Desert Queen (2 page)

Authors: Janet Wallach

Tags: #Adventure, #Travel, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

G

ertrude Bell first came to my attention more than twenty years ago when, reading one of her books on the Middle East, I was struck by the courage of this bold Victorian woman. As I was about to travel to that part of the world for the first time, any fears that I had were diminished; indeed, my curiosity was piqued by her descriptions of journeying alone in the early 1900s, surrounded only by Arab men, speaking almost no English, sleeping in tents, riding camel or horse through dangerous regions, risking robbery and even death. I put the book back on the shelf, but the spirit of that intrepid traveler stayed with me.

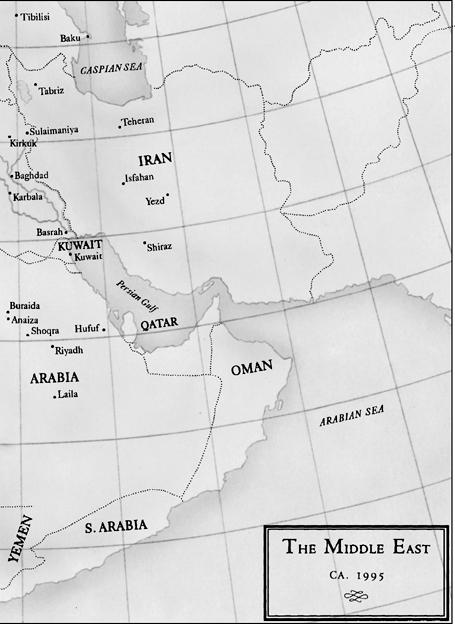

It wasn’t until the Gulf War in 1991 that references to Gertrude Bell popped up in newspapers, books and periodicals. Seeing her name reminded me of her book and my admiration for her. Learning of her importance to the modern Middle East, and in particular her crucial role in Iraq, she seemed to me an ideal subject for a biography. Little did I know just how marvelous a subject she would be.

Gertrude Bell was keenly aware of the importance of her work, often reminding her parents that her letters were a record of history. Thousands of those letters and diary entries are now preserved in the Robinson Library of the University of Newcastle, where I did much of my research. I have tried to be as true to them as possible; where I used conversation and dialogue in

Desert Queen

, the quotes were taken directly from that material or from the letters and memoirs of Gertrude Bell’s family, friends and colleagues. Any changes in spelling, particularly of Arabic words, were done to make the book more unified and the reading a little easier.

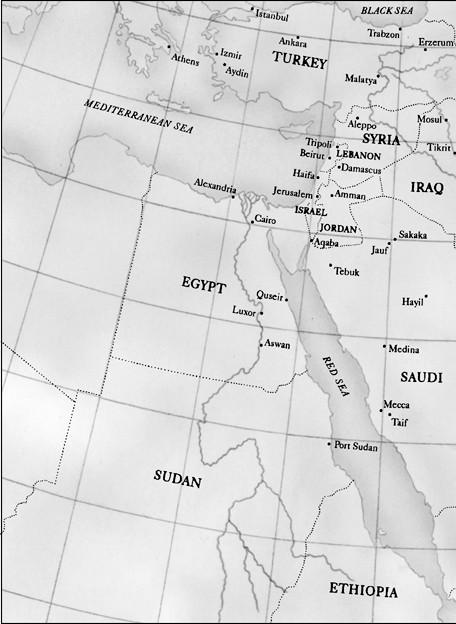

One of the bonuses of writing about Gertrude Bell was the opportunity to travel in her footsteps. I spent time with the Bedouin in the desert and with archaeologists, diplomats, writers and historians in England, Cairo, Damascus, Jerusalem, Amman and, most intriguing of all, Baghdad. I spoke to dozens of people who had heard about her from family and friends and to at least a dozen people who had actually known her themselves (including one who claimed to have been her lover). Some could still recall the authority of her voice, the severeness of her gaze, the exuberance of her dress. Others I spoke with helped me understand the mood of the places, the attitudes of the Arabs, the position of the British, the importance of the tribes, the impact of oil, the role of India. I am grateful to the many people who were so generous with their time, their memories and their knowledge.

I could not have gone to Baghdad without the enormous help of Ambassadors Nizar Hamdoon and Sadoon Zubaidi. Bahnam Abu al Souf, an ebullient archaeologist, and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat, Abdul Razaq Al Hassani, Muayad Sayid Damevji, Esman Gailani, Yousif al Gailani, Amin al Mummayiz and Ali Salah all gave me rare glimpses into Iraqi culture and history.

In Amman, I was fortunate to meet with Prince Raad, Souleiman Moussa, Talal al Patchachi, Abdul Aziz el Dhourie and Qais al Askari, who all had thoughtful insights into the monarchy and the tribes. Marwan Murwasha was, as always, a generous friend. In Cairo, Leila Mansoor helped me find old photographs. In Jerusalem, Val Vester recalled not only “Auntie Gertrude” but Hugh Bell, Florence Bell and Valentine “Domnul” Chirol. Amatzia Baram of Haifa University is an enthusiastic teacher who, undaunted, ploughed through hundreds of pages of manuscript and willingly shared his enormous knowledge.

In London, Roger Hardy of the BBC, Lamya Gailani, Renee Kabir, Nazha Akraui, Salma Sati el Husari and Naha Rahdi were a great help in reconstructing Baghdadi life. My thanks to Caroline Barron for permission to use the papers of her grandfather David Hogarth and at St. Anthony’s College at Oxford, my special thanks to Lady Plowden and to the Trustees of the Trevelyan Family Papers. In Newcastle, Lesley Gordon helped with the Bell papers in the Special Collection of the Robinson Library at the university; Jim Crow steered me through the six thousand photographs taken by Gertrude Bell. Lynn Ritchie gave me excellent advice and Robin Gard kindly served as guide around Newcastle. Jane Hogan helped me in the Palace Green Section of the Durham University Library. At the Oriental Institute at Oxford, Jeremy Johns answered dozens of questions on archaeology and more. Sally Chilton talked fascinatingly about her father, Philip Graves.

In New York my thanks to Selma Rahdi for her help with archaeology and to Linda Fritzinger, a soul mate and scholar on Valentine Chirol. In Boston, Suhair Raad al Mummayiz helped me locate people to interview. In Washington, D.C., Christine Rourke and Betsy Folkins of the Middle East Institute were always willing to search for obscure facts and books; Nancy Wood did marvelous research on mountain climbing. Edmond Ghareeb and Nameer Jawdat were patient readers and teachers. My great thanks to Simon Serfaty, a good friend and wise counselor; Ghida Askari offered good cheer and vivid memories of her grandfather; Tamara Weisberg was always ready to listen; Sue Glaser added her psychologist’s insights on childhood; Amos Perlmutter gave me his ebullient advice on the great British personalities; and Geoffrey Kemp helped me understand the role of India and oil. Christine Helms and Clovis Maksoud both led me to invaluable sources. Tania Hanna was a willing and able research assistant.

Ron Goldfarb and Linda Michaels, my literary agents, were enthusiastic believers from the beginning. My thanks to Jesse Cohen for his patience with endless details. I am indebted to Nan Talese for her encouragement, inspiration and attentive care to this project. Most of all, my thanks to my husband John, whose understanding and love made it possible to write this book.

Janet Wallach

NEW YORK, FEBRUARY 1996

Prologue

S

he was always surrounded by men: rich men, powerful men, diplomats, sheikhs,

*

lovers and mentors. To picture her you had only to envision a red-haired Victorian woman with ramrod posture, piercing green eyes, a long pointed nose and a fragile figure fashionably dressed, and, whether in London, Cairo, Baghdad or the desert, always at the center of a circle of men. So it was only natural that on the drizzly evening of April 4, 1927, less than a year after her death, those who gathered at London’s Royal Geographical Society to pay her tribute were mostly men. Resplendent in white tie and tails, beribboned medals flanking their chests, they marched through the halls recounting their explorations and hers.

“Gertrude Bell,” “Gertrude Bell,” the name flew around the room. She had been, they seemed to agree, the most powerful woman in the British Empire in the years after World War I. Hushed voices called her “the uncrowned queen of Iraq.” They whispered that she was the brains behind Lawrence of Arabia, and a few knowingly ventured that she had drawn the lines in the sand for Winston Churchill.

Some said she had been arrogant, imperious and ruthlessly ambitious, but others knew that flowers and children could melt her heart, and that what she had desperately wanted, more than anything else, was to have been a wife and mother. They had heard she was engaged to be married once, and that later there had been a painful love affair, but they wondered why she had never wed.