Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes (59 page)

Read Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes Online

Authors: Tamim Ansary

BOOK: Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes

11.12Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

And I must say, I don’t see how a single society can be constructed in which some citizens think the whole world should be divided into a women’s realm and a men’s realm, and others think the genders should be blended into a single social realm wherein men and women walk the same streets, shop the same shops, eat at the same restaurants, sit together in the same classrooms, and do the same jobs. It can only be one or the other. It can’t be both. From where I stand, I don’t see how Muslims can live in the West, under the laws and customs of Western societies, if they embrace

that divided-world view, nor how Westerners can live in the Muslim world as anything but visitors, if they embrace that genders-shuffled-together view.

that divided-world view, nor how Westerners can live in the Muslim world as anything but visitors, if they embrace that genders-shuffled-together view.

I don’t offer one answer or another to the questions I am posing. I only say that Muslim intellectuals have to grapple with them. And they

have

been. Some of the most daring departures from orthodox Islamic doctrines emerged in Iran, during the two decades after that country expelled the United States and claimed its cultural sovereignty. There, anonymous writers proposed that every generation had the right to interpret the Shari’ah anew without reference to the accumulated code of the religious scholars. This idea and others like it were suppressed. The suppression made news in the West—i

t was more evidence that Iran was

not a democracy.

What struck me, however, was that such ideas were voiced at all in the Muslim world. I wondered if it could only happen in a place where Muslims were struggling with themselves and each other, not with the West.

have

been. Some of the most daring departures from orthodox Islamic doctrines emerged in Iran, during the two decades after that country expelled the United States and claimed its cultural sovereignty. There, anonymous writers proposed that every generation had the right to interpret the Shari’ah anew without reference to the accumulated code of the religious scholars. This idea and others like it were suppressed. The suppression made news in the West—i

t was more evidence that Iran was

not a democracy.

What struck me, however, was that such ideas were voiced at all in the Muslim world. I wondered if it could only happen in a place where Muslims were struggling with themselves and each other, not with the West.

After 9/11 the Bush administration ratcheted up the pressure on Iran, and in the face of this external threat, ideas with a Western aroma lost credibility because they smelled of collaboration: they no longer needed to be suppressed; they could gain no purchase with a public that had turned conservative, a public that chose the ultranationalist Ahmadinejad to head up their nation.

Many points for discussion, even argument, simmer between the Islamic world and the West. There can be no sensible argument, however, until both sides are using the same terms and mean the same things by those terms—until, that is, both sides share the same framework or at least understand what framework the other is assuming. Following multiple narratives of world history can contribute at least to developing such a perspective.

Everybody likes democracy, especially as it applies to themselves personally; but Islam is not the opposite of democracy; it’s a whole other framework. Within that framework there can be democracy, there can tyranny, there can be many states in between.

For that matter, Islam is not the opposite of Christianity, nor of Judaism. Taken strictly as a system of religious beliefs, it has more areas of agreement than argument with Christianity and even more so with Judaism—take a look sometime at the laws of diet, hygiene, and sexuality prescribed by orthodox religious Judaism, and you’ll see almost exactly the same list as you find in orthodox, religious Islam. Indeed, as Pakistani writer Eqbal Ahmad once noted, until recent centuries, it made more sense to speak of Judeo-Muslim than of Judeo-Christian culture.

It is, however, problematically misleading to think of Islam as one item in a class whose other items are Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, etc. Not inaccurate, of course: Islam

is

a religion, like those others, a distinct set of beliefs and practices related to ethics, morals, God, the cosmos, and mortality. But Islam might just as validly be considered as one item in a class whose other items include communism, parliamentary democracy, fascism, and the like, because Islam is a social project like

those

others, an idea for how politics and the economy ought to be

managed, a complete system of civil and criminal law.

is

a religion, like those others, a distinct set of beliefs and practices related to ethics, morals, God, the cosmos, and mortality. But Islam might just as validly be considered as one item in a class whose other items include communism, parliamentary democracy, fascism, and the like, because Islam is a social project like

those

others, an idea for how politics and the economy ought to be

managed, a complete system of civil and criminal law.

Then again, Islam can quite validly be seen as one item in a class whose other items include Chinese civilization, Indian civilization, Western civilization, and so on, because there is a universe of cultural artifacts from art to philosophy to architecture to handicrafts to virtually every other realm of human cultural endeavor that could properly be called Islamic.

Or, as I have tried to demonstrate, Islam can be seen as one world history among many that are unfolding simultaneously, each in some way incorporating all the others. Considered in this light, Islam is a vast narrative moving through time, anchored by the birth of that co

mmunity in Mecca and Medina fourteen centuries ago. The story includes many characters who are not Muslim and many events that are not religious. Jews and Christians and Hindus are part of this story. Industrialization is an element of the plot, and so is the steam engine and the discovery of oil. When you look at it this way, Islam is a vast complex of communal purposes moving through time, driven by its own internally coherent assumptions.

mmunity in Mecca and Medina fourteen centuries ago. The story includes many characters who are not Muslim and many events that are not religious. Jews and Christians and Hindus are part of this story. Industrialization is an element of the plot, and so is the steam engine and the discovery of oil. When you look at it this way, Islam is a vast complex of communal purposes moving through time, driven by its own internally coherent assumptions.

And so is the West.

So which is the

real

history of the world? The philosopher Leibniz once posited the idea that the universe consists of “monads,” each monad being the whole

universe understood from a particular point of view, and each monad containing all the others. World history is like that: the whole story of humankind from a particular point of view, each history containing all the others, with all actual events situated somewhere with respect to a central narrative, even if that “somewhere” is in the background as part of the white noise against which the meaningful line stands out. They’re all the real history of the world. The work lies in the never-ending task of compiling them in the quest to build a universal human community situated within a singl

e shared history.

real

history of the world? The philosopher Leibniz once posited the idea that the universe consists of “monads,” each monad being the whole

universe understood from a particular point of view, and each monad containing all the others. World history is like that: the whole story of humankind from a particular point of view, each history containing all the others, with all actual events situated somewhere with respect to a central narrative, even if that “somewhere” is in the background as part of the white noise against which the meaningful line stands out. They’re all the real history of the world. The work lies in the never-ending task of compiling them in the quest to build a universal human community situated within a singl

e shared history.

APPENDIX

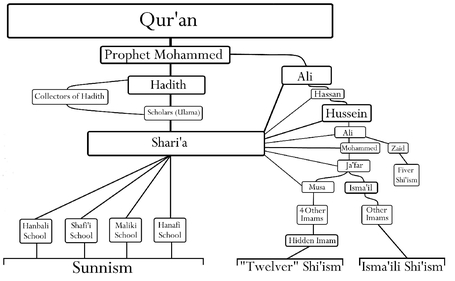

The Structure of Isla

mic Doctrine

mic Doctrine

NOTES

INTRODUCTION1

With footnotes.

CHAPTER 1With footnotes.

2

Conan Doyle, for example, uses “Parthian shot” to mean “parting shot” in his 1886 novel

A Study in Scarlet

.

Conan Doyle, for example, uses “Parthian shot” to mean “parting shot” in his 1886 novel

A Study in Scarlet

.

3

The eleventh-century Persian poet Firdausi drew on this vast body of Persian legends to write the

Shahnama

(The Book of Kings), an epic poem in which Kay Khosrow the Just figures largely.

CHAPTER 2The eleventh-century Persian poet Firdausi drew on this vast body of Persian legends to write the

Shahnama

(The Book of Kings), an epic poem in which Kay Khosrow the Just figures largely.

1

From a passage by Tabari, excerpted in

The Inner Journey: Views from the Islamic Tradition,

edited by William Chittick, (Sandpoint, Idaho: Morning Light Press, 2007), p. xi.

From a passage by Tabari, excerpted in

The Inner Journey: Views from the Islamic Tradition,

edited by William Chittick, (Sandpoint, Idaho: Morning Light Press, 2007), p. xi.

2

Akbar Ahmed’s

Islam Today

(New York and London: I. B. Tauris, 1999), p. 21, for excerpts from Mohammed’s last sermon.

CHAPTER 3Akbar Ahmed’s

Islam Today

(New York and London: I. B. Tauris, 1999), p. 21, for excerpts from Mohammed’s last sermon.

2

This is Tabari’s description; an excerpt appears on page 12 of

Islam: From the Prophet Mohammed to the Capture of Constantinople

, a collection of documents edited and translated by Bernard Lewis. (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

This is Tabari’s description; an excerpt appears on page 12 of

Islam: From the Prophet Mohammed to the Capture of Constantinople

, a collection of documents edited and translated by Bernard Lewis. (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

3

The core of a document purporting to be Omar’s original declaration to Jerusalem appears in Hugh Kennedy’s

The Great Arab Conquests

(New York: Da Capo Press, 2007), pp. 91-92.

CHAPTER 5The core of a document purporting to be Omar’s original declaration to Jerusalem appears in Hugh Kennedy’s

The Great Arab Conquests

(New York: Da Capo Press, 2007), pp. 91-92.

1

From Ibn Qutayba’s ninth-century history

Uyun al-Akhbar,

excerpted in

Islam: From the Prophet Muhammed to the Capture of Constantinople

(New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 273.

From Ibn Qutayba’s ninth-century history

Uyun al-Akhbar,

excerpted in

Islam: From the Prophet Muhammed to the Capture of Constantinople

(New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 273.

2

Nafasul Mahmum

(chapter 14), Sheikh Abbas Qummi quoting from thirteenth-century historian Sayyid Ibn Tawoos’s book

Lahoof

(Qom, Iran: Ansariyan Publications, 2005).

CHAPTER 6Nafasul Mahmum

(chapter 14), Sheikh Abbas Qummi quoting from thirteenth-century historian Sayyid Ibn Tawoos’s book

Lahoof

(Qom, Iran: Ansariyan Publications, 2005).

2

From

Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census

by Tertius Chandler. (Lewiston, New York: St. David’s University Press, 1987).

CHAPTER 7From

Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census

by Tertius Chandler. (Lewiston, New York: St. David’s University Press, 1987).

1

My rendering of a poem that appears in

Perfume of the Desert: Inspirations from Sufi Wisdom,

edited by A. Harvey and E. Hanut, (Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books, 1999).

My rendering of a poem that appears in

Perfume of the Desert: Inspirations from Sufi Wisdom,

edited by A. Harvey and E. Hanut, (Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books, 1999).

2

From Muhammad Zubayr Siddiqi, “Women Scholars of Hadith,” at

http://www.jannah.org/sisters/womenhadith.html

.

From Muhammad Zubayr Siddiqi, “Women Scholars of Hadith,” at

http://www.jannah.org/sisters/womenhadith.html

.

3

Maulana Muhammad Ali,

The Early Caliphate

(1932; Lahore, Pakistan: The Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha’at Islam, 1983), p. 119.

Maulana Muhammad Ali,

The Early Caliphate

(1932; Lahore, Pakistan: The Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha’at Islam, 1983), p. 119.

4

Ghazali, “On the Etiquettes of Marriage,”

The Revival of the Religious Sciences

book 12 at

http://www.ghazali.org/works/marriage.htm

.

CHAPTER 8Ghazali, “On the Etiquettes of Marriage,”

The Revival of the Religious Sciences

book 12 at

http://www.ghazali.org/works/marriage.htm

.

3

My cousin Farid Ansary quoted this line from a contemporary of Firdausi’s; he couldn’t recall the poet’s name. However, similar (but more extensive) anti-Arab vituperations can be found at the end of Firdausi’s

Shahnama.

CHAPTER 9My cousin Farid Ansary quoted this line from a contemporary of Firdausi’s; he couldn’t recall the poet’s name. However, similar (but more extensive) anti-Arab vituperations can be found at the end of Firdausi’s

Shahnama.

1

Philip Daileader discusses the fragmentation process in medieval Europe in lectures 17-20 of his audio series

The Early Middle Ages

(Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company, 2004). See also the Columbia Encyclopedia, 6

th

edition, entry for “knight.”

Philip Daileader discusses the fragmentation process in medieval Europe in lectures 17-20 of his audio series

The Early Middle Ages

(Chantilly, Virginia: The Teaching Company, 2004). See also the Columbia Encyclopedia, 6

th

edition, entry for “knight.”

3

Ibid., p. 46.

Ibid., p. 46.

4

Quoted by Karen Armstrong in

Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact on Today’s World

(New York: Anchor Books, 2001), pp. 178-179.

Quoted by Karen Armstrong in

Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact on Today’s World

(New York: Anchor Books, 2001), pp. 178-179.

5

Ibid., p. 73.

Ibid., p. 73.

6

Ibid., p. 39.

Ibid., p. 39.

8

Ibid., pp. 64-71.

Ibid., pp. 64-71.

9

Sabbah’s sect resurrected itself as the Nizari Isma’ilis, gained new converts, and rose again, but it morphed into a peaceful movement that is now one of the most progressive sects of Islam, devoted to science and education. Its leader is called the Agha Khan, and the Isma’ilis run the Agha Khan University in Pakistan, one of the brightest centers of learning in today’s Islamic world: everything changes.

Sabbah’s sect resurrected itself as the Nizari Isma’ilis, gained new converts, and rose again, but it morphed into a peaceful movement that is now one of the most progressive sects of Islam, devoted to science and education. Its leader is called the Agha Khan, and the Isma’ilis run the Agha Khan University in Pakistan, one of the brightest centers of learning in today’s Islamic world: everything changes.

10

An account of the sack of Baghdad by Muslim historian Rashid al-Din Fazlullah (1247-1318) appears in

The Middle East and Islamic World Reader

(New York: Grove Press, 2003), p. 49.

An account of the sack of Baghdad by Muslim historian Rashid al-Din Fazlullah (1247-1318) appears in

The Middle East and Islamic World Reader

(New York: Grove Press, 2003), p. 49.

11

The mamluk army was much bigger than Hulagu’s, but the Mongol’s terrible success made them the Goliath in every confrontation.

The mamluk army was much bigger than Hulagu’s, but the Mongol’s terrible success made them the Goliath in every confrontation.

12

Morgan, 146.

CHAPTER 10Morgan, 146.

1

Morgan, pp. 16-18.

Morgan, pp. 16-18.

2

See Akbar Ahmed’s interesting discussion of these differences between the two religions in

Islam Today

, pp. 21-22.

See Akbar Ahmed’s interesting discussion of these differences between the two religions in

Islam Today

, pp. 21-22.

3

Muhammed ibn-al-Husayn al-Sulami,

The Book of Sufi Chivalry: Lessons to a Son of the Moment

(New York: Inner Traditions International, 1983). These stories appear in the forward, pp. 9-14. The ghazis apparently borrowed the story about Omar from a traditional older story about a pre-Islamic king named Nu’man ibn Mundhir.

Muhammed ibn-al-Husayn al-Sulami,

The Book of Sufi Chivalry: Lessons to a Son of the Moment

(New York: Inner Traditions International, 1983). These stories appear in the forward, pp. 9-14. The ghazis apparently borrowed the story about Omar from a traditional older story about a pre-Islamic king named Nu’man ibn Mundhir.

4

Alexandra Marks, writing for the

Christian Science Monitor

on November 25, 1997, said the Coleman Barks’s translation of Rumi,

The Essential Rumi

(San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1995), had sold at that point, a quarter of a million copies worldwide.

Alexandra Marks, writing for the

Christian Science Monitor

on November 25, 1997, said the Coleman Barks’s translation of Rumi,

The Essential Rumi

(San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1995), had sold at that point, a quarter of a million copies worldwide.

5

See Paul Wittek,

The Rise of the Ottoman Empire

(London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1965) pp. 33-51.

See Paul Wittek,

The Rise of the Ottoman Empire

(London: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1965) pp. 33-51.

6

Details of Ottoman society come largely from Stanford Shaw’s

History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), especially pp. 55-65, 113-138, and 150-161.

Details of Ottoman society come largely from Stanford Shaw’s

History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), especially pp. 55-65, 113-138, and 150-161.

7

Zahirud-din Muhammad Babur,

Babur-nama

, translated by Annette S. Beveridge, (1922; Lahor: Sang-e-Meel Publications, reprinted 1987), p. 121.

Zahirud-din Muhammad Babur,

Babur-nama

, translated by Annette S. Beveridge, (1922; Lahor: Sang-e-Meel Publications, reprinted 1987), p. 121.

8

Waldemar Hansen,

The Peacock Throne, The Drama of Mogul India

(New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1972) pp. 113-114, 493-494.

CHAPTER 11Waldemar Hansen,

The Peacock Throne, The Drama of Mogul India

(New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1972) pp. 113-114, 493-494.

1

See C. M. Woolger, “Food and Taste in Europe in the Middle Ages,” pp. 175-177 in

Food: The History of Taste

, edited by Paul Freedman, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

See C. M. Woolger, “Food and Taste in Europe in the Middle Ages,” pp. 175-177 in

Food: The History of Taste

, edited by Paul Freedman, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

Other books

The Summer We All Ran Away by Cassandra Parkin

Ascend (The Vampire Destiny Series Book #4) by Anthony, Alexandra

Lizzie Lynn Lee by Night of the Lions

A Restless Wind by Brandt, Siara

Flight from Berlin by David John

Suicide Italian Style (Crime Made in Italy Book 1) by Pete Pescatore

Dead Right by Brenda Novak

Madonna and Corpse by Jefferson Bass

The Orange Grove by Larry Tremblay

Quid Pro Quo by L.A. Witt