Desert Queen (80 page)

Authors: Janet Wallach

Tags: #Adventure, #Travel, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

When the war with the Turks was over, the Arabs welcomed their British liberators. But the masses of flowers thrown in the streets soon turned to shouts of anger and tears of despair over the occupation. The British were no longer perceived as friends but as another foreign occupier, neither Arab nor Muslim, who invaded their land, evicted their government, and authorized themselves as rulers.

Bell was given the title of Oriental Secretary, a British euphemism for Chief Intelligence Agent. Her job was to sniff and watch the political winds. Bell’s network of informants, which stretched from Damascus to northern Arabia, kept her up-to-date; her friends and acquaintances throughout Mesopotamia included the Shiite leader Sayid Hassan of the al Sadr family, the chief of the Anazeh tribe, Fahad Bey, and the Sunni notable, the Naqib of Baghdad.

Six months after the British victory, the Arab rebellion slowly began. While British officials argued over whether Mesopotamia should be controlled by the Foreign Office or the India Government, Sunni Nationalists whispered about an Arab state and Shiite religious leaders murmured about a holy war against the Christian infidels: in Karbala, tribesmen acting in cahoots with the Turks, spread anti-British propaganda; in Najaf, a group of one hundred Islamicists killed four British political officers and plotted a rebellion with the Euphrates tribes.

By 1919 the Great War had ended, but in Mesopotamia a full insurgency was underway. In Dumair, Arab forces shot the local British political officer, took several others hostage, raided the hospital, the church and the mosques, blew up the oil dump and wounded seventy people, released the prisoners in jail, attacked the British army barracks, and seized control of the town. As the months went on and the tribes took over more territory, merchants were robbed, travelers were subjected to hijackings, and local sheiks were threatened if they cooperated at all with the British authorities.

Assessing the situation, Gertrude Bell changed from believing that the Arabs would accept British rule to insisting that the Arabs be allowed to rule themselves. Forcing them to fit into the British mould, she warned, would only lead to their breaking it. But her colleagues dismissed her ideas and even accused her of being a traitor. In response to the arrogance and intolerance shown by the British military, in the spring of 1920 at the approach of Ramadan, the Shiite holy men openly preached jihad against the infidels, and to the surprise of the British, they were joined by the more secular Sunnis, with whom they did not ordinarily see eye to eye. It was a case of the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Chaos reigned as demonstrations and strikes flared from Basra in the south to Tel Afar in the north. Sunni tribesmen attacked the latter, a city west of Mosul, where they murdered six British political officers. In retaliation, the British machine-gunned the town, evicted every resident, and destroyed every house. Rebels everywhere refused to pay taxes; in Karbala, the holy men were now raging against the occupiers; in Najaf, a small tribe was robbing everyone on the road; in Diwaniyah and Rumaithah, the Arabs cut the railroad lines and stole the British guns. In response the British bombed the towns, fueling more rebellions. Something had to be done. As a concession, the British created an Arab Council of State, a group of mostly Sunni Arab Ministers handpicked and overseen by British advisers and despised by the Shiites.

At home in England, heated debates arose in Parliament and in the press, as politicians and the public argued over the high cost of the war and how quickly the British army should withdraw. To mainitain the 17,000 British and 23,000 Indian troops in Iraq, plus 23,000 more in Palestine, the British government was spending 35.5 million pounds a year. Promising to end the drain on money and men, the new Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill called for a conference in Cairo of his greatest Near East experts; Gertrude Bell, deeply knowledgeable about Iraq and its people, and having worked closely with tribal sheiks and townsmen to draw the borders for a new country of Iraq, arrived at Mena House with a map tucked under her arm.

Her greatest concerns were how to unite the competing tribes and sects and whom to choose to lead them. Her long talks in darkened caves with the clerics of Karbala and Najaf had confirmed her suspicions that the Shiite majority was determined to have an Islamic holy state, but she was resolute that the new country be pro-Western and secular. The solution was to give control to the Sunnis (many of whom had served as administrators for the Turks), but they were in the minority. The only way they could outnumber the Shiites was to include the Kurds—a non-Arab ethnic group that was primarily Sunni Muslim; combined, they would create a Sunni majority.

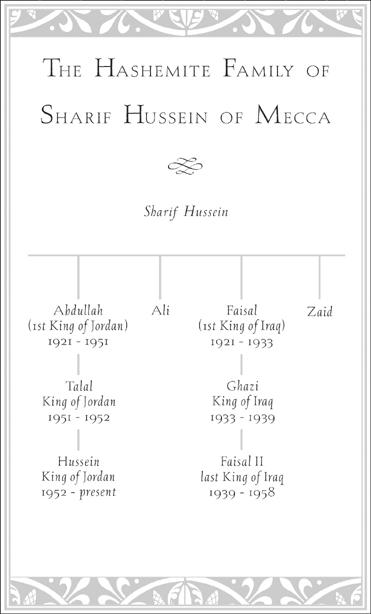

Bell wanted a charismatic leader who had credibility with all Iraqis. She and her colleague T. E. Lawrence agreed the most capable man was the Emir Faisal, the Arab military commander who, bringing together tribes that had fought each other for generations, had rallied them in the revolt against the Turks. In addition, as the son of the Sharif Hussein of Mecca, Faisal was a direct descendant of the Prophet Mohamed and therefore a legitimate leader for both Shiites and Sunnis. Educated in more European Constantinople, he was an eloquent speaker who could captivate his audience. The only downside was that he had never set foot in Iraq.

Gertrude Bell was tasked with turning Faisal into an Iraqi. She greeted him upon his arrival in Baghdad and guided him through the intricacies of Iraq’s history and culture. She brought him to archaeological sites with historic significance and to huge tents in the desert where his oratory won over thousands of tribesmen; she introduced him to notables and townsmen, and he charmed everyone from the Chief Rabbi to the Naqib of Baghdad.

She did everything to ensure that, when a referendum was held, Faisal would be approved: in fact, he won overwhelmingly. The only mistake she made was that Faisal was seen by many as a puppet of the British with a throne stamped “Made in England.” He survived because he was able to balance himself on the political tightrope, shifting this way and that depending on the pro-Arab or pro-British breeze. His skill was duplicated later by his grandnephew King Hussein of Jordan who was as indebted to the United States as Faisal was to Britain; he too knew when to appear as an Arab nationalist and when to appear as an ally with the West.

Faisal appreciated Gertrude Bell’s insights and loyalty and made her his intimate adviser: she helped in everything from designing the flag and writing the constitution to steering the king on his cabinet and setting the palace protocol; in addition, she established the archaeological museum in Baghdad and wrote the Laws of Antiquities. She was determined to make sure that the country kept its proud legacy and protected its greatest pieces; it took the current war in Iraq to destroy much of that.

In the years following World War I, Gertrude Bell was considered the most powerful woman in the British Empire. Newspapers around the world proclaimed her the “Uncrowned Queen of Iraq,” and the “Queen of the Desert.” Her commitment to the newly created country ensured that women had greater rights than under the Turks, along with equal health care and equal education; up until recently, women in Western clothes moved easily through Baghdad and held positions as architects, engineers, archaeologists, teachers, doctors, and lawyers. One can only hope that the same kind of commitment and understanding will help Iraq once again become a pro-Western, secular state composed of and accepted by Shiites, Sunnis, Kurds, and others, united by a charismatic leader wise enough to balance the demands of East and West.

Janet Wallach

March 2005

Glossary

| C ALIPH | Spiritual leader. Considered to be the representative of God on earth. |

| G HAZU | A dangerous and often deadly raid staged by Bedouin in the desert, it can involve as few as a handful or as many as several thousand horsemen. |

| K AFEEYAH | A cloth, of cotton or silk, that is wrapped around the head as protection against the sun and the wind. |

| K HATUN | An important Lady, or the Lady of the Court, who keeps an open eye and ear for the benefit of the State. |

| R AMADAN | A holy month of fasting. Eating is permitted only between sundown and sunrise, and secular festivities are prohibited. |

| S AYID | A descendant of Muhammad through his daughter, Fatima, and her husband, Ali. |

| S HARIF | A descendant of either Hussein or Hassan, grandsons of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and her husband, Ali. The Sharif Hussein was the guardian of the holy sites of Mecca and Medina. |

| S HEIKH | An elder statesman or the head of a village or tribe. One who has either political or religious authority. |

| S HIITE | Member of the Muslim sect that broke off from the Sunni branch of Islam. The political schism developed when the former group wanted to see Ali, a cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad, installed as Caliph and successor to the Prophet. Shiites also follow the doctrine of the Imams, or prayer leaders, who are descendants of the Prophet. |

| S UNNI | The Islamic branch that recognized Abu Bakr as Caliph and legitimate successor to Muhammad. |

| V ILAYET | An Ottoman province (of which there were twenty-four in all). Administered by a governor but actually ruled from the imperial capital of Constantinople. |

| W AHHABI | A sect that follows a strict fundamentalist interpretation of Islamic law. |

Endnotes

PROLOGUE

1

She had been, they seemed to agree …

Morris, James,

Farewell the Trumpets

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978, p. 408.