Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (85 page)

Read Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China Online

Authors: Ezra F. Vogel

Deng wanted to avoid an open split with Chen Yun, but with Hua Guo

feng removed, Deng no longer needed Chen's cooperation in political struggles, and he began to push harder for modernization and economic expansion. When Deng diplomatically raised the question of whether it was useful to have the large disparity between plan rates and actual growth rates that China then had, Chen Yun answered that it was all right for production to surpass planned goals. In fact, in his view it was better to have low goals that were surpassed than to set higher goals: because officials at lower levels were so eager to charge ahead, if higher goals were set, these officials would push beyond what the economy could bear. The result would be a shortage of supplies and inflation, and soon chaos would break out and growth would be stymied.

At the end of 1980, while discussing annual plans for 1981, Chen Yun's ally Yao Yilin had said that the highest possible growth target was 4 percent, though they could strive to achieve 5 percent—and over the long term the most they could grow was 6 percent a year. Hu Yaobang, making every effort to defend Deng's goals, countered by saying that if that were the case, all of their discussions about quadrupling growth by 2000 were meaningless.

3

At the 4th Session of the National People's Congress (NPC) in December 1981, just when the Sixth Five-Year Plan (1981–1985) and the annual plan for 1982 were being considered, disagreements over the speed of growth were so serious that the NPC did not pass an annual budget, nor did it spell out a precise growth target for the Sixth Five-Year Plan.

4

In December 1982, when the Shanghai delegation to an NPC meeting visited Chen Yun at his winter residence in Shanghai, Chen described his view with an analogy used by Huang Kecheng: the economy “is like a bird. You can't hold it in your hand but have to let it fly. But it might fly away, and that is why you need a cage to control it.” To those who wanted a more open economy with faster growth, Chen Yun's “bird cage economics” became the symbol for outdated thinking that stymied market growth. Chen Yun would later explain that what he meant by controls were macroeconomic controls; the cage could be an entire province, the whole country, or in some cases an area even larger than the single nation.

5

This qualification, however, did not stop his critics.

Although Chen Yun's critics sometimes sounded as if he were opposed to all reforms, this was not the case. Chen supported the enterprise reform that Zhao Ziyang had pioneered in Sichuan, which gave businesses increased responsibility for their own profits and losses. He agreed that Beijing should allow enterprises more freedom to buy materials and sell commodities. He

had not opposed rural contracting down to the household, and he supported efforts to decentralize controls over commerce and industry, giving lower-level officials more freedom to push ahead. He was willing to support some price flexibility, so that some of the smaller items then under planning could be taken off the plan and be exchanged on markets. He, too, wanted economic vitality.

6

But he felt responsible for keeping the planning system in good order, for seeing that key industries received the resources they needed, and for ensuring that inflation did not get out of control. On these issues he could be adamant.

The documents issued by the 12th Party Congress (September 1–11, 1982) and by the NPC meetings that followed (November 26–December 10, 1982) reflected the widening gap between Deng and Chen Yun over the targeted speed of growth for China. Most of the documents at the party congress were prepared by the cautious planners. But at Deng's insistence, the congress also took on the goal of quadrupling (

fan liang fan

, literally “doubling twice”) the gross value of industrial and agricultural production by the end of the century. Deng firmly reiterated that it was not good to have a planned rate so much lower than the actual rate.

7

As a disciplined Communist, Chen Yun did not criticize publicly Deng's plan for quadrupling the economy by 2000, but he also did not endorse it. He reiterated that economic construction over the next twenty years should be divided into two decades, the first to lay the foundation with moderate growth, and then a second decade of more rapid growth.

8

The revised Sixth Five-Year Plan (1981–1985), approved at the NPC meeting, represented a victory for the cautious planners. The annual growth target for the five years was set at 4 to 5 percent. Capital construction for the period would be US$23 billion, essentially no increase over the Fifth Five-Year Plan, with an emphasis on energy and transport. And spending on education, science, culture, and health care would increase.

Hu Yaobang believed that one of the ways he could best contribute to modernization was to travel the country giving encouragement to local officials. He listened to their problems and tried to cut through the obstacles to growth. And based on his visits to the countryside, Hu became convinced that local areas had the capacity to grow faster. In response to Chen Yun's argument that China should grow slowly in the 1980s to build a base for more rapid growth in the 1990s, Hu Yaobang said that current leaders should do as much as possible in the 1980s so as not to leave unrealistic goals for those who would lead the economy in the 1990s. In the eyes of Chen

Yun and his cautious planner allies, and even to Zhao Ziyang, Hu Yaobang, in his efforts to be supportive to local officials, was too willing to create exceptions to the rules and not sufficiently concerned about curbing inflation.

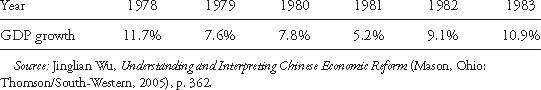

Hu Yaobang's local visits put him on a collision course with Chen Yun. Although the two men had worked well together to reverse verdicts and although Hu remained deferential, Chen Yun was increasingly critical of Hu Yaobang. At a meeting to discuss annual plans on January 12, 1983, Deng again noted that the sixth Five-Year Plan beginning in 1981 still projected an annual growth rate of 3 to 4 percent, but that the actual growth rate was more than twice as high.

Deng asked again if it were appropriate to have such a big gap between the plan and actual performance, and the planners answered that there was no problem.

9

In typical Deng fashion, he then both avoided confrontation and enabled his own strategy to prevail. Without publicly criticizing Chen Yun and the party's decision, he did not restrain local officials from finding ways to expand more rapidly, nor did he keep Hu Yaobang from traveling to the local areas. Once again, Deng had been confronted by a party consensus with which he disagreed and his approach was vintage Deng: “Don't argue, just push ahead.”

Conceptualizing Reform: Zhao Ziyang

Chen Yun agreed in 1980 that Zhao Ziyang should be given a staff to examine the economic issues of the new era, which he realized were different from the period when he had set up the planning system (for more on Zhao, see Key People in the Deng Era, p. 743). When Zhao arrived in Beijing, he accepted the readjustment policies of Chen Yun, and Chen Yun in turn supported Zhao's efforts to allow enterprise managers more autonomy and to contract responsibility for rural production down to the household. In a more general sense, too, Chen Yun appreciated Zhao's efforts to “speak with a Beijing

accent,” to give up his years of thinking like a provincial leader and focus on the national economy as a whole.

Zhao preferred to avoid political struggles; as premier he did not interfere in the work of Chen Yun and the cautious planners in guiding the daily work of economic planning. Instead Zhao and his think tanks, working outside the regular bureaucracy, concentrated on the big issue of how to guide the transition from a relatively closed economy to a more open one. It was natural that after they had been in Beijing for two or three years, Zhao, with help from his staff, had begun to formulate views about new directions for the economy and that Deng would turn to Zhao for guidance. As Deng became impatient with the slow pace of growth under Chen Yun and the cautious planners, he began turning away from Chen Yun and toward Zhao Ziyang and his think tanks for guidance on basic economic policy. Zhao was at the forefront in working with Japanese advisers, as well as the economists and economic officials around the world who had been assembled by the World Bank to conceptualize how China should undertake the transition. To date, no socialist country had successfully—and without serious disruptions—made the shift from a planned economy to a sustained open, market-based economy. Thus when World Bank officials and leading economists from around the world came to China, their most important meeting was with Zhao. Although Zhao did not have formal university training, foreigners were impressed with his knowledge, his intellectual curiosity, his ability to grasp new ideas, and his analytic abilities.

10

When he visited Beijing in 1988, the famous American economist Milton Friedman expected a half-hour session with Zhao, but the discussion with Zhao, Friedman, and an interpreter alone lasted two full hours. Friedman said about Zhao, “He displayed a sophisticated understanding of the economic situation and of how the market operated.” Friedman described the meeting as “fascinating.”

11

One of Zhao's think tanks that played a key role in rural reforms was the small (thirty member) China Rural Development Research Group. It had its origins in a discussion group of bright university graduates who had a deep knowledge of the situation in the countryside from their years “rusticating” there during the Cultural Revolution. In November 1981, it became an independent institute under the Agricultural Economics Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

12

Later it would be incorporated into the Research Center for Rural Development under the State Council, where it did the staff work in the policy formulation for contracting down to the household

and later the basic drafting of the yearly Document No. 1 of the Central Committee, which adjusted agricultural policy.

13

Another think tank was the System Reform Commission

(Tizhi gaige weiyuanhui)

, which was established to consider fundamental system reforms. Because it could recommend bureaucratic reorganization, some bureaucrats were nervous about what it might propose. It began as a small group under the Chinese Academy of Sciences studying system reform; in 1981, it was reorganized as the System Reform Office and placed under Zhao; and in March 1982, it was renamed the System Reform Commission and raised to ministerial level. By 1984, under the direction of Premier Zhao Ziyang, it was employing around one hundred officials.

14

Bao Tong, a loyal and studious official, originally assigned to Zhao by the Organization Department of the party, began to function in effect as Zhao's chief of staff.

Those who worked under Zhao at the think tanks had great respect and admiration for him. They appreciated his lack of pretense, his informal style, his openness to ideas from people of any rank, and his skill in moving from ideas to practical policies that would move the country forward.

Learning from Abroad

On June 23, 1978, after listening to a report by the Ministry of Education on plans to send students abroad, Deng said he wanted to increase the number of students going abroad to the tens of thousands. Deng believed that for China to modernize quickly, it had to learn about and adapt ideas that were working overseas. The Soviets, who feared a “brain drain,” were reluctant to let their promising scholars and students go abroad. Mao had closed the doors with the West. Even Chiang Kai-shek had worried about rapidly losing some of his smartest young people. But Deng never worried about a brain drain. As a result, no developing country other than Japan and South Korea could compare with Deng's China in the scope and depth of its efforts to learn the secrets of modernization from advanced countries. And China, with its huge population, quickly surpassed those two countries in the scale of its learning from abroad.

Deng sent officials abroad on study tours, he invited in foreign specialists, he set up centers to study foreign developments, he encouraged efforts to translate foreign information into Chinese—all on a huge scale. Unlike Japanese and South Korean leaders, who worried that their domestic companies

might be overwhelmed by foreign competition, Deng encouraged foreign companies to set up modern factories in China to help train Chinese managers and workers. He made good use of the ethnic Chinese who lived abroad and could assist in understanding developments overseas. But above all he encouraged young people to go abroad to study. During the three decades, from 1978 to 2007, more than a million Chinese students studied abroad, and by the end of those three decades about a quarter of them had already returned to China.

15

In learning about foreign economic developments, Deng allowed Zhao to meet the economists; he preferred to talk with scientists and successful business leaders like Y. K. Pao, Matsushita Konosuke, and David Rockefeller, to collect their ideas on how China could progress. He also met foreigners involved in national economic planning, like Okita Saburo and Shimok be Atsushi of Japan. Beginning in early 1979, every few days a report written by senior Chinese scholars was published outlining key foreign developments that were important for the Chinese economy: these were known as

be Atsushi of Japan. Beginning in early 1979, every few days a report written by senior Chinese scholars was published outlining key foreign developments that were important for the Chinese economy: these were known as

Jingji cankao ziliao

(“economic reference materials”). When delegations went abroad they wrote reports about what they learned, and the reports were then made available to Chinese leaders.