Disgraceful Archaeology (4 page)

Read Disgraceful Archaeology Online

Authors: Paul Bahn

12

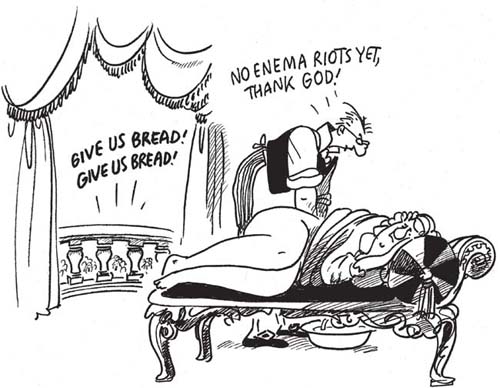

Louis XIV is said to have endured more than 2000 enemas during his reign, often meeting with various dignitaries during the procedure, which clearly made him public enema No. 1 (

13

).

The Late Classic Maya (AD 600–900) may have ritually used hallucinogenic enemas (probably made of mead, tobacco juice, mushrooms and morning glory seeds) to go into a trance state more quickly than through oral consumption. Some are illustrated on their pottery, while certain mysterious artifacts such as slim bone tubes found in graves may also be linked with the practice. Similarly, a prehistoric tomb on the south coast of Peru, dating to 3000–1000 BC, contains a 45-year old man, buried with various artifacts including what is thought to be an

enema apparatus used for hallucinogens or other substances.

13

A rock painting in South Africa’s Free State Province seems to depict the administration of an enema. A figure bends forward with buttocks raised and hands on the ground. A second figure approaches from the right to administer the enema, apparently using a horn fitted with a plunger. The apprehensive patient raises one leg in the air in anticipation of some discomfort. There are two onlookers.

The ancient Egyptians had highly developed medical knowledge — one palace official rejoiced in the title Keeper of the Royal Rectum for his knowledge of enemas (

14

).

The Roman emperor Claudius (ruled AD 41–54) was murdered by being fed poisoned mushrooms — one version is that he fell into a coma but vomited up the entire contents of his stomach and was then poisoned a second time, either by a gruel — the excuse being that he needed food to revive him — or by means of an enema, the excuse being that his bowels must be emptied too.

14

15

Mark Antony, according to Plutarch (the Greek historian of the first century AD), was hated for his drunkenness, his gross intrigues with women, and the many days spent sleeping off his debauches, wandering about with an aching head and befuddled wits, and his many nights spent in revels. The story goes that he once attended a banquet given for the wedding of Hippias the actor; he ate and drank all night, and then, when he was summoned to attend a political meeting early in the morning at the Forum, he appeared in public surfeited with food and vomited into his toga, which one of his friends held ready for him (

15

).

Similarly, the emperor Claudius was always ready for food and drink â it was seldom that he left a dining hall except gorged and sodden; he would then go to bed and sleep supine with his mouth wide open, thus allowing a feather to be put down his throat, which would bring up the superfluous food and drink as vomit.

From ancient Egypt there is a depiction in tomb 49 at Thebes of a woman (presumably hung-over) throwing up, while there is also a Greek vase showing a young harlot comforting a vomiting customer.

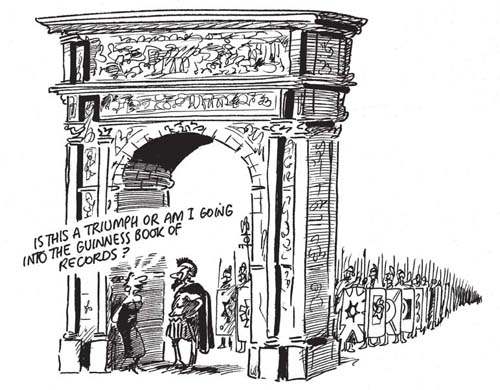

In ancient Rome, some prostitutes did not have the security of a brothel in which to work, but instead practised their trade out of doors under archways — the word ‘fornicate’ is actually derived from the Latin word for ‘arch’ (

fornix

) (

16

).

In Kingston-upon-Hull, in northern England, the medieval council’s attitude to prostitution was ambivalent. The corporation was prepared in the 1490s to let out the town walls and towers and the foreland to the whores, receiving £3-£8 a year in rent.

Among the Greek words for ‘harlot’ a common one is ‘

chamaitype

’, ‘earth-striker’, which shows that they often worked on the ground.

16

The term ‘brothel’ comes from the Old English word for wretch, perhaps referring to the living conditions of the women who worked in the early houses of prostitution. In the medieval period, lower-class women could avoid a life of toil and drudgery by bartering their sexuality, despite the risk of disease; while nuns and married upper-class women could escape the confines of their life by secretly entering a brothel. As long as they profited from the brothels, the nobles and clergy turned a blind eye to the houses devoted to sexual adventure, and indeed were often to be found among the clientele.

At Ashkelon, Israel, the Roman (fourth century) bathhouse contained lamps decorated with erotic images, while a Greek inscription ‘Enter, enjoy and .…’ suggests the bathhouse served as a brothel. It was probably in the red light district — an earlier Roman villa on the site had a room full of lamps decorated with erotic images. As mixed bathing came into vogue in Claudius’s reign, bath houses became like bordellos — in fact one author from Nero’s time wrote of a father who went to the baths, leaving one child at home, only to return from the baths a prospective father of two more. The poet Martial (first century AD) wrote ‘The bathman lets you among the tomb-haunting whores only after putting out his lantern’.

Ancient Egypt, on the other hand, has its ‘Bes chambers’ — early last century archaeologists at Saqqara uncovered four rooms of a mud-brick house; some had brick benches along the walls, and the walls were decorated with representations of the god Bes, 1–1.5 m high, covered with stucco and painted. The dwarf god Bes was often present where physical love is celebrated. In addition, 32 phallic figures were recovered from the debris. So these ‘Bes chambers’ may have been for lady inmates and their clients, or a place of worship linked to procreation.

17

The names of medieval brothel areas were often explicit, and some still survive in contracted form: in fourteenth century London there were Slut’s Hole, Gropecuntlane (now Grape Lane), and Codpiece Alley (now Coppice Alley). Outside the city walls was Cokkeslane. In Paris there was rue Trousse-Puteyne (Whore’s Slit Street) — Mary Stuart is said to have fainted whenever her route took her through there. There was also a rue Grattecon (Scratchcunt street), and rue du Poil au Con (now rue Pélécan), where there were prostitutes who refused to comply with a city regulation requiring them to shave their privates (

17

).

A 2000-year-old brothel has recently been unearthed at Salonika in Greece — all kinds of sex toys were found inside, including a small clay dildo, several erotic figurines, and a red pitcher with a phallic spout. There were also innumerable offerings to Aphrodite, the goddess of love. The room containing this material of the 1st century BC conveniently bordered a bath house.

At Pompeii, sometimes taverns had rooms for prostitution upstairs, where the names of waitresses and prostitutes are found scribbled on walls. The graffiti refer to the women’s vices and attractions, and announce that some women can be had for two ‘

as

’ — the price of a loaf of bread. But these may be written as insults, rather than reflect a true price. The highest price of a woman is given as 16

as

.

Strabo, the Greek geographer of the first century BC, said Corinth had more than 1000 prostitutes; he tells of a Corinthian courtesan who was reproached for being lazy and refusing to do wool working. In her bawdy reply, she punned on the word ‘

histos

’ which can refer to anything erectable, including a loom: ‘Such as I am, in this short time I have taken down three looms [erections] already’.

A fragment by the fourth-century playwright Alexis of Thurii provides a catalogue of tricks whereby an artful madam prepares her novice slave prostitutes for business, including elevator

shoes and false buttocks to satisfy customers who were partial to women’s rear ends. They must also have charming manners: ‘Does she have healthy teeth? By force she’s kept laughing, so that the customers see what a dainty mouth she has. If she doesn’t like to laugh, she must spend the day indoors, with a twig of myrrh upright between her lips, just like the goats’ heads displayed in this way at the butcher shops so that the customers will buy them. That way in time she smiles whether she likes it or not.’

18

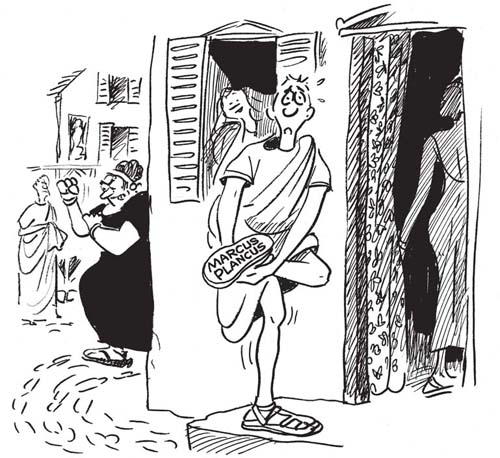

Prostitutes in the ancient port of Ephesus wore sandals with reversed lettering on the sole, so they stamped ‘Follow me’ on the sand as they walked. A carved stone footprint of this kind can be seen in the city ruins (

18

).