Dirty Rice (38 page)

Authors: Gerald Duff

Then I looked around the room full of people talking and laughing and drinking beer and champagne out of bottles and glasses, and I fixed everything I wanted to remember in my mind, moving my eyes from one man to the next of the team I'd played the season with and some of the other folks that hang around a baseball team when it's winning. I saw my locker and the benches and the door to the room that had the showers in it, and I took one more hard look at the door that led out onto the field where the diamond was. I can still call all that up when I need to, each and every thing in its place where it was then, open and ready to the eyes behind my eyes now. Then I walked out onto Hebert Street, full of cars and people milling around, all the ones not wanting to leave yet from the place where a baseball game had just been played.

That feeling that you want to stay as long as you can where a game took place, that you don't want to give up that spot of time yet and get back into the rest of your life where you got to worry about getting something to eat and finding a place you can lie down and sleep in when night comes onâthat way you want to make it last a little longer, the way time is stopped by a baseball game so you can live forever if there's still one man not out yet, all that was like the way I would feel when I'd go to a funeral back in the Nation. When a man or woman dies and you bury them, and the words is said and finished over their grave and the singing and praying is done to mark what's happened, it feels sometimes like if you don't leave the graveyard, the one who can't leave won't be full dead yet. If you could stay forever, the ones you saw covered up with dirt would keep a little life in them as long as you were there with them.

You can't stay, though, because your body is still alive and it wants something to eat and water to drink and a place to lie down for rest, and it craves movement and the light that comes into your eyes when you're in the middle of living. You can put that off for a while, not leaving the truly dead alone in the graveyard, but you can't keep it that way so it will last.

I stepped out of the ballpark in Rayne, Louisiana, onto the street that led away from that place in all the directions open to anywhere in the world a man might choose to go. People hollered my name as I walked past them, calling me Chief Batiste and Gemar and pitcher and Indian and ones I couldn't understand, but not a one of them could call me by my real name, the one I'd learned on my spirit quest into Lost Man Marsh in the Big Thicket when my belly was so empty I was not hungry and Abba Mikko gave me the dream that told me who I really was and what I ought to be called. Nobody in Rayne knew that name, so I didn't have to answer to a soul.

When I walked up Serenity Street where I stayed in Miz Velma Doucette's house, I kept to the side where most of the live oaks stood, the ones with Spanish moss hanging down close enough to touch as you walked under them showing where witches had been, and I did that, trailed my fingers against every clump of gray moss in my reach as I headed for the last building I would enter in Rayne, Louisiana. The moss looked wet, but it was dry to the touch and light in weight, and it had not a thing to do with witches now. Any that had been hiding in that moss was long gone.

Miz Doucette met me at the door, and I gave her my key, and told her I'd leave now, since all the Rice Bird baseball playing was finished and done for good. She wanted to talk about the game she'd heard over the air on the radio, and I let her do that for a while, until she run out of ways to keep speaking about that game now finished and dead.

“I'm about to leave,” I told her, “and I want to thank you for letting me stay in your house and eat the food you cooked. It was real good to me.”

“You liked the spicy dishes, didn't you, Gemar? Lots of the baseball boys that come through here don't. That's why I mention it. It did me good to see you eat.”

“I liked the cooking,” I said. “It was different, and you couldn't tell from looking at what was on the plate how it might taste. It would surprise me every time, and I never got tired of it.”

“Will you come stay in my house again next year, Gemar? I'm going to be all by myself in this big old place, what with Teeny going to be a married woman and living in Lafayette with her husband. It'll be lonesome for me from now on out.”

“If I was to be in Rayne, I wouldn't stay anywhere else but here in your house,” I told her, easing down the hall toward my room to pick up my clothes. “I sure wouldn't.”

“Don't the Rice Birds want you to stay around for a while longer before you leave for home?” Miz Doucette said. “You still got credit for your room and board for almost a month.”

“No, ma'am,” I said. “I don't expect they do. I got to go.”

“I'll give you the rest of the money you ain't going to use up. It comes to over fifteen dollars.”

“You keep that,” I said. “I got some extra I been saving back. What I would like though is one of your sayings on the wall of the room I stayed in. I always look at it a lot.”

“I'm so glad, and you're welcome to it. Which one is it?”

“It's the one that says I need thee every hour. That stuck in my mind, looking at it whenever I was in the room.”

“We do always need Him every hour, don't we? I'm so glad that sentiment speaks to you.”

“It does that,” I said. “And it's always going to, no matter where I end up. I couldn't ever forget it, no matter if I'd try to. I know what I need and what I ain't got.”

After Miz Doucette let me go, I went to my room and put all that was left there that was mine in my tow sack, along with the framed saying, and took one last look around that place. Mike Gonzales' bed when he lived there, the table I wrote my letters home on, and my own bed. I couldn't stand to look at it but for just long enough to be able to say I had done it, that thing I had to do. It burned my eyes like looking into a hot fire real close up. I could feel the water on my eyeballs drying up like sand had been thrown in them. “I need thee every hour,” I said out loud, and then I left the room, the house, Serenity Street, the diamond where the Rice Birds played in Addison Stadium, the town of Rayne, and the state of Louisiana.

Time doesn't have to pass, as far as baseball is concerned, but it does for a man who plays it. Time will get away from you when you're not on the diamond where what the clock says don't count and can't matter. Everywhere else outside the white lines, it does make a difference every tick the clock measures off. I'm now going to end my talking into the microphone and telling about the season of baseball I played in the Evangeline League of Louisiana during the Great Depression in the year they shot their Senator, Huey P. Long, the man they called the Kingfish. They killed him in that big capitol building he'd had built out of white stone when he was governor of the Pelican State.

He was the one that claimed his grandmother was a woman of the Coushatta and that every man is a king.

FICTION

Blue Sabine

Fire Ants and Other Stories

Coasters

Snake Song

Memphis Ribs

That's All Right, Mama: The Unauthorized Life of Elvis's Twin

Graveyard Working

Indian Giver

POETRY

Calling Collect

A Ceremony of Light

NONFICTION

Home Truths: A Deep East Texas Memory

Letters of William Cobbett

William Cobbett and the Politics of Earth

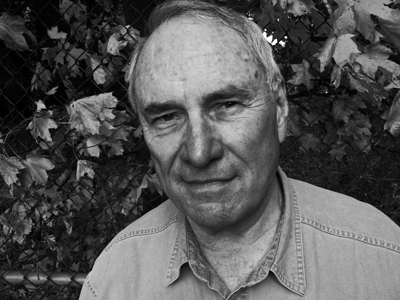

A native of the Texas Gulf Coast, Gerald Duff has taught literature and writing at Vanderbilt University, Kenyon College, Johns Hopkins University, and St. John's College, Oxford. He has served as Academic Dean at Rhodes College, Goucher College, and McKendree University.

He has published thirteen books, including novels, a memoir, and collections of poetry and short stories. His work has appeared in

Kenyon Review

,

Ploughshares

,

Sewanee Review

,

Georgia Review

,

Southwest Review

,

Missouri Review

,

The Nation

, and elsewhere. His writing has won the Cohen Award for Fiction from

Ploughshares

Magazine and the St. Andrews Prize for Poetry, and has been nominated for the PEN/Faulkner Prize and an Edgar Allan Poe Award. His short fiction has been cited in

The Best American Short Stories

,

Pushcart Prizes

, and

The Editors' Choice: Best American Short Fiction

.

His collection of short stories

Fire Ants

was named a finalist by the Texas Institute of Letters for the Jesse Jones Award for the best book of fiction of 2007.

Dirty Rice: A Season in the Evangeline League

is his eighth novel.

For more information visit

www.geraldduff.com

.

It is a fact that the Evangeline Baseball League once existed in Louisiana. All else in this book is fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Front cover image by Laura Smith; used by permission of the artist.

© 2012 by University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press

All rights reserved

University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press

P.O. Box 40831

Lafayette, LA 70504-0831

Distributed by

Garrett County Digital

Digital Design by

Tina Henderson

ISBN: 978-1-891053-88-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Duff, Gerald.

Dirty rice : a season in the Evangeline League / a novel by Gerald Duff.

p. cm. â (Louisiana writers series)

1. Minor league baseballâLouisianaâFiction. 2. Baseball stories. I. Title.

PS3554.U3177D57 2012

813'.54âdc23

2011048806