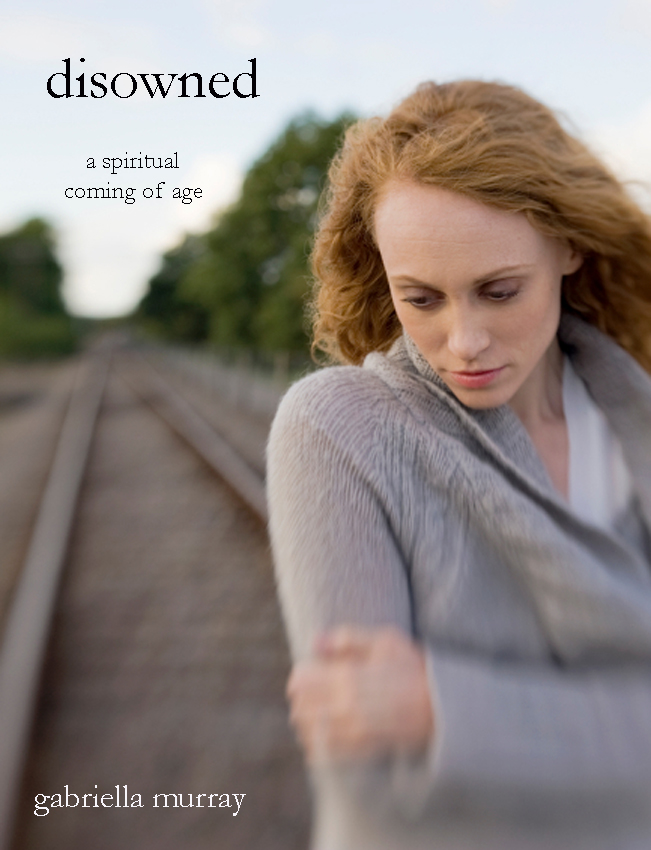

DISOWNED

Authors: Gabriella Murray

disowned

(a spiritual coming of age story)

Gabriella Murray

Also by Gabriella Murray

CONFINEMENT

LOCKED AWAY

Copyright © 2011 by Gabriella Murray

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior permission of the author.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return it and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictionally. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Rivkah Snitofsky, daughter of Malke, granddaughter of Reb Moshe Yitzrok, sits on the stoop in Borough Park Brooklyn, with the commandments of God wrapped around her, and shivers in the cool, evening air.

It is twilight, October 1945, two days past the high holidays with the prayers still lingering in the overcast skies. The war in Europe has just ended and Rivkah will be 13 years old in December, on the first light of Chanukah.

All day long people have been talking. They have been counting on their fingers the number dead and the number living. From inside different houses on the block you can hear sobbing in some, singing in others.

As the afternoon comes to an end, Rivkah paces up and down the hard pavement, listening to everything. God left me here living, she thinks to herself. There must be a reason why?

But some questions have no answers, and here in Borough Park it is forbidden to ask them. Here it is a sin to waste time with foolish thinking, when there is so much important work to be done.

Rivkah stops pacing for a moment and picks up a stray branch on the street. Then she leans down under a tree and writes a list of names in the earth of those who have disappeared. I am writing your names out, she whispers to them, so no one will forget you. Not even me.

There was Faegelle, her mother's second cousin. And Joseph, Berish's son. Joseph was only sixteen years old. They took him quickly, early in the morning, just before the new daylight had a chance to break through.

Rivkah writes each name slowly as the afternoon sun sets over her shoulder, gently lighting the Hebrew letters.Evening comes slowly in Borough Park, not like anywhere else in the world. As the afternoon comes to an end, one by one the doors on the block open and men dressed in black come scurrying out, and flying in all directions, to be on time at the synagogues for evening prayers.

"We praise God, no matter what," Rivkah's grandmother Devorah tells her over and over. "In good times and bad. There is nothing that happens that is not God's will for us."

Rivkah swallows hard whenever she says that. "Everything is God's will for us, grandma? Even what happened to Joseph?"

"Even that. Even that."

The whole world they live in is about twelve square blocks long. They are narrow streets, with thin trees on them, struggling for air. Everyone who is anyone lives on these streets. They live here with their entire families: mothers, father, sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, and of course, their beloved Rabbis. There is nowhere else in the world they have to go.

Each block has at least one or two synagogues on it. Most are only narrow rooms inside people's homes. In the middle of the rooms are long wooden tables strewn with bibles and prayer books where the men sit for hours, praying, learning and repenting their sins. There is even a synagogue behind Ruthie's grocery store, where the men can smell delicious, fresh sour pickles, just as they are begging God to save the entire world. There is only one way to be a real Jew in Borough Park Brooklyn. And it is easy to slip, too easy to fall. Each does what is expected of him. A woman knows her place, so does a man.

It is Rivkah's place to help her grandmother and not go running down the block to her precious Uncle Reb Bershky, who lives three doors down.

"Without you, Uncle Bershky," Rivkah whispers to herself, "I could not go on.

Uncle Reb Bershky is a very tall, thin man who hardly eats and sits alone all day wrapped in his black, satin coat studying the word of God. Nothing else interests him. He spends all day deep inside the sacred pages that are spread out on the table before him. No matter how many pages, Uncle Reb Bershky has read them all. Not only has he read them, he has drunk in every word. Not only has he drunk them, but the words themselves have drunk him in. If you look closely, you can find no separation between them at all.

Thank God, Rivkah thinks, for Uncle Reb Bershky. If he is here praying with us, it is possible that God will take pity and save the entire world.

As Rivkah finishes writing the names out, her grandmother's deep voice calls at her from inside the house. "Rivkah!"

Rivkah flinches.

"What are you doing? Come in!"

"In a minute."

"In a minute nothing. It's getting late. There is still more work to be done."

Rivkah stands up slowly. She has been helping Devorah in her huge, white tile kitchen all day long, chopping onions, peeling carrots and potatoes for chullente, rolling dough. She has dried pots and dishes and stacked cups on the counter top. Now Rivkah turns reluctantly and scrapes her foot hard on the rough pavement.

"Rivkah, do you hear me?" The strong voice booms out at her relentlessly, full of power and demands. There is no escaping when her grandmother calls. "It's getting dark out."

Then, for a moment Devorah's voice subsides, and a sweet silence rises around Rivkah. She leans back down near the tree where some stray bluebells is growing in the earth helter skelter. Rivkah pulls out a handful of them slowly, and places them, one by one, around the names she wrote down. In the quiet of early evening, a few passing sparrows twitter overhead and as Rivkah lifts her head to watch them, she glances at the second floor of the house where her mother and father have their own apartment.

Upstairs in their second floor apartment Rivkah's mother and father live in their own manner, and will not do what is expected of them, ever. Her father does not wear a yarmulke and her mother praises God only as she sees fit, spending the day writing odd poems. No one in the neighborhood visits them, ever.

Nevertheless, the apartment is beautiful, with a big, open front porch covered by branches from a huge cherry tree from the garden below. The branches sway over the porch giving big cherries every spring. Her father Henry loves this tree, and so does her mother Molly.

The kitchen in back of the apartment looks out over another small garden, where Rivkah's grandfather has planted a little arbor of grapes. Small birds come to the ledge of this kitchen all day long and sometimes they come at evening too. "They come to see me," Molly, her mother, tells Rivkah, "because I try to be kind to everybody, and because they know how lonely I am."

Rivkah looks up now and sees her mother walking back and forth slowly on the outside porch. Molly is slender, fragile and beautiful, with warm chestnut hair that is thick like the mane of a wild horse. She will not cover it completely, the most she will do is to tie it back with a silk scarf.

Most of the day Molly lies in a hammock under the cherry tree and writes her poems. She seldom comes downstairs, and has married Henry, rather than one of the righteous men who live on the block.

The apartment also has an overstuffed club chair that Henry, Rivkah's father, loves to sit in when he comes home from work. It is next to a tall, wooden radio. Right now he's probably sitting in it, thinks Rivkah, tuning in stations from Europe and getting news from around the world.

Rivkah knows that if you're different in Borough Park you do not belong. You do what you have to quietly, in secret, and everyone talks. But whatever Henry does, he doesn't hide it.

"I refuse to be ashamed, Molly," he announces to her every morning as he dresses and splashes cologne in big doses over his face. "God made us for one reason only. To be who we are."

Rivkah watches her mother upstairs for a moment, and then calls out to her.

“Mamma, I'm here, downstairs. Answer me."

Molly doesn't answer. She keeps walking back and forth on the open porch, thinking of other things.

"Rivkah, come inside," her grandmother's deep voice pours out of the downstairs kitchen window. "It's getting late."

But tonight, Rivkah can't go in. Upstairs, her mother seems distraught. She and her father are probably arguing again, talking again about when they will move out of Borough Park. Molly cannot go, refuses to leave her family. Henry cannot stay. It is the dream of his life to move away and be a part of the outside world.

"Henry," Molly calls inside, "bend a little. Yield. You're nothing but trouble, and all the neighbors know it. And they're making it harder for Rivkah, too, now day after day."

"So, who do you love, Molly? Me or the neighbors?" her father's strong voice comes calling back.

Rivkah flinches. Every day she prays this struggle will end, but her father seems to enjoy it. He likes hearing her mother say that she chooses him over the whole world.

"Say it out loud. Be proud of it, Molly. Be your own person Tell me again."

Rivkah hears her mother laugh. "I choose you Henry, but still you have to yield. At least wear a yarmulke until you get to the subway, daddy. Then, if you have to, take it off. They're taunting Rivkah more and more."

"You want me to lie?" Henry calls back.

Rivkah feels her face contort with pain. Her father has strong principles he fights for and he will not give one of them up. "There are a hundred ways to be a Jew, Molly" he yells. "I keep what I want in my heart."

"Your heart's not enough for the neighbors. Bend a little, for Rivkah's sake."

"I'm a good man, Molly. Look for yourself." Rivkah sees him come out on the porch. "And soon, we're moving out of here anyway."

Rivkah takes a stick in her hand, bends down and draws circles on the ground. Where could her parents ever move to?

"We're trapped here for a little longer," Henry calls. "But a little while only!"

But no matter how much Henry pleads, Molly refuses to move out of the house she was raised in.

"Give me one good reason I should move away?" she calls now. "Once you've lived in Borough Park, Henry, every other place is thin air."

"We should move because I do not belong here, Molly."

Rivkah clenches her teeth. She knows all Jews belong together, whether they like it or not. It's written they should all stay together. Rivkah tries to move from the spot she is standing in, but can't go front or back. She stays still and hears her father growling

"Have some pity, Molly, I'm begging."

"I have pity," Molly says.

Rivkah looks upstairs again and suddenly sees her father walk out on the porch. Her mother jumps back.

"Don't hate me, Molly" Henry goes closer to her, hungry, eager for warmth.

"How could I hate you, Henry?" she answers and after a few moments holds out her arms to him. Henry flies into them. He can't stand to be too far away.