Divine Fury (32 page)

Authors: Darrin M. McMahon

FIGURE 4.7.

Evil genius. The German caption to this anonymous caricature of Napoleon is a dark play on Martin Luther’s translation of Matthew 17:5: “This is my beloved son, with whom I am well pleased.”

Napoleonmuseum, Thurgau, Switzerland

.

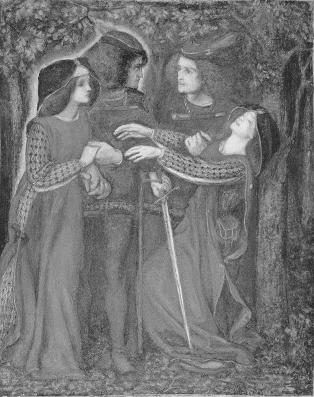

FIGURE 4.8.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

How They Met Themselves

, 1851–1860. The theme of the doppelgänger, which fascinated Rossetti and many others of the age, was a nineteenth-century iteration of the venerable notion of the spiritual double.

Copyright © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 4.9.

Josef Danhauser,

Franz Liszt at the Piano

, 1840. Genius worshipping genius. Liszt, Alexandre Dumas, George Sand, and the Countess Marie d’Agoult (all seated) are joined by Hector Berlioz, Niccolò Paganini, and Gioachino Rossini (all standing) in reverent homage before the bust of Beethoven. A painting of Byron on the wall completes the image of what Germans would later describe as the “brotherhood of genius” (notwithstanding the two women depicted here), the universal fellowship of the saints.

Bpk, Berlin / Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany / Jürgen Liepe / Art Resource, New York

.

Schopenhauer developed that same contention at length in an influential account, describing “suffering” as the “essential martyrdom of genius.” Geniuses were often regarded as “useless” and “unprofitable” in the eyes of the world, he claimed, and they were subject themselves to “violent emotions and irrational passions” that rendered them unfit for normal human dealings.” Geniuses felt too much, they saw too much, and they saw what others did not. As Schopenhauer added later in developing the point, “the genius perceives a world different from [ordinary men], though only by looking more deeply into the world that lies before them also.” It was that very capacity of penetration and insight that allowed the genius to expose hidden truths in his creation, and in so revealing, to redeem. The genius suffered, like all martyrs, so that others could be healed. He sacrificed himself so that those, now blind, could see. Through the soothing balm of his creation, men and women could suspend the restless cravings of the will-to-life that moves through us all and know a measure of transcendence and peace.

38

The martyrdom of genius necessarily entailed rejection. Even Christ had been denied and had perished on the cross, believing himself forsaken by his Father. In the genius’s alienation and the alleged miscomprehension of his contemporaries lay the basis for a powerful trope—the Romantic trope of the misunderstood genius, unappreciated or undervalued in his—or her—own lifetime. This trope, in fact, lent itself particularly well to the case of women, who could complain with justice that their merits were undervalued, where not entirely ignored. The heroine of Madame de Staël’s novel

Corinne

(1807), a genius who bears a distinct resemblance to Staël herself, dramatizes the plight of the brilliant woman in an uncomprehending world. It was, regardless of sex, a general Romantic theme. As Isaac Disraeli, the father of future British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli and author of an important book on the character of men of genius, declared, “the occupations, the amusements, and the ardour of the man of genius are at discord with

the artificial habits of life,” with the result that “the genius in society is often in a state of suffering.” Such suffering was painful in itself, but it could also have the effect of precluding geniuses from fully realizing their gifts. The Scottish poet Robert Burns was one such figure, at least in the reckoning of Thomas Carlyle, whose own influential

On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History

played a crucial role in popularizing the Romantic cult of genius in the nineteenth century. Despite being “a giant Original Man” and “the most gifted British soul” of his age, Burns’s tragically short life was lived largely in penury and oblivion. And in his final years, when he received a modicum of the recognition he deserved, things were no better. Disturbing Burns’s tranquility and disrupting his work, “Lion-hunters” stalked the literary lion. They were, Carlyle alleged, “the ruin and the death” of him.

39

Carlyle’s complaint that Burns was first underappreciated and then appreciated too much speaks to the dilemma of the modern celebrity, who is forever in the public eye, but never really seen. Rousseau, a Romantic hero, had nursed a similar complaint, and in the nineteenth century both Byron and Beethoven did, too. On one level, theirs was a perfectly natural response to the unprecedented pressures of acclaim—pressures that those who were deemed geniuses within their lifetimes, such as Byron and Beethoven, experienced with a particular intensity. For the very definition of the original genius was that the genius was original—unique, singular, one of a kind. It was a priceless quality in an economy of fame, as Beethoven cheekily explained to his patron, Prince Lichnowsky, in asserting the rights of the new aristocracy of genius: “Prince! What you are, you are by circumstance and birth. What I am, I am through myself. Of princes there have been and will be thousands. Of Beethovens there is only one.” But although such singularity was precious, it could make for dramatic isolation, a position highlighted in Romantic painting, where the “lonely genius” is often set apart, portrayed as solitary and distinct. And it could also make for prying eyes, which peered into the private lives of geniuses as they were exposed in a flourishing literary press. The revelation of Byron’s originality—which included sleeping with his half-sister and a gaggle of other people’s wives—got him hounded out of London; scandal and celebrity followed him across Europe in a way that slowly took its toll. As Byron himself observed, after invoking the Pseudo-Aristotelian association of melancholy with men of eminence: “Whether I am a Genius or not, I have been called such by my friends as well as enemies, and in more countries and languages than one, and also within a not very long period of

existence. Of my Genius, I can say nothing, but of my melancholy that it is ‘increasing and ought to be diminished.’ But how?”

40

Byron was aware that his own melancholy was a product, in part, of his celebrity. But that awareness did not prevent him from universalizing his particular condition. Geniuses were inherently prone to madness and despair, he said, and poets, especially, were a “marked race,” destined for disappointment, misunderstanding, and neglect, regardless of whether they were discovered or not. The simultaneous complaint that geniuses were both underappreciated and appreciated too much was, in part, an authentic response to the dilemma of nascent celebrity. But it was also a paradox and a pose, an unresolved contradiction. Was the genius a martyr, or the master of humanity? An individual alienated from the many, or the apple of their eyes? A legislator of the world, or a hero unacknowledged and brought to despair? The Romantics could never really say for sure, because they wanted it both ways.

Which is only fitting: genius, like the “self” of the poet Walt Whitman, contained multitudes—contrasting and at times conflicting voices. As Carlyle affirmed, that worked to the genius’s advantage. “It is the first property of genius to grow in spite of contradiction,” he noted. “The vital germ pushes itself through the dull soil.” Romantic genius nourished itself in this way, working through contradictions both external and internal. Externally, a variety of impediments—from the pressures of social conformity to public incomprehension and alienation—were ready to divert the shoots of the Romantic self, but internally, dangerous cankers and diseases threatened to attack the stalk at its root. Madness was the most common of these threats, treated as all but inseparable from genius itself. The “constant transition into madness” from the suffering of genius, Schopenhauer explained, was not only apparent from the “biographies of great men” (he cited Rousseau and Byron as examples), but also put on display in institutional settings. “I must mention having found, on frequent visits to lunatic asylums, individual subjects endowed with unmistakable gifts,” he wrote. It was evidence, he believed, of the “direct contact between genius and madness.” More to the point, it was a sign of the times, for pathological genius was becoming an important subject of medical and psychological investigation. And though the language of the laboratory and the asylum did not always register in a Romantic key, it tended nonetheless to reaffirm a common assertion: genius and madness shared a necessary connection. Mental instability was an essential aspect of the martyrdom of genius. If genius was a gift, it was also a curse.

41

In accentuating and bringing to the fore the long-standing association between genius and mental affliction, the Romantics updated its image, giving it a new style and “look.” An intensely brooding Beethoven, wild-eyed with wild hair, replaced the dreamy melancholia of the Renaissance sage, just as the tortured, restless striving of a Byron could stand in for the fury of the

furor poeticus

. Romantics were quick to trace their own associations onto the past (as their use of the image of Tasso nicely conveys), finding persecuted geniuses throughout human history. But at the same time, they partook of history’s bequests, enhancing their own image, if only indirectly, by reference to a venerable association. The ancient link between genius and madness hinted at a connection to the specially chosen one, the poet or prophet or ecstatic seer who channeled the voice of the divine. Madness continued to hint at a form of possession, suggesting that those in thrall to genius were in the grip of a greater power.

42

Yet the contradictions of madness were such that it was never easy to distinguish the devil from the divine. In the ranting of one’s own mind, a ghost might be taken for an angel, a demon for a genius, the voice of Satan for the voice of God. The Romantics faced that possibility head on. Gazing fixedly at Delacroix’s painting of Tasso, the French poet Charles Baudelaire glimpsed something of this confusion, seeing a “genius, imprisoned in an unhealthy hovel,” haunted by “swarms of ghosts,” intoxicating laughter, doubts and fear, and strange cries that reverberated from the walls of his dungeon. Well acquainted with hallucinations and the seductions of evil, Baudelaire interpreted the painting as a struggle of the soul, the imagination’s battle with reality. The great Italian Romantic poet Giacomo Leopardi also detected genius—and a

genius

—in Tasso’s plight. In his

Dialogo di Torquato Tasso e del suo genio familiare

, Leopardi presents a dialogue between the imprisoned bard and his tutelary spirit (

suo genio familiare

) as a metaphor for a man who is tormented by delusions. It is a Romantic rendering of the temptations of the saint in his cell. Tasso conceives initially of his

genius

as a source of comfort. “My mind has grown accustomed to talking to itself,” he confesses during the course of a long conversation. “I almost feel as though there were people in my head arguing with one another.” But when Tasso inquires where the

genius

normally resides so that he may summon him again, the spirit reveals that he is a figment of his mind. “You have not found out yet?” “In qualche liquore generoso,” comes the answer: “In some robust drink.” A spirit who dwells in strong spirits—or a vile of opium—this is a genie in a bottle of a different kind, a dark

genius

who preys on genius in place of granting a wish, disturbing the creative mind.

43

Leopardi’s conjuring, like Baudelaire’s poetic sighting of ghosts, was by no means an isolated occurrence. With their penchant for the Gothic and ghoulish, Romantic artists frequently summoned spirits, and their indulgence in mind-altering drugs, such as opium and hashish, meant that they occasionally saw them. Many also evinced a strong interest in esoterism and the occult. But even when they summoned spirits only as a literary device, they gestured at something putatively real, a world of forces that lurked about us and in us, too, forces sinister, frightening, and portentous, beckoning and tempting with not just madness, but perversion, death, and crime. Close to genius hovered evil genius, his ominous brother and twin.