Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (2 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

H

appy days—Mom and me and Crickett, my Toy Fox Terrier, 1954. (Ernie Tallarico)

“You gotta learn how to read ’em yourself,” she said. Up until then I’d been reading along with her as she pointed to the words. We did this for months until she knew I kinda had the idea, then suddenly there’s no Mom looking over my shoulder. She just left the book by my bed and I became distraught. “Mom, I wanna

hear

the stories. Why won’t you read to me anymore?!” I said. And then one night I thought to myself, “Uh-oh, now I gotta get smart.” Naah. . . . I’ll just become a musician and write my own stories and myths . . . Aeromyths.

Mom used to tell me of a man she’d seen on the

Steve Allen Show,

in 1956 when I was eight. His name was Gypsy Boots. He was the original hippie, a guy who lived in a tree with hair down to his waist and who promoted health food and yoga. Gypsy was

the

protohippie. In the early thirties he had dropped out of high school, wandered to California with a bunch of other so-called vagabonds, lived off the land, slept in caves and trees, and bathed in waterfalls. I was totally seduced by that lifestyle. Boots’s message was this: As primitive as his world seemed, he wanted people to think that he would live forever. Hey, he almost did, dying just eleven days before his ninetieth birthday in 1994.

Next in my life came a bohemian composer named Eden Ahbez, who wrote a song called “Nature Boy” (which my mom heard on a Nat King Cole record). He camped out below the first L in the Hollywood sign, studied Oriental mysticism, and, like Gypsy Boots, he lived on vegetables, fruits, and nuts. My mom sang that song to me before I went to sleep. I’ll never forget how it made me think that I was her nature boy.

The song tells the story of how one day an enchanted wandering Nature Boy—wise and shy, with a sad, glittering eye—crosses the path of the singer. They sit by the fire and talk of philosophers and knaves and cabbages and kings. As the boy gets up to leave he imparts the secret of life: To love and be loved is all we know and all we need to know. With that Nature Boy vanishes into the night as mysteriously as he had come.

Unfortunately the people who own the rights to “Nature Boy” won’t let me publish the actual words to the song in this book (still, you can just Google them), but I promise it will be on my solo album come hell or high water.

Then there was Moondog. What a fantastic character, a blind musician who dressed up like a Viking with a helmet and horns and a spear to match. He hung out on the corner of Fifty-sixth Street and Sixth Avenue. I saw and smelled him every morning on my way to school. Oddly enough, he lived up in the Bronx, apparently in the woods, back behind the apartment buildings I grew up in. Was that a coincidence or was that God secretly telling me, “Steven, thou shalt become the Moondog of your generation”? Or at least the leader of a rock ’n’ roll band.

What I heard about Moondog was that

he

wrote “Nature Boy,” but what do I know? Maybe Eden Ahbez is Moondog spelled backward. . . .

My mother’s birth name was Susan Rey Blancha. At sixteen she joined the WACs (Women’s Army Corps). She met my dad while they were both at Fort Dix in New Jersey during World War II. One night he had a date with a woman who was rooming with my mom. The roommate stood him up, and instead he was greeted by my mother, who happened to be playing the piano at the time. My dad walked over to her and said, “You’re playin’ it wrong.” It was love at first fight! They got married and had lil ol’ Lynda, my sister, and lil ol’ me came two years later. Ha-ha! That’s my mom, that’s my dad, and that’s why I’m so fuckin’ detail-oriented—and such a maniac. I got the traits that I don’t want and the ones I do. Because you’re an offspring, you pick up those traits unconsciously, in case you haven’t noticed. You become your mom!

M

y mother, Susan Rey Blancha, at eighteen in 1932. (Ernie Tallarico)

So that’s how I happened, 1948, a rare mixture of classical Juilliard boy meets country pinup girl, who, by the way, looked like a cross between Jean Harlow and Marlene Dietrich with a tinge of Elly May Clampett. And if God’s in the details—and we know She is—then I’m the perfect combination. I’m the N in my parents’ DNA. So now, if anyone’s mad at me and calls me a dick, I know they really mean Fort Dix. My daughter Chelsea always thought God was a woman from the day she was born. It was so nurturing hearing that from a child, that God would have to be a woman, that I just never questioned it. (No wonder I keep watching

Oprah

.)

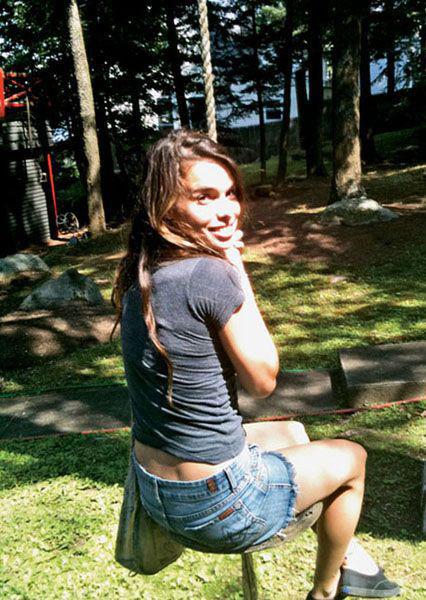

C

helsea Anna Tyler Tallarico on our rope swing, Sunapee, New Hampshire, 2008. (Steven Tallarico)

Mom was a free spirit, a hippie before her time. She loved folktales and fairy tales but hated

Star Trek

. She used to say, “Why are you watching that? All the stories are from the Bible . . . just six ways from Sunday. Get the Bible!” And I thought, “Oh, boy, that’s just what I wanna do after I’ve rolled a doobie and I’m smokin’ it with Spock.” And by the way, that’s why teenagers today go, “Whatever!” But you know—and I can only admit this in the cocktail hours of my life—

SHE WAS RIGHT

!!!!! Isaac Asimov’s

I Robot,

Aldous Huxley’s

Brave New World,

that’s where they got their inspiration. In the same way that Elvis got his sound from Sister Rosetta Tharpe (I dare you to YouTube her

right now

), Ernest Tubb, Bob Wills, and Roy Orbison. And they, in turn, begat the Beatles and they begat the Stones and they begat Elton John, Marvin Gaye, Carole King, and . . . Aerosmith. So study your rock history, son. That be the Bible of the Blues.

I

was three when we moved to the Bronx, to an apartment building at 5610 Netherland Avenue, around the corner from where the comic book characters Archie and Veronica supposedly lived (I guess that makes me Jughead). We lived there till I was nine—on the top floor, and the view was spectacular. I would sneak out the window onto the fire escape on hot summer nights and pretend I was Spider-Man. The living room was a magical space. It was literally eight feet by twelve! There was a TV in the corner that was dwarfed by Dad’s Steinway grand piano. There’s my dad sitting at the piano, practicing three hours every day, and me building my imaginary world under his piano.

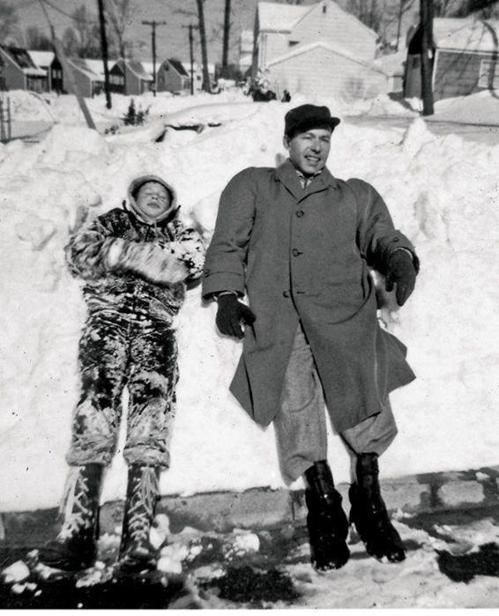

M

e and Dad, 1958. It

did

snow more back then. (Ernie Tallarico)

It was a musical labyrinth where even a three-year-old child could be whisked away into the land of psychoacoustics, where beings such as myself could get lost dancing between the notes. I

lived

under that piano, and to this day I still love getting lost under the cosmic hood of all things. Getting

into

it. Beyond examining the nanos, I want to know about what lives in the fifth within a triad . . . as opposed to

DRINKING

a fifth! I’ve certainly got the psycho part . . . now if I could only get the acoustic part down (although I did write a little ditty called “Season of Wither”).

And that’s where I grew up, under the piano, listening and living in between the notes of Chopin, Bach, Beethoven, Debussy. That’s where I got that “Dream On” chordage. Dad went to Juilliard and ended up playing at Carnegie Hall; when I asked him, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” he said, like an Italian Groucho, “Practice, my son, practice.” The piano was his mistress. Every

key

on that piano had its own personal and emotional resonance for him. He didn’t play by rote. God, every note was like a first kiss, and he read music like it was written for him.

I remember crawling up underneath the piano and running my fingers on top of the soundboards and feeling around. It was a little dusty, and as I was looking up, dust spilled down and hit me in the eyes—dust from a hundred years ago . . . ancient piano dust. It fell in my eyes and I thought, “Wow! Beethoven dust—the very stuff he breathed.”

It was a full-blown Steinway grand piano, not a little upright in the corner—a big shiny black whale with black and white teeth that swims at the bottom of my mind and from a great depth hums strange tunes that come from I know not where.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

had nothing on me.

Later on, I went back to visit 5610 Netherland Avenue. I knocked on the door of apartment 6G, my old apartment. It had been years, and the man who answered was drunk and in his underwear and undershirt.

“Dad?” I asked. He cocked his head like Nipper, the RCA dog.

“Hi, I’m—” I started to say.

“Oh, I know who

you

are,” said he. “From the TV. . . . What are you doin’ here?”

“I used to live here,” I said.

“Well raise my rent!” said he.

So I went in and looked around, and doesn’t it always seem that the apartments we all grew up in are so much smaller compared to how they felt thirty years ago? My god, the kitchen was tiny, four by six! The bedroom I grew up in with my sister, Lynda, and my parents’ master bedroom facing the courtyard—you couldn’t have changed your

mind

in there, never mind your clothes. How the hell did my father

get

a Steinway grand into that living room? So weird seeing this very tiny apartment with an even smaller black-and-white-screen TV on which I’d watched in wide-eyed abandon shows like

The Mickey Mouse Club

and

The Wonderful World of Disney,

which premiered on October 27, 1954. So between growing up at three underneath a piano and seeing my black-and-white television world turn into color by the age of six, that was enough right there to prepare me for life. I couldn’t wait to jump into the middle of it.