Dickinson's Misery (12 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Thus one difficulty for critical thinking about the lyric is that a contingent, developmental view of genre is so intimately tied to the novel that the lyric becomes the novel's other, assigned to an outmoded stylization rather than a dynamic process. The other side of this difficulty is that in fact the lyricization of poetry works very differently than the novelization of genre: whereas novelization has made genre a more socially enmeshed concept, lyricization has taken traditional poetic genres out of circulation. When Clifford Siskin writes that “the lyricization of the novel” began in Austen, for example, he means to argue that the historicity of genre makes

all genres intergenericâthat is, that the romantic lyric influences the nineteenth-century novel and that the novel influences the lyric. It is certainly true that, as Siskin states, “poetry and the novel ⦠cannot be known in isolation from each other” in the nineteenth century, but postromantic lyric discourse shapes another view of genre altogether: when we read a text as a lyric, we consent to take it out of circulation and, in a sense, out of generic contingency.

52

If the novel is the modern genre par excellence because it takes all genres into itself and celebrates generic contingency, lyric is the modern antigenre, since it is at once too formally distinct to be anything other than a literary genre, and yet it pretends not to be any particular literary genre. John Stuart Mill, the touchstone theorist of the lyric in Anglo-American modernity, makes the intentional performance of such an illusion explicit in a passage that immediately follows his famous distinction between eloquence as

heard

and poetry as

overheard,

a distinction that defines all poetry as “soliloquy”: “It may be said that poetry which is printed on hot-pressed paper and sold at a book-seller's shop, is a soliloquy in full dress, and on the stage. It is so; but there is nothing absurd in the idea of such a mode of soliloquizingâ¦. The actor knows that there is an audience present; but if he act as though he knew it, he acts ill.”

53

According to Mill, the circulation of poetry “on hot-pressed paper” is exactly what the generic conventions of the lyric cannot acknowledgeâthat is, the lyric can no more acknowledge its literal circumstance than can the actor, and is at the same time no less dependent than that actor on the generic recognition of the audience it must pretend is not there. Thus the difficulty of thinking about the lyric as implicated in historical contingency is that the discourse that surrounds the genre must admit without acknowledging the defining effect of that contingency.

Dickinson's lines on the envelope in

figure 5

both exemplify and ponder the difficulty of thinking through lyric historicity, of shifting the lyric archive. If “a Blue Bird's tuneâ” is, as I have suggested, a figure for lyric convention, then the question that the lines pose is a question of their own survival. Since they have not survived as a lyric on hot-pressed paper, we might conclude that they fail to answer the question. Certainly the lines that offer various figures for lyric survival amplify rather than solve the problem: the ephemerality of birdsong by definition does not last, but Resurrection is, by definition, what does. In Dickinson's version, however, recognition is what Resurrection “had to wait” for; the stone is moved not in order to allow Christ's body to escape (that has already been accomplished by unseen hands) but so that the apostles can witness its disappearance. As in Mill's figure of the actor's soliloquy, in Dickinson's figure of the historical contingency of the Resurrection, the public confers definition. Or does it? If drumbeats play to the dead (whether they have been

resurrected or not), then their audience (not incidentally, the victims of public violence) cannot recognize them. The lines on the right flap of the envelope (

fig. 5

) acknowledge that the double bind of lyric circulation suspends the writer's address to the reader between mutually exclusive poles: if “I dare not / write until / I hearâ” what the generic conditions for reading what I write might be, then the lines depend on an afterlife of translation. Uncertain of that afterlife, the lines remain in temporal suspension: “Intro without / my Transâ.” Indeed, their afterlife has depended on a series of historically contingent versions of lyric reading, including the reading I have just performed. Yet until I just dared to write that these lines take up the subject of lyricism itself, they had not been translated into the lyric they claim they cannot become.

Since self-reflexiveness is one of the central criteria of lyric discourse, my reader might say that I have just done exactly what I set out not to do: I have made an old envelope into a new Dickinson lyric. Despite my intention to read it as an envelope, I have interpreted it as a lyricâindeed, I have made it a metalyric. Thus we might conclude that the reason for us to think that Dickinson wrote lyric poems is that even though she did not publish most of her work on hot-pressed paper as a series of lyric soliloquies, an envelope never published as a lyric can be interpreted as such. Further, the historical accidents that have kept this manuscript from publication make it the figure of the lyric par excellence: the soliloquy we now “hear” because it was definitely not performed for us. On this view, genre is a consequence of interpretation (the writer may

act

as if her writing is not addressed to us, but it is up to us, as sophisticated readers of the genre, to know that it is). But it is precisely this discourse of lyric interpretation that Dickinson's lines on the envelope query. What makes such interpretation possible? Fundamentally, a lyric reading practice supposes that poems are written in view of a future horizon of interpretation, a “Transâ.” Everything about Dickinson's work contradicts that supposition: either she actually sent lines to friends or she wrote them on household scraps like the split-open envelope. Yet as Cameron suggests, the fascicles are the exception to both rules; if Dickinson made books, then was she not indulging in a form of self-publication in view of future or at least imaginary readers of those books?

If we think of the fascicles as books of poems, then the discourse of lyric reading would dictate that we answer yes to that question. After Lavinia Dickinson found the sheets tied with string in Dickinson's bedroom after her death, she called them “volumes”; Mabel Loomis Todd, Higginson's editorial collaborator (and the person who did all the practical editorial work, as her daughter, also a Dickinson editor, would point out) coined the term “fascicles” (often, “little fascicles”), preferring the botanical term

for a bundle of stems or leaves to Lavinia's image of a series of bound books.

54

Lavinia's assumption from the beginning was that if the pages tied with string were “volumes,” then the writing within them must be “poems,” and that while other manuscripts might be personal and therefore should be destroyed upon the death of the person (she had already burned hundreds), poems in books were intended for print.

55

Cameron's argument that the fascicles are “definitive, if privately published texts” extends Lavinia's assumption that poems should be treated as if intended for publication, though as we have seen, Cameron suggests that Dickinson sought to expand the possibilities of the lyric by not printing, and so not choosing, individual lyrics. But what if the fascicles areâor wereânot books at all, or not “volumes” either meant for or kept from publication? If not, would that mean that the writing inside them is neither a series of lyrics nor one big lyric?

When Higginson introduced Dickinson's

Poems

in 1890 by writing that her verses “belong emphatically to what Emerson has long since called âthe Poetry of the Portfolio,' ” he was referring to Emerson's suggestion in 1840 that there be “a new department in poetry, namely,

Verses of the Portfolio.

”

56

With Emerson's phrase Higginson took Emerson's lyrical notion that “manuscript verses” exhibited “the charm of character,” that they were “confessions ⦠for they testified that the writer was more man than artist, more earnest than vain”âthat is, that the writer of such verses was Mill's perfect actor, utterly unaware of his audience. Yet the majority of portfolio makers in New England in the nineteenth century were women who did not write with a view toward or away from publication; rather, the many forms of the portfolio in the period tended to take the materials of the culture into the literate life of the private individual. Barton Levi St. Armand has pointed out “the essentially private nature of the portfolio genre, its function as a loose repository of musings, views, portraits, copies, caricatures, and âstudies from nature' that made it truly an idiosyncratic âBook of the Heart.' The portfolio ⦠had close affinities with the schoolgirl exercises of the album, the herbarium (in which Dickinson was adept), and the scrapbook.”

57

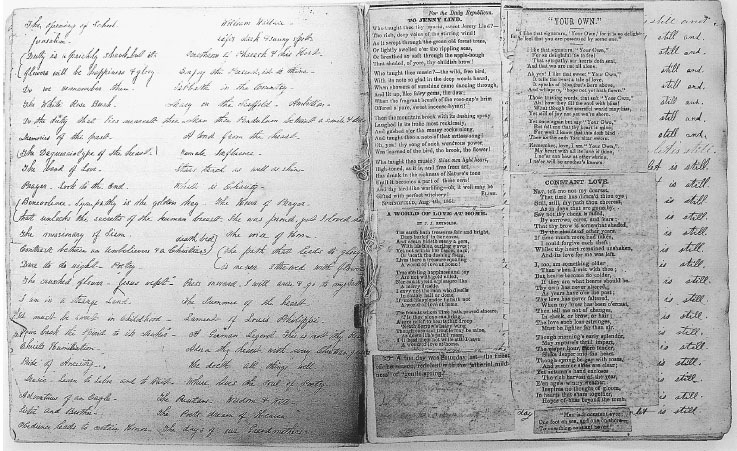

Although St. Armand dubs such collections “private,” it is important to note that such privacy literally included publicly circulated material; in many instances, the copybook practice typical of school albums consisted of writing out poems already in print, or of pasting printed poems beside manuscript copies. In the handsewn school notebook of Georgina M. Wright, for example (

fig. 9

), Mount Holyoke Female Seminary Class of 1852, class notes face a page of handwriting exercises partially obscured by pasted poems cut from the newspaper (the same weekly local paper in which Dickinson's poems would first appear). Dickinson attended Mount Holyoke in 1847 and 1848, and though her school notebooks probably went up in Lavinia's fire, the habit of sewing pages together to create manuscript books would have been part of her practice there. Like other things at Mount Holyoke, it was a practice that extended domestic culture into the school; as the facing pages from a notebook kept by members of the Page family in Boston between 1823 and 1827 illustrate (

figure 10

), the domestic transcription of poetry resembled school exercisesâjust as school exercises resembled domestic literacy.

58

Both also resemble the fasciclesâso much so that we may conclude that such collections are not

like

the fascicles, but are what the pages now called “Dickinson's fascicles”

are

âor

were.

That difference in temporal definition is a difference in genre: if lyrics are private performances in public, “sudden flashes” of present-tense immediacy, and utterances addressed to future interpreters, then Dickinson's manuscripts are not lyrics. Though the fascicles were for the most part, as far as we know, collections of Dickinson's own verse, they were collections from different occasions, various correspondences. They undo each criterion of lyric discourse by reversing it: they take public materials into privacy; their material, artifactual circumstances and, often, their figurative content emphasize temporal difference rather than simultaneity; if they are now addressed to literary interpreters, Dickinson is not the one who inscribed the envelope.

Figure 9. Notebook of Georgina M. Wright, Mount Holyoke Female Seminary Class of 1852. Courtesy of Mount Holyoke College and Special Collections.

Yet if even such a fragmentary critical archaeology suggests that Dickinson's writing undoes lyric discourse, it also suggests that Dickinson's writing has come to epitomize lyricism by being removed from its circumstances of circulation by unseen editorial hands. It may seem funny to insist on Dickinson's private (or non-)circulation of her own writing as an historical condition of generic exchange, but Cameron, Howe, Smith, Werner, and others who urge editorial revision of the Dickinson canon are right to point out that the difference between the isolated Dickinson lyric in print and the experience of reading Dickinson's intricate manuscript compositions changes one's view of the writing in ways we have yet to explain. As we saw in the instance of the

HOME INSURANCE CO. NEW YORK

memo pages (

figs. 7a

,

7b

), part of that difference depends on the surplus value of literal context the manuscripts provide: lines from Swinburne may appear in excerpted, lyricized form beside what seem to be personal notes or parts of a letter, but editors like Shurr and Franklin can find quatrains and couplets in even such riddled manuscripts. Yet in removing such lines from their historical “text occasions,” editors have also changed the way in which we read them. In print editions, lines such as “the Affluence / of time” or “Loves / dispelled / Emolument” may appear invitations to metaphorical translation, evidence of Dickinson's famous blend of abstract and concrete nouns, of economic and poetic terms, of suggestively inappropriate prepositions and verb forms. In the textual economy of the memo sheets, however, “Emolument” and “Affluence” pun on the insurance company's ad. The agent of the company's “Cash Assets, over

SIX MILLION DOLLARS

” may promise one sort of affluence, and the payments the agent offers constitute one sort of emolument, “but Loves / dispelled / Emolument” is, by contextual implication, uninsured.

59

The distribution of such memo sheets to wealthy private home owners like the Dickinsons represented the implication of public business enterprise in domestic private life, a symptom of the development of what Gillian Brown has dubbed American “domestic individualism.”

60

As the manuscript books enfolded home into school and school into the home, Dickinson's use of the memo sheets as writing material turned the public appropriation of privacy inside out. Not incidentally, at least some of the lines on the sheets claim that “Love,” that most cherished of domestic sentiments, is not subject to claims of capital and commodityâthough the sheet on which those claims are written may be.