Desert Divers (4 page)

Authors: Sven Lindqvist

The first inhabitants of Smara were black and came from the south. Their rock engravings show a Saharan savanna where elephants and giraffes grazed.

In the millennium before our era, they were driven back south by the drought. Those who stayed behind were subjugated by Berber peoples from the north, who rode horses and had weapons made of iron.

The desert deepened all around them. The horse was followed by the camel, which arrived from the east around the year 100 and made possible the regular caravan trade across the desert.

In the year 1000, there was a gang of Saharans who called themselves the ‘Almoravids’. They took over the caravan trade, penetrated northwards and conquered Morocco and Spain. There we got to know them by the name of

Moors

.

In the thirteenth century, all the Saharans who stayed behind in the desert were conquered by a Bedouin tribe, Beni Hassan, emigrating from Yemen. Hassanic Arabic pushed out the Berber language, Znaga. The ruling Arabs accepted tributes from their Znaga vassals who in turn ruled over the black indigenous population: slaves and freed slaves. A council,

djema

, drew up laws and chose a chieftain.

The most famous of these chieftains was Ma Ainin, ‘The Water of the Eyes’. He founded Smara in 1895 as the centre for the Saharan tribes and his headquarters in the struggle against the Europeans.

The main enemy was the French, pressing from the south through Mauritania, from the east through Algeria and soon enough from the north through Morocco. That was why

Vieuchange had to travel in disguise. He belonged to the enemy.

Smara was not colonized until 1934 when the Spaniards, with the help of the French, occupied the town.

Decolonization also came late. The Spaniards were not prepared to hand over power to the Polisario until the mid-1970s.

But the King of Morocco had territorial ambitions. He dreamt of a Greater Morocco that would include parts of Algeria, Mali and Mauritania, and on down to the Senegal river. He maintained that Spanish West Sahara belonged to him for historic reasons.

The matter was referred to the international court at the Hague, which replied that there were indeed legal ties between Morocco and West Sahara, but that these ties did not entail territorial supremacy. The principle of the right to self-determination through the free declaration of the will of the people should, the court decided, be applied without restriction.

What happened next was extremely peculiar. Only in Smara has anything like it ever happened to me.

One evening, I am sitting in the corridor of the Hotel Erraha, talking to a Moroccan greengrocer. He is from Rabat and has been tempted to Smara with subsidies from the government. Here he has a cheap house, earns good money and likes it. And as evidence that there are no problems in the town, he alleges there are no soldiers there.

‘No soldiers, no problems.’

He says this in the Hotel Erraha, which is full of soldiers on leave.

They are sleeping in heaps on the floor of the corridor in front of us.

They have come directly from the fighting at the Wall erected as a defence against the Polisario, sand running off their uniforms, wild-eyed, heads wrapped in cloths and rags. With its music, its lights and occasional women, Smara to them is a paradise compared with the dry dust, the eternal wind and the shadeless heat out there.

Maybe they have no other problems, but they are undeniably soldiers.

Through the hotel window, the greengrocer and I look out over the town. It consists mainly of military installations resembling cartons of eggs with their rows of yellowish-white cupolas. Behind the hotel, army vehicles are lined up in a gigantic military parking lot. In the street below we can see military police walking around in pairs, checking Saharan identity cards. Moroccan conscripts roam in groups along the street, hanging onto each other like teenage girls. A column of army trucks – with their engines running – is ready to depart to the front. The trucks are full of soldiers with closed, sullen, bitter faces.

But the greengrocer maintains they don’t exist.

‘But hang on a minute,’ I say, in appeal. ‘You can’t even go and have a pee without falling over sleeping soldiers. It’s seething with them down there on the street …’

I point out through the window. But that makes no impression on the greengrocer.

‘Further away maybe,’ he says. ‘But here in Smara there are no soldiers, no problems.’

Is he saying what the police have told him to say without bothering to make it plausible? Does he wish, while protecting

himself, to tell me the exact opposite: ‘Many soldiers, many problems’?

I don’t know. All I know is that our conversation ceased once it lost touch with reality.

On October 16, 1975, when the international court decision was delivered, the Moroccan invasion of West Sahara was already planned in detail. Hassan II was unable to back down. He did the same thing as the greengrocer.

He made a great speech in Rabat, explaining that the international court had upheld Morocco’s demands.

To objections that it had done no such thing, he simply declined to answer. Instead he announced a ‘peace march’ to ‘liberate’ West Sahara.

At this threat, the Spaniards suddenly broke off all contact with the Saharans. A curfew was proclaimed. The Spanish Foreign Legion erected barbed wire all around Saharan neighbourhoods. Saharan soldiers were dismissed from the army. Petrol stations stopped selling petrol to Saharans. In a week, twelve thousand Spanish civilians were flown out of the country. Even corpses were evacuated. A thousand dead were dug up out of the local cemeteries and flown to the Canary Isles. The animals in the zoo went with them.

The Spaniards persistently denied ‘rumours’ that they were going to hand over power to the King of Morocco. But in secret they had already done so.

By the time Moroccan troops marched in, the majority of

Smara’s Saharan population had fled across the border into Algeria, 150 miles east. Smara, the main centre of the Saharan liberation movement, became the main base for King Hassan’s war of conquest in the Sahara.

‘Problems? In that case, it’s the goats,’ says the governor.

We are invited to dinner at the governor’s palace. A roast sheep with its ribs exposed like a shipwreck is carried in as we sit there on the sofa, all men, all Moroccans, except me and a Saharan poet. Chicken with orange peel and olives comes next, then sweet rice with almonds, raisins and cinnamon completing the meal.

‘The nomads make their way from the drought in to the water and electricity of the towns,’ says the governor. ‘They settle, motorized herdsmen tending their herds from Landrovers and keeping their families wherever there is a school for their children and healthcare for their old.

‘It is worst for the women. They know nothing except about goats. The woman belongs with goats. Goats are closer to her than her husband, yes, even closer than her children. Her way of bringing up children is out of date, her cooking primitive, and only goats give her a

raison d’être

. So she can’t live without goats. She takes them with her into town. The whole town is full of goats and that creates hygiene problems. It’s simply impossible in modern apartments. I have no hesitation in saying that goats are the greatest social problem we have to contend with at the moment.’

‘And the solution?’

‘I have issued a goat order and appointed one person responsible for goats in each neighbourhood. He sees to it that the neighbourhood is kept free of goats. Each neighbourhood has also been allocated an area outside town, where the goats are allowed. It keeps the women busy – it’s a long walk there to do the milking.’

The Saharan poet Yara Mahjoub is a handsome man of about fifty with brilliant white teeth and a skipper’s wreath of short white hair. He can’t write, not even his name. He carries the whole of his repertoire within him.

‘Is it ten poems? Or a hundred?’ I ask.

‘Oh, many many more! I’d be able to recite them to you all night and all the next day and still have many unspoken.’

‘What are they about?’

‘Give me a subject and I shall sing the praises of it.’

I suggest ‘the judgement of the international court’ and he is immediately prepared.

‘

Sahara reunited with the mother country

the profound connection

between Saharans and the throne –

the evidence now in the hands of the Hague

where it’s been confirmed by the court

so everyone must be convinced

.’

He turns to the assembled company and recites the poem with great bravura, an artist used to performing. Every gesture is part of a stage language, every line in the verse demanding applause.

‘When did you compose your first poem?’

‘It was during the vaccination year, which is also called the “year of the summer rain”. I was eighteen and in love for the first time. This is what it sounded like:

‘

Oh how beautiful it is,

the bridge leading to the hill!

Oh how lovely is the hill’s blue

in her eyes!

’

‘That was in the days of the Spaniards. Did you compose poems in their honour?’

‘I had my camel and my goats. I didn’t need the Spaniards. Father was a goldsmith. So am I. That is my profession. Poetry is my vocation. If I don’t make poems, I fall ill. All real poetry demands inspiration and the love of the King is the greatest source of inspiration. I made this poem during His visit to the USA:

‘

After your journey to the States

and your visit to the Pentagon

your insignificant neighbours scream,

they who are a thorn in your side,

they who rise against Your Majesty,

they scream as if mad with envy.

But they lack food,

yea, they lack soap!

’

One night on his way to Smara, Michel Vieuchange hears far-distant men singing Saharan songs together in the darkness.

As he listens to the resolute gravity in their voices, he thinks there is something peculiar about his own enterprise. What is he really doing there? Is he going to do violence to a secret which ought to remain untouched?

Justified qualms. But he waves them away and struggles on, drunk with fatigue, exhausted, but upright. Elation pours through him despite his torments. He feels chosen, happy, purified by his own flame.

Sometimes his mouth is so dry he has great difficulty pronouncing the single word ‘Ahmed’. He prepares himself for several minutes before attempting it. Only one single word and it seems almost insurmountable.

One of his Saharan companions falls ill and refuses to go on. The little caravan returns to Tiglit. Again Vieuchange is imprisoned in a room with no window, a cloud of flies his only company.

His head is full of one single desire, firm and irrevocable: to complete his journey. He will carry out what he has made up his mind to do. Everything that has been working its way within him since birth is heading towards that goal.

His determination is unyielding. But during the long days of waiting, it changes character.

The thought of Smara no longer gives him any joy. He can no longer find the enthusiasm that has previously borne him along. It has dried out, shrivelled up.

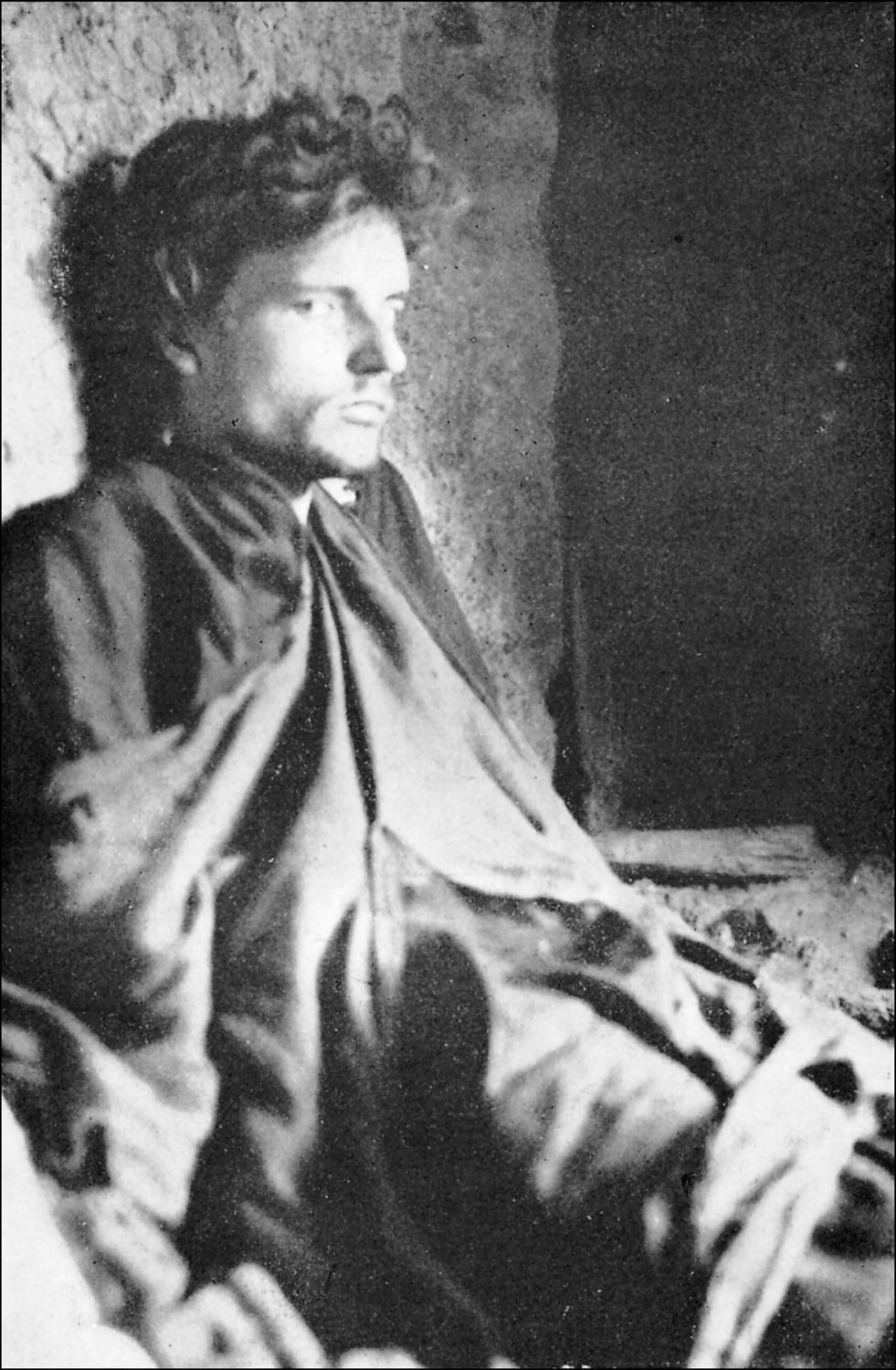

Vieuchange in Tiglit, after his first attempt on Smara.

Decisions are nearly always carried out under different conditions from those under which they are made.

Decisions are made at headquarters. They are carried out in the trenches.

Decisions are made in Paris. They are carried out in the Sahara.

The emotions generated in him by the name ‘Smara’ have disappeared. Remaining is the decision. The will. The intention. When all the humidity has gone, in the end there is nothing left but defiance.

When desire burns out, it is replaced with lies. Vieuchange begins to pretend.

He writes ‘we’ about himself. He pretends he is not alone but travelling with his brother.

He pretends they are on an important assignment through unknown country where no one else has ever seen what they see. In reality, he knows who has been there before him and he has no assignment other than to carry out his own intention.

He pretends they are on their way to a living town. In reality, he knows perfectly well Smara is in ruins and that it was his own countrymen who destroyed it.

These false premises make his enterprise utterly artificial. But this artificiality is documented with extreme authenticity.

Step by step, stone by stone, he describes what it means to do something in the Sahara because he ‘had wanted it, in Paris’.

On November 1, he finally arrives in Smara. He has spent most of the journey hidden in a pannier, curled up in a foetal position, tormented by unbearable cramps, not even seeing the ground.