Dingo Firestorm (2 page)

Getting in contact with people has its challenges, yet one connection often spawns many more. I am most grateful to Dennis Croukamp for putting me in touch with Peter Walls. I spent five riveting hours interviewing General Walls at his home in Plettenberg Bay and a wonderful day in Knysna with him and his wife, Eunice. Over lunch on Thesen Islands, I mentioned to Peter that, try as I may, I had been unable to get in touch with one of the key Dingo personalities, Norman Walsh. Peter opened the door and thus began an invaluable dialogue with this remarkable man and the air force brains behind Operation Dingo. I must also pay a huge tribute to Norman’s wife, Merilyn, for facilitating my dialogue with Norman under very difficult times and for connecting me to Hugh Slatter, a close colleague of Norman’s.

Sadly, both Peter Walls and Norman Walsh passed away shortly after I interviewed them; my great regret is that they never got to read

Dingo Firestorm

. For this reason and out of sheer respect, I have dedicated this book to the memory of these two great men.

I must also thank SAS Commander Brian Robinson, the army brains behind Operation Dingo, for the brief insights he shared with me. Brief, because Brian has no desire to be involved in writing about himself or the SAS, which I understand and respect. I hope I have done justice to his pivotal role in this story.

I started writing this book after interviewing Kevin Milligan, who helped me understand the intricacies of the mass parachute drop. Kevin also shared with me his vivid memories of Operation Dingo, for which I am very thankful. Then I tracked down Vic Wightman, Rich Brand’s deputy at the time of Dingo, who helped me better understand the attack profiles and sight settings for various types of air-to-ground weapons delivery in the Hunter, especially flechette canisters. Thanks also to Vic for sharing his experience of ejecting from an English Electric Lightning supersonic interceptor.

Writing a story some 30 years after the event is always fraught with the ravages that time exerts on people’s memories. In this respect, I have been incredibly fortunate to have documentary evidence of Operation Dingo in the form of the ops orders. I am most thankful to Chris Cocks for allowing me to use the ops orders for the first phase of Operation Dingo, as published in his book

Fireforce

. Chris then put me in touch with Professor Richard Wood, who had spent many hours meticulously copying parts of the original ops orders, air-strike logs, messages, telexes and the debrief summary for the Dingo section of his book

Counter-Strike from the Sky

and for

Operation Dingo

. These invaluable records were held at the British Commonwealth and Empire Museum in Bristol. Richard unselfishly sent me copies of these, for which I am most grateful. These documents underpin the architecture of the story I tell.

Then I had more luck. I remembered that my old skydiving buddy, Keith Samler, formerly a senior Police Special Branch (SB) officer attached to the Selous Scouts, had been a participant in Operation Dingo and had recorded it with a Super 8 camera. I was delighted to learn Keith still had the film, which he generously lent me and then talked me through it. The camera doesn’t lie, and this footage enabled me to see parts of the operation first-hand. Keith also allowed me see ZANLA photographs he and his colleague recovered from the Chimoio base, some of which are reproduced in this book. I cannot adequately describe how valuable this material has been to my account of the story. I am grateful to Keith for the film and photographs and for sharing with me his own (considerable) experiences of Operation Dingo.

When Keith told Ron Reid-Daly, the former commanding officer of the Selous Scouts, that I was writing a story about Dingo, Ron asked to see me. Although he was not directly involved in the operation, Ron was keen to give me his perspective, which has certainly enhanced my understanding of the military landscape leading up to Dingo. I thoroughly enjoyed chatting to ‘Uncle Ron’, sipping red wine on his balcony overlooking False Bay. Sadly, Ron too passed away not long after our meeting.

SAS Captain Robert ‘Bob’ MacKenzie wrote a great account of his experiences of Operation Dingo in the magazine

Soldier of Fortune

. I am most grateful to Colonel Robert Brown, the editor of

Soldier of Fortune

, for granting me permission to use the article, which has effectively allowed me to bring the late Bob MacKenzie back to life.

My thanks also go to Jean Tholet, Ian Smith’s daughter, for giving me permission to quote from his memoirs and to the Flower family for allowing me to use extracts from Ken Flower’s memoirs.

As the project progressed, I found more leads. I was particularly looking for someone who knew Norman Walsh well, because Norman did not enjoy talking about himself. Merilyn Walsh obliged by asking Hugh Slatter, a close friend of Norman’s and pilot of one of the attack aircraft used in Dingo, to contact me. Hugh’s contribution filled a hole in my book. So did the valuable input from Dave Jenkins, who flew as technician/gunner with Norman Walsh and Brian Robinson in the command helicopter. Dave’s perspectives of the battle from the command ship were most helpful.

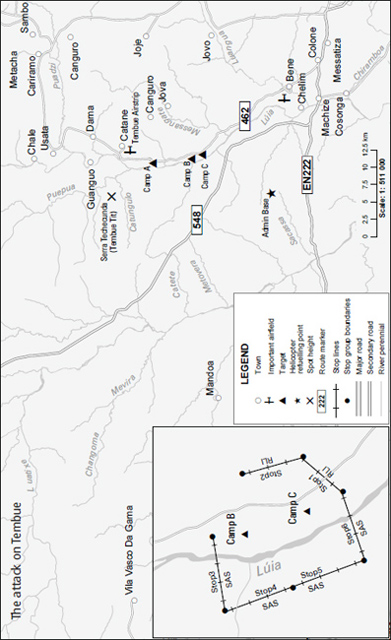

Another ‘door opener’ was Eddy Norris, the moderator of one of the world’s best websites dedicated to ex-servicemen, Old Rhodesian Air Force Sods (ORAFs). Eddy has always been quick and keen to help, pointing me in the right direction and connecting me with many people. One of the first was Rex Taylor, who set up a major helicopter refuelling and transit base during the second phase of Dingo on a mountain in Mozambique known as the Train. Rex made life easy for me by jotting down his experiences, which have certainly added colour to the story.

Peter Stanton, an SB officer who worked closely with Brian Robinson and Scotty McCormack to identify and select the Dingo targets, is gifted with an excellent memory. I am grateful to Peter for shedding light on the mysteries of intelligence gathering, particularly as it related to this story. Another man with an incredible memory is Neill Jackson, a Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) officer during Dingo, who remembers the operation as if it were yesterday. I am grateful to Neill for selflessly sharing his experiences.

I needed to speak to a K-car (helicopter gunship) pilot. PB and Dennis Croukamp immediately pointed me to Mark McLean, a passionate helicopter (and fixed wing) pilot, who took a bullet through his helmet over Chimoio during Dingo. Mark recalled his experiences, particularly as a K-car pilot, with infectious passion and vivid clarity. It was a fascinating interview, enhanced by the wonderful view from the veranda of Mark’s home in Barrydale in the Western Cape.

Steve Kesby, one of the last pilots in the world to fly the de Havilland Vampire in action, vividly depicted the important contribution these super little jets made to Dingo. Derek de Kock, the officer in command of the Parachute Training School, helped me understand the finer details of how paratroopers envelop their target. Darrell Watt, a tough-as-nails SAS officer who was shot at Chimoio, shared that awful moment with me. John Norman of the RLI was also shot at Chimoio, and I am grateful to him for eventually agreeing to talk about it. Through John I got talking to Mark Adams, a fellow troop commander on Dingo, who gave me some great insights. Mark, in turn, connected me, through a book he and Chris Cocks are writing called

Africa’s Commandos: The Rhodesian Light Infantry

, to Simon Haarhoff and Graeme Murdoch, who gave good accounts of their Dingo experiences.

Thanks to Mark Jackson for allowing me to use his photo collection and to Bob Manser for unselfishly trekking around New Farm to take pictures for me of the shrine and some of the gravesites there. Bob Manser also helped me pinpoint exactly where some of the major battles took place.

I am grateful to David Linsell for editing my original script, and for giving me honest and open critique. I would also like to thank Mark Ronan, who edited the final script and whipped the book into shape, as well as correcting some of the Shona words I used.

The final hurdle, especially for a first-time author, is to find a publisher. I was fortunate: the first publisher I sent my manuscript to, Zebra Press at Random House Struik, accepted it. I am grateful to them, and in particular to Robert Plummer, the managing editor, and his team for managing the process of turning

Dingo Firestorm

into a book so professionally and seamlessly.

There are others, too many to mention, who have helped in some way. To you all, my sincere thanks.

And finally, my biggest thanks goes to my wife, Nina, and my family for their love, patience and unwavering support during the research and writing phases, which have taken up a huge chunk of my time over the last few years.

IAN PRINGLE

CAPE TOWN, JANUARY

2012

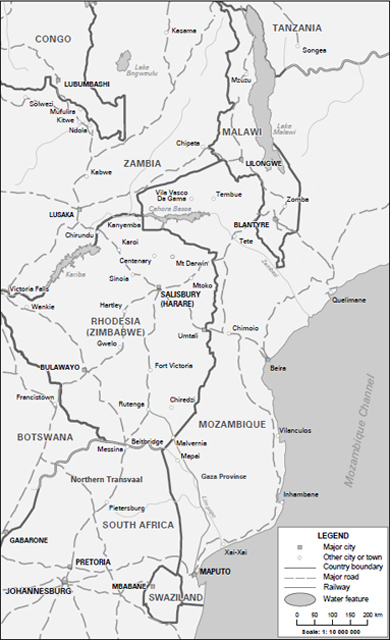

South-east Africa, 1977

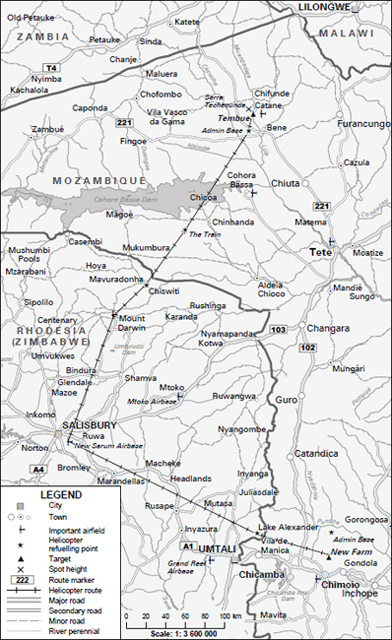

Helicopter routes to Chimoio and Tembue

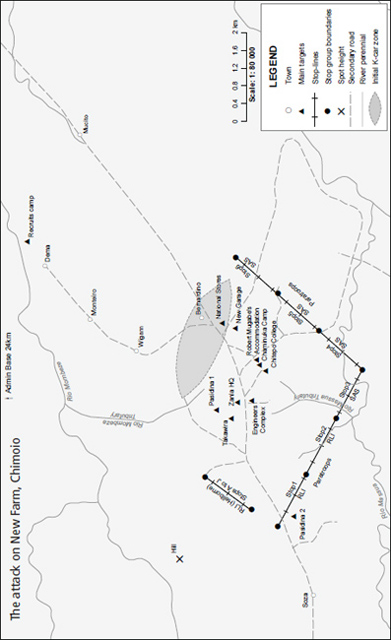

Mozambique, 23 November 1977, 07:42

Lines of white vapour streamed off the wing tips of the speeding Hawker Hunter jet as it turned tightly in the moist, early-morning air. An eerie, haunting howl from the Hunter’s four gaping cannon ports preceded the war machine, shattering the morning calm. Fishermen on the banks of the Pungwe River fled in panic as the jet screeched over their heads at treetop height. The pilot rolled the wings level on a southerly heading, breaking radio silence with a terse transmission: ‘Red 1 at initial point.’

As the jet sped south, the pilot’s eyes darted constantly from the ground to his stopwatch and back to the ever-present ground. As the second hand of the stopwatch touched 17 seconds, the pilot pulled back on the stick and the camouflaged war machine rose majestically into the Mozambican sky, white vapour now pouring off the whole upper-wing area.

The pilot’s vista changed dramatically – he could suddenly see for miles, and there it was, on his left, exactly where he expected it to be: a whitewashed building with a rusty-red roof. He pushed the radio button again and uttered four electrifying words: ‘Red 1 target visual.’

He rolled the jet to his left, almost inverted, not losing sight of the building for an instant. At precisely the right moment, he rolled the Hunter the right way up, the machine now in a perfect 30-degree dive towards the target. As the rusty-red roof started filling the sights, the pilot’s right index finger instinctively found the trigger on the stick – he squeezed it firmly. The jet shuddered violently and slowed as all four cannons fired, sending a hail of deadly 30-mm cannon shells towards the target.