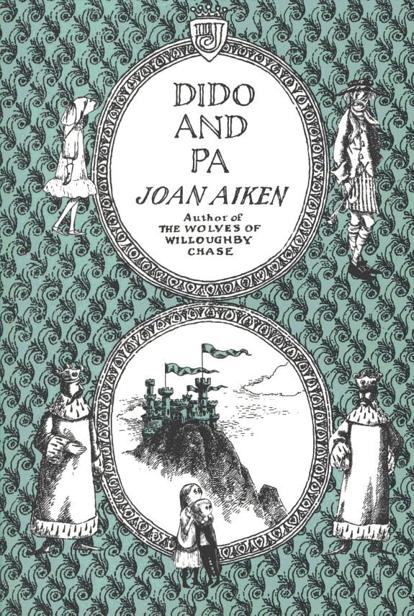

Dido and Pa

Authors: Joan Aiken

Tags: #Action & Adventure, #Fiction, #General, #Juvenile Fiction, #Family, #Fathers and Daughters, #Parents, #Adventure and Adventurers

Joan Aiken

Houghton Mifflin Company

Boston 2003

Copyright © 1986 by Joan Aiken Enterprises, Ltd.

All rights reserved. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, New York 10003.

First printed by Random House UK Ltd. in Great Britain

First American edition published by Delacorte Press, New York

The text of this book is set in 12-point Apollo MT.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 86–2061

Manufactured in the United States of America

HAD 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dusk was closing in over the South Downs on a fine, bitterly cold, windless evening in late November, a hundred years ago, when the driver of a carriage and pair left his horses tied to a gate on the main Chichester-to-London road, vaulted over the gate, crossed a wide, sloping pasture, walked up a chalk track where the wheel ruts showed white in the hazy twilight, and passed through a grove of beech trees.

Overhead the beech leaves, in colors of autumn rust and gold, seemed to glimmer with their own light; down below among the straight tree trunks it was almost dark, and very silent. The single snap of a twig could be heard for a hundred yards, and the good-night squawk of a pheasant in the shadowy woods down below rang out loud as a hunting horn.

By instinct the walker trod with care, to make as little sound as possible. And while he climbed he kept glancing about him alertly, as if he hoped or expected to meet another person.

Beyond the beech grove lay an open space, a saddle-shaped triangle of rough downland turf. Now, in the shadow of a copse on the other side of this little meadow, a second figure could just be glimpsed, coming slowly in the direction of the first one, who called out eagerly:

"Dido—is that you?"

It was not possible to be sure. In the bad light no more could be seen than a smallish, shadowy shape, mooching along rather dejectedly, head bent, hands in pockets.

"Dido?" called the carriage driver again. "Is that you?"

From the small shadowy shape came a kind of astonished croak—not unlike the call of the pheasant: "Simon?" And then, after a pause: "That's never

Simon

? Mussy me—I don't

believe

it!"

Then she hurled herself across the open grassy space. The driver had raced to meet her, and the two collided together, laughing, panting, and hugging one another so energetically that they almost fell over.

"Is it really, really you? Oh, Simon! I reckoned I'd never, ever set eyes on you no more!"

"Hold up, girl—you'll have us in the blackberry bushes!"

"Why, Simon, how you've growed and filled out! Ain't you tall, though!"

"What about yourself? Not that I can see you in this light," he said, laughing, "but you feel twice the size. Puny little brat you used to be—"

"Reckon I growed on account of the whale oil—"

"

Whale oil?

"

"Croopus, Simon, there's such a

deal

to tell you. Oh, I've had such

times

since I saw you last...."

Arm in arm, still hugging one another, they turned back through the beech grove, both talking at once.

"How in the name o' juggernaut did you know I was up here on the hill, Simon?"

"When I looked down this morning from the Whispering Gallery—and saw

Dido Twite

carrying the king's own train—in the coronation procession—you could have knocked me down with a quill. How in the world did

that

come about?"

"That's a long tale—that'd be a deal of long tales.... But if you saw me there in St. Paul's this morning, why in mux's name didn't you let out a holler then, to tell me as you was there?"

"In the middle of the coronation? I sent a message as soon as I could, but you'd gone by then; you see, I had a lot of jobs to do after the service—getting red carpet laid along the street from St. Paul's to St. James's Palace—"

"You gone into the carpet business, then, Simon?" said Dido, stopping in surprise. "I thought you was fixing to be a painter?"

"Oh, I am," he assured her. "But, you see, when Uncle William died—"

"Hold hard! I never knew you had no Uncle Will. Thought you was an orphan?"

"Yes, well, it turned out—You remember the duke of Battersea?"

"Funny old gager in a wig what you used to play chess with?"

"It turned out he was my uncle. So, as he had no children, when he died of the quinsy last winter—that meant I was the next duke."

"Holy mustard!" she exclaimed, thunderstruck. "

You,

Simon? You a dook? Come off it! You're gammoning me!"

"Fact," he assured her. "I'm the sixth duke of Battersea. Loose Chippings Castle in Yorkshire belongs to me—and a big hunk of Battersea—and most of Wessex and East Hum-bria. And, on account of being the duke, that makes me master of the king's garlandries; which meant I had to see to all the decorations for King Richard's coronation, and get the red carpet laid; and a deal of other jobs. I'd just as lief be plain Simon, I can tell you," he ended seriously.

But Dido, whose spirits had shot up as high as they could go, found the notion of her friend being a duke so exquisitely funny that she burst into whoops of laughter. She laughed so much, she had to stand still—indeed, almost fell over, and had to hold on to him, laughing and coughing.

"Oh—that's plummy!" she gasped. "You, a dook! I can remember when you first came riding into Rose Alley on a moth-eaten old moke."

"But where have

you

been all this time, Dido? Last I saw of you—do you remember?—was when the ship sank, and we swam for a rock, and I must have fainted. When I woke, I'd been rescued, but none of the people who rescued me had seen you—or knew anything about you. I thought you

were drowned. So did your Pa. We put up a memorial to you."

"A

memorial

? You never?"

This amused Dido even more. Then she said, more soberly, "I thought as you was drowned too. Lud love us, am I glad you ain't! I got picked up by a whaling vessel, and carried all over—north, south, and rat's ramble; they dumped me on the Isle of Nantucket, and it took a plaguy long time getting back from there; it's umpty thousand miles across the ocean from England. And coming home on a man-o'-war, we had to stop in at a place called New Cumbria—and then, after that, we got muxed up in the Chinese wars. Why, if I was to tell you the

half

of what's been happening to me, I'd be talking till Turpentine Sunday.... So you don't live in Rose Alley no more, now you're a dook?"

"No, my uncle left me a house in Chelsea—Bakerloo House. I live there with Sophie. She turned out to be my sister."

"Well, I'm blest! Come to think," said Dido, "anyone might 'a' guessed it. You're as like as two blackberries—dark hair an' eyes. Why don't you live in Battersea Castle, where the old dook lived?"

"That—er—got blown up...." Simon hesitated tactfully.

"Did my pa and his Hanoverian mates blow it up? I knew they was a-reckoning to, when the old king, the one before this one, came to eat his Christmas dinner with the old dook—"

"Well, yes, they did. And—I'm very much afraid—"

"Ma got blowed up too," said Dido matter-of-factly. "And my aunts, and a whole sackload of other Hanoverians." "How did you know that, Dido?" "I run into my pa a while ago; he'd been a-sculling round here in Sussex, plotting away with a passel o' jammy-fingered coves as reckoned to put a stop to this new king, King Richard, being coronated in St. Paul's. But us put a stop to them," said Dido with satisfaction. "Me and a few gentlemen put some ginger into

their

gravy. I'm right sorry about your castle, though, Simon."

"Oh, it didn't matter," he said quickly. "It was much too big.... Just fancy your running into your pa, though, Dido. Shall you—"

Shall you want to go back and live with him now? was what he had been going to ask. But he stopped—first, because it seemed so unlikely that Dido would want to live with a father who had never taken the least notice of her, or been in any way kind to her; secondly, because, since that father had been mixed up in several Hanoverian plots against the last king and the new one, he would certainly be arrested for treason, if he was spotted by any sheriff or constable, and imprisoned in the Tower of London—and very possibly hanged.

At this moment they reached the road where Simon had left his horses tethered. It was nearly dark, so he pulled out flint and tinder and lit the carriage lamps. They gave but a feeble glimmer, in which he and Dido were able to see not much more of one another than they had on the open hillside. She could vaguely make out that he was bigger, thin-faced as he had always been, with a thatch of untidy black hair; but he was decidedly better dressed than when he had been a humble art student living in her pa's attic and working at night in Cobb's coach yard to pay his school fees. While Simon could dimly see that the puny, undernourished brat, who had teased and provoked him, and stole his dinners, and saved his life, was now a girl of medium height, still very slight, but wiry and active-looking, with short brown hair, and dressed in midshipman's rig of wide blue duffel trousers and a tight-fitting pea jacket with brass buttons. The pea jacket was very thin and worn.

"Murder but it's getting cold," shivered Dido as she scrambled into the curricle.

"Winter's almost here," said Simon. "They say it's going to be a hard one, and come early. It might snow tonight; feels like a frost for sure. You'll not be warm enough on the drive to London dressed like that, Dido. We'll stop in Petworth and buy you a sheepskin or something to wrap up in."

"I'd not say no to a bit of nosh, neither; haven't had a smidgen all day. We didn't stop for the junketings after the crowning; one o' my mates as helped carry the king's train was anxious to get back to his sick dad here in Petworth."

"We'll have a bite of supper, then, before starting; I have to change horses too. Then we'll go to Bakerloo House. Sophie will be

so

happy to see you, Dido."

Without the need for words, it had been accepted between them that Dido would stay in Simon's house; even if he were a duke.

***

In the courtyard of Simon's house in Chelsea, a group of ragged children had collected and begun to play a game. The house was an old one, built of crumbling stone; the courtyard, which opened onto the King's Road, was about the size of a tennis court and had a stone fountain in the middle, very useful for dancing rings round.

But the children were not dancing rings at the moment. They had formed themselves into two long lines and leaned toward one another, hands on the opposite person's shoulders.

They sang:

"

Dig a tunnel, sink a mine,

Under and out the other side.

Dig a tunnel, sink a drain.

In goes the king with his golden train.

"

At this point two players, from opposite ends of the line, turned and ran under all the arching arms, passing each other in the middle.

"

Who comes out?

Little Tommy Stout!

Ha ha ha, hee, hee, hee,

You're not the one I thought to see!

"

Faster and faster ran the players, peeling off the end of the rank, diving under the arch, squeezing past each

other in the middle, then joining on at the other end. There seemed little point to the game, except its skill and speed.

"Hey, all you young scaff and raff!" roared Fidd the porter, coming out of his lodge. "Clear off! Clear off, I say! We don't want your like in here!"

They laughed and jeered at Fidd but slowly began to obey him. Just as the last few were skipping out of the big double gates, thumbing their noses at the porter, Lady Sophie Bakerloo rode in from the other direction on a small, skittish mare. She was very pretty, with dark curls and eyes; she wore a fur-lined riding cape.

"What is it, Fidd, what's the matter?" she called.

"Them owdacious young 'uns," he grumbled. "Playing their capsy games in our yard..."

"But I like to see them, Fidd!"

A small lavender seller, who had put down her tray of bunches and lavender bags while she played, now passed Sophie, settling the strap again round her neck.

"I'll take two of your lavender bags, my love," Sophie called to her, and the girl curtsied, beaming.

"Thank-ee, my lady! They're a saltee for three, or a mag apiece."

"Then I'll have three," said Sophie, and gave her a penny.

"Walker!" exclaimed the little creature. "Now four o' my mates'll have the money for a lollpoops' lodging! It's a farden apiece."

"But what about yourself, my dear?"

"Oh,

I'm

took care of.

I've

got a dad. But in the Birthday League we all looks out for each other."

"The Birthday League—what is that?"

"When's your birthday, my lady?"

"The tenth of April."

"Mine's the fifth o' Febry. Now you're a member!" said the small lavender seller, and skipped away as Sophie stared after her, raising her small clear voice in a lusty shout of "Swe-e-e-e-et Lavende-e-e-e-er!"