mass General. They cauterized my nose at one o’clock in the morning, and the bleeding stopped. Two hours of hell! Blood all over the place! I had an operation, then everything was fine. My nose is still fine, thank you. No schmutz in my lungs, either:

hhuh-hhuh-hhuh-hhuh-hhuh

. Did you hear anything?

W

hen I first blew a tire, so to speak, in my throat, people started saying, “Steven Tyler has cancer!” What I actually had was a broken blood vessel in my throat. When I had throat surgery the doctor said, “No talking for three weeks.” Now how was I supposed to do that? I went back to see him and he said, “You talked!” I got deep with it, I said, “What are you talking about, Doc? There isn’t a soul on this planet who can shut up for a day, never mind three weeks. Unless I tape my mouth up, there’s no way. We’re humans, we’re primates—we talk—and talking is my life. People talk in their sleep, they talk to themselves, and personally I suffer from being vaccinated with a phonograph needle!” “Steven, another week!” he told me and he did that three times. It went on for five weeks—it was a fucking nightmare.

The way they treat a broken blood vessel in the throat is just astounding. They put a tiny camera down my throat with a laser attached to it. On a computer they draw a line around the spot with the green laser beam and then they delete it the way you would a sentence in a word-processing program. They tap on the spot and it gets rid of it. Dr. Zeitels is in there with a green laser and he’s going, “Gone, gone, gone, gone—” The green laser eats the blood under the skin, evaporates it, it’s gone!

Star Trek

. I watched it back on a monitor, it was un-fucking-believable.

While Dr. Zeitels was working on my throat I told him, “I have an idea. We’re playing in Minneapolis. Why don’t you fly to the gig with me, bring your gear, that way you can film me before a show, during Joe’s solo, and after the show. You’ll get to see what it’s like to be me.” Flew him out, he did it. All the way, I’m going, “Doc, I mean, what if we went public with this?” “Well, you see, no one’s really done this operation on film before.” “So, let’s do it. I’m a lead singer—what more dramatic candidate for this operation could you get?” We thought about it for six or seven years and then we simply took the film footage of him zapping the blood vessels with a laser, some performance stuff, and they began to put the sequence together.

I thought they should get me singing “Dream On.” As he was going down my throat, I said, “Oh, shit! If you’re going to film me singing ‘Dream On’ while I’m in the chair, I wanna caterwaul the chorus, ‘Dream o-on!’ I couldn’t do that if he went down my throat, so he went down my nose instead. He put the microcamera in and I really slammed it out, ‘

DRE-am o-ONNNN . . . YEee-AH!

’ ”

The footage ended up on

National Geographic

’s

The Human Body

. When they did the show you heard me singing in the chair, the doctor talking, and all that stuff, and when I sang that, they could cut to me onstage singing it for real.

While I was at MIT Dr. Zeitels give me a tour of the lab. They put me in a red jumpsuit and took me down to the lab to see rats growing human ears. What they’re doing there is pure science fiction. They paint organic webbing with human skin on it and attach it to the rat, so now it’s getting a blood supply, it’s absorbing it—it’s called osmosis.

T

he whole

National Geographic

special was interesting because it was about the physics of singing, how your throat functions as a musical instrument, and how that instrument can bend, melt, twist, and wring emotions out of words. Sung words are mutations of written words. You come to a phrase in a song, your brain gets altered—words behave very strangely when they’re fused with music. What

is

music anyway? And how does it go from

bom-da-bom-bom

into a song? When we sing we convey emotion by raising the pitch; the notes change the form of the words. Tone determines emotion: praise, stop, pay attention, comfort. A melody with a rising tone keeps a child calm; a minor second is jarring. Music literally touches you. Sound is touch at a distance; it touches your brain.

Monotone speech is robotic. In tone languages, words take on meanings from different pitches. In English we don’t depend on tone for meaning, but in Mandarin Chinese, for instance, tone determines the meaning. Depending on the tone you use,

ma

can mean “mother,” “hemp,” “horse,” or “reproach.” The Chinese are very adept at using different pitches to indicate meaning, but

perfect

pitch is very rare: like having a tuning fork in your brain. Everything has a voice and a key: a car horn is an F, bells are between D flat and B. One person in ten thousand has perfect pitch. Mozart, Bach, and Beethoven all had perfect pitch.

I’ve spent my life listening to singers and realizing which ones could sing really well and are

still

lousy. It has nothing to do with perfect pitch or music lessons. Thousands of people sing great, with well-trained voices. The ones that have character in their voices are rare. Fucked-up voices with a ton of character—that’s my idea of a great voice. My first album, people were going, “Steven, I know that’s you singing, but how come it doesn’t sound like you?” “Well,” I tell them, “I didn’t like my angelic voice so I did it in my fake ghetto voice.” It was then I realized that I needed to fuck it up

good

. Like the great ones, like Janis:

“Whoa Lor-ord woncha buy me-eh a Merrrcedees Benz!”

That rusty, ornery, bar-at-closing-time voice. She could fuck up a song brilliantly. She had a raspy, croaky voice, she was

born

with a raspy voice. She had vocal chops that no other singer had. She wasn’t the perfect American girl. She was skinny, had long fucking thick-ass hair, R. Crumb running out of the pages. You know Angel Food McSpade? She was her fucking white counterpart.

That was Janis! And don’t I know that! I’ve been around people who break into a tremulous vibrato:

“Ha-a-a-a-a-a-a-a to-o-o-o-o dre-e-e-e-am the-e-e-e impossible dre-e-e-e-e-m.”

They’ve

learned

that shit. They’ve spent thousands of dollars to be able to do that fucking vibrato that doesn’t belong in

any

fucking song. There’s a few who know how to bend it. Robert Plant would do a little bendy thing at the end of a song, but it was all from feeling. You go to Broadway and a guy looks up at the lights and goes,

“Hmmmm-hmmm-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-M-M-M-M-M-M-M-M-M-M-NNNN-NNN-NNN-NNNNNNNN!”

His fucking head goes bobbing back. It’s all a learned, conditioned thing; it’s dead as a doornail and stale as a stranded whale.

What about:

I got a reefer headed woman

She fell right down from the sky

Lord, I gots to drink me two fifths of whisky

Just to get half as high?

How epiphanous is that to a camp song? You know

Froggie went a walking one fine day a-woo, a-woo

Froggie went a walking one fine day

Met Miss Mousie on the way a-woo, a-woo

Ridin’ into town alone

By the light of the moon

. . . “a-woo” is the same fucking, happy, in-your-face yelp as the chorus to “She Loves You.”

With Aerosmith we do so many different flavors: “Game On,” “Shank After Rollin’,” “Seasons of Wither,” “Nine Lives,” “Taste of India,” “Ain’t That a Bitch.” We do down-home Delta blues, sleaze boogie, anthems, mandolins, steel-drum calypso, wailing sirens, cat-in-heat yelps, sentimental ballads, metal, Beatles covers, mooing killer whales, and the Shangri Las. You can’t put your finger on what we do, because we do a lot of different kinds of music, unlike Metallica, which does only one genre. Have you ever heard a slow Metallica song? Is there one that you could dance to at a prom? If you asked them, they’d go, “Why would we?”

You can know all the technical stuff of singing, but it doesn’t matter in the end because it’s too over the heads of the audience anyway. Once you learn the nuances of music, you’ve got to take it somewhere else. There comes a point in most great musicians’ evolution where they no longer hear all that underpinning. They only know the words that are thrown over the music:

“Every time that I look in the mirror . . .”

You take off from that. You don’t know what you’re singing or what chord it is.