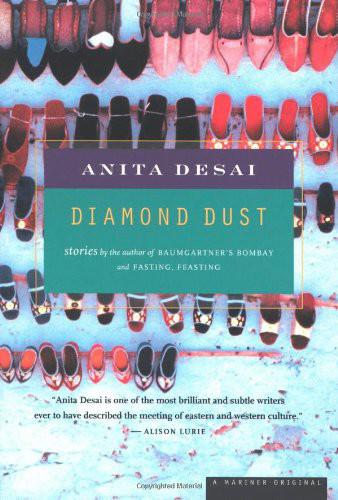

Diamond Dust

Authors: Anita Desai

| Diamond Dust |

| Anita Desai |

| Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2012) |

Upon the recent publication of Fasting,

Feasting, critics raved about Anita Desai: "Desai is more than smart; she's an

undeniable genius" (Washington Post Book World). The Wall Street Journal called

Fasting, Feasting "poignant, penetrating . . . a splendid novel, " while the

Boston Globe celebrated Desai's "beautiful literary universe." Now, in this

richly diverse collection, Desai trains her luminous spotlight on private

universes, stretching from India to New England, from Cornwall to Mexico.

Skillfully navigating the fault lines between social obligation and personal

loyalties, the men and women in these nine tales set out on journeys that

suddenly go beyond the pale -- or surprisingly lead them back to where they

started from. In the mischievous title story, a beloved dog brings nothing but

disaster to his obsessed master; in other tales, old friendships and family ties

stir up buried feelings, demanding either renewed commitment or escape. And in

the final exquisite story, a young woman discovers a new kind of freedom in

Delhi's rooftop community.

With her trademark "perceptiveness, delicacy of

language, and sharp wit" (Salman Rushdie) in full evidence here, Anita Desai

once again gloriously confirms that she is "India's finest writer in English"

(Independent).

STORIES

Anita Desai

A Mariner Original

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

BOSTON • NEW YORK

2000

Copyright © 2000 by Anita Desai

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York,

New York 10003.

Visit our Web site:

www.hmco.com/trade

.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

data is available.

ISBN

0-618-04213-x

First published in Great Britain in 2000

by Chatto & Windus

Printed in the United States of America

QUM

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

AcknowledgementsTo my students at M.I.T.

who have been my teachers

Many thanks to the Civitella Ranieri Foundation for providing me with a summer in Umbria where I revised these stories. The author and publisher are grateful to New Directions and Carcanet Press for permission to reproduce the extracts from 'In Uxmal' and 'Exclamation' from

Selected Poems

by Octavio Paz and

The Collected Poems of Octavio Paz, 1957—1987

respectively, quoted on pages 148 and 154 of 'Tepoztlan Tomorrow'.

Royalty

[>]

Winterscape

[>]

Diamond Dust,

a Tragedy

[>]

Underground

[>]

The Man Who Saw Himself Drown

[>]

The Artist's Life

[>]

Five Hours to Simla

or

Faisla

[>]

Tepoztlan Tomorrow

[>]

The Rooftop Dwellers

[>]

A

LL

was prepared for the summer exodus: the trunks packed, the household wound down, wound up, ready to be abandoned to three months of withering heat and engulfing dust while its owners withdrew to their retreat in the mountains. The last few days were a little uncomfortable—so many of their clothes already packed away, so many of their books and papers bundled up and ready for the move. The house looked stark, with the silver put away, the vases emptied of flowers, the rugs and carpets rolled up; it was difficult to get through this stretch, delayed by one thing or another—a final visit to the dentist, last instructions to the stockbrokers, a nephew to be entertained on his way to Oxford. It was only the prospect of escape from the blinding heat that already hammered at the closed doors and windows, poured down on the roof and verandas, and withdrawal to the freshness and cool of the mountains which helped them to bear it. Sinking down on veranda chairs to sip lemonade from tall glasses, they sighed, 'Well, we'll soon be out of it.'

In that uncomfortable interlude, a postcard arrived—a cheap, yellow printed postcard that for some reason to do with his age, his generation, Raja still used. Sarla's hands began to tremble: news from Raja. In a quivering voice she asked for her spectacles. Ravi passed them to her and she peered through them to decipher the words as if they were a flight of migrating birds in the distance: Raja was in India, at his ashram in the south, Raja was going to be in Delhi next week, Raja expected to find her there. She

would

be there, wouldn't she? 'You won't desert me?'

After Ravi had made several appeals to her for information, for a sharing of the news, she lifted her face to him, grey and mottled, and said in a broken voice, 'Oh Ravi, Raja has come. He is in the south. He wants to visit us—next week.'

It was only to be expected that Ravi's hands would fall upon the table, fall onto china and silverware, with a crash, making all rattle and jar. Raja was coming! Raja was to be amongst them again!

A great shiver ran through the house like a wind blowing that was not a wind so much as a stream of shining light, shimmering and undulating through the still, shadowy house, a radiant serpent, not without menace, some threat of danger. Whether it liked it or not, the house became the one chosen by Raja for a visitation, a house in waiting.

With her sari wrapped around her shoulders tightly, as if she were cold, Sarla went about unlocking cupboards, taking out sheets, silver, table linen. Her own trunks, and Ravi's, had to be thrown open. What had been put away was taken out again. Ravi sat uncomfortably in the darkened drawing room, watching her go back and forth, his lips thin and tight, but his expression one of helplessness. Sometimes he dared to make things difficult for her, demanding a book or a file he knew was at the very bottom of the trunk, pretending that it was indispensable, but when she performed the difficult task with every expression of weary martyrdom, he relented and asked, 'Are you all right? Sarla?' She refused to answer, her face was clenched in a tightly contained storm of emotion. Despondently, he groaned, 'Oh, aren't we too old—?' Then she turned to look at him, and even spoke: 'What do you mean?' Ravi shook his head helplessly. Was there any need to explain?

Raja arrived on an early morning train. Another sign of his generation: he did not fly when he was in India. Perhaps he had not taken in the fact that one could fly in India too, or else he preferred the trains, no matter how long they took, crawling over the endless, arid plains in the parched heat before the rains. At dawn, no sun yet visible, the sky was already white with heat; crows rose from the dust-laden trees, cawing, then dropped to the ground, sun-struck. Sweepers with great brooms made desultory swipes at the streets, their mouths covered with a strip of turban, or sari, against the dust they raised. Motor rickshaws and taxis were being washed, lovingly, tenderly, by drivers in striped underpants. The city stank of somnolence, of dejection, like sweat-stained clothes. Sarla and Ravi stood on the railway platform, waiting, and when Sarla seemed to waver, Ravi put out a gentlemanly hand to steady her. When she turned her face to him in something like gratitude or pleading, a look passed between them as can only pass between two people married to each other through the droughts and hurricanes of thirty years. Then the train arrived, with a great blowing of triumphant whistles: it had completed its long journey from the south, it had achieved its destination, hadn't it

said

it would? Magnificently, it was a promise kept. Immediately, coolies in red shirts and turbans, with legs like ancient tree roots, sprang at the compartments, leaping onto the steps before the train had even halted or its doors opened, and the families and friends waiting on the platform began to run with the train, waving, calling to the passengers who leaned out of the windows. Sarla and Ravi stood rooted to one place, clinging to each other in order not to be torn apart or pushed aside by the crowd in its excitement.

The pandemonium only grew worse when the doors were unlatched and the passengers began to dismount at the same time as the coolies forced their way in, creating human gridlock. Sighting their friends and relatives, the crowds on the platform began to wave and scream. Till coolies were matched with baggage, passengers with reception parties, utter chaos ruled. Sarla and Ravi peered through it, turning their heads in apprehension. Where was Raja? Only after the united families began to leave, exhorting coolies to bring up the rear with assorted trunks, bedding rolls and baskets balanced on their heads and held against their hips, and the railway platform had emerged from the scramble, did they hear the high-pitched, wavering warble of the voice they recognised: 'Sar-la! Ra-vi! My dears, how

good

of you to come! How

good

to see you! If you only knew what I've beeen through, about the man who insisted on telling me about his

alligator

farm, describing at such length how they are turned into

handbags,

as though I were a

leather merchant

...' and they turned to see Raja stepping out of one of the coaches, clutching his silk dhoti with one hand, waving elegantly with the other, a silver lock of his hair rising from his wide forehead as he landed on the platform in his slippered feet. And then the three of them were embracing each other, all at once, and it might have been Oxford, it might have been thirty years ago, it might even have been that lustrous morning in May emerging from dew-drenched meadows and the boat-crowded Isis, with ringing out of the skies and towers above them—bells, bells, bells, bells....

'And then there was

another

extraordinary passenger, a young man with hair like a nest of serpents, you know, and when he understood I would

not

eat a "two-egg mamlet" offered to me by this

incredibly

ragged and

totally

sooty little urchin with a tin tray under his arm, nor even a "

one-egg

mamlet" to please him or anyone, this marvellous person leapt down from the bunk above my head, and shot out of the door—oh, I assure you we were at a standstill, in the most

desolate

little station imaginable, for no reason I could see or guess at if I cudgelled my brains ever so

ferociously

— and then he returned with a basket

overflowing

with fruit, a positive

cornucopia.

Sarla, you'd have

fainted

with bliss! Never did you see such fruit; oh, nowhere, nowhere on those mythical farms of California, certainly, worked on by those armies of the exploited from the sad lands to the south, I assure you, Ravi, such fruit as seemed a reincarnation of the fruit one ate as a child,

stolen

, you know, from the neighbour's orchard, fruit one ate hidden in the

darkest

recesses of one's compound, surreptitiously, one's tongue absolutely

shrivelled

by the

piercing

sweetness of the mangoes, the

cruel

tartness of unripe guavas, the unripe pulp of the plantains. Oh, Sarla, such joys! And I sat peeling a

tiny

banana and eating it—it was no bigger than my little finger and contained the flavour of the ripest, sweetest, best banana anywhere on earth within its cunning little yellow speckled jacket—I asked, naturally, what I owed him. But that incredible young man, who looked something like a cornucopia

himself,

with that abundant hair—it had such a quality of

liveliness

about it, every strand almost

electric

with energy—he merely folded his hands and said he would not take one paisa from me, not

one. Well

, of course I pushed away the basket and said I could not possibly accept it, totally against my principles, etcetera, and he gave me this tender, tender smile, quite unspeakably loving, and said he could take nothing from me because in a previous incarnation I had been his grandfather: he recognised me. "What?" said I, "

what

? What makes you say so? How

can

you say so?'"

'Watch out!' Ravi shouted at the driver who overtook a bullock cart so closely he almost ran into its great creaking wheels and overturned it.

'And he merely smiled, this sweet,

ineffably

sweet smile of his, and assured me I was no other than this esteemed ancestor of his who had left his home and family at the age of fifty and gone off into the Himalayas to live as a hermit and meditate. "

Well

" said I—'

'Slow down,' Ravi ordered the driver curtly.

'"Well

" said I, "I

assure

you I have never been in the Himalayas—although it is

indeed

my life's ambition to do so, and therefore I could not have returned from there." By the way, I began to wonder if it was

altogether

flattering to be called grandfather by a man by no means in the first flush of youth, more like the becalmed middle years, whereupon he told me—imagine, Sarla, imagine, Ravi—he told me his grandfather had

died

there, in Rishikesh, on the banks of the Ganga, many years ago. His family had all travelled up from Madras to witness the cremation and carry the ashes to Benares, but

now,

in the railway carriage, that little tin box

baking

in the sun as we crossed the red earth and ravines of Central India, he claimed he'd seen his reincarnation. He was as

certain

of it as the banana in my hand was a banana! He would not tell me

why

, or

how

, but he was clearly a clairvoyant. And isn't that a

superb

combination: clearly clairvoyant! Or do you think it a touch

de trop

? Hmm, Ravi, Sarla?'