Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (664 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

“Hurrah, Sadie! Hurrah, my own darling Sadie!” she was shrieking. “We are saved, my girl, we are saved after all.”

“By George, so we are!” cried the Colonel, and they all shouted in an ecstasy together.

But Sadie had learned to think more about others during those terrible days of schooling. Her arms were round Mrs. Belmont, and her cheek against hers.

“You dear, sweet angel,” she cried, “how can we have the heart to be glad when you — when you — —”

“But I don’t believe it is so,” cried the brave Irishwoman. “No, I’ll never believe it until I see John’s body lying before me. And when I see that, I don’t want to live to see anything more.”

The last Dervish had clattered down the khor, and now above them on either cliff they could see the Egyptians — tall, thin, square-shouldered figures, looking, when outlined against the blue sky, wonderfully like the warriors in the ancient bas-reliefs. Their camels were in the background, and they were hurrying to join them. At the same time others began to ride down from the farther end of the ravine, their dark faces flushed and their eyes shining with the excitement of victory and pursuit. A very small Englishman, with a straw-coloured moustache and a weary manner, was riding at the head of them. He halted his camel beside the fugitives and saluted the ladies. He wore brown boots and brown belts with steel buckles, which looked trim and workmanlike against his kharki uniform.

“Had ‘em that time — had ‘em proper!” said he. “Very glad to have been of any assistance, I’m Shaw. Hope you’re none the worse for it all. What I mean, it’s rather rough work for ladies.”

“You’re from Haifa, I suppose?” asked the Colonel.

“No, we’re from the other show. We’re the Sarras crowd, you know. We met in the desert, and we headed ‘em off, and the other Johnnies headed them behind. We’ve got ‘em on toast, I tell you. Get up on that rock and you’ll see things happen. It’s going to be a knockout in one round this time.”

“We left some of our people at the wells. We are very uneasy about them,” said the Colonel. “I suppose you have not heard anything of them?”

The young officer looked serious and shook his head. “Bad job that!” said he. “They’re a poisonous crowd when you put ‘em in a corner. What I mean, we never expected to see you alive; and we’re very glad to pull any of you out of the fire. The most we hoped was that we might revenge you.”

“Any other Englishman with you?” “Archer is with the flanking party. He’ll have to come past, for I don’t think there is any other way down. We’ve got one of your chaps up there — a funny old bird with a red topknot. See you later, I hope! Good day, ladies!” He touched his helmet, tapped his camel, and trotted on after his men.

“We can’t do better than stay where we are until they are all past,” said the Colonel, for it was evident now that the men from above would have to come round. In a broken single file they went past, black men and brown, Soudanese and fellaheen, but all of the best, for the Camel Corps is the

corps d’elite

of the Egyptian army. Each had a brown bandolier over his chest and his rifle held across his thigh. A large man with a drooping black moustache and a pair of binoculars in his hand was riding at the side of them.

“Hulloa, Archer!” croaked the Colonel.

The officer looked at him with the vacant, unresponsive eye of a complete stranger.

“I’m Cochrane, you know! We travelled up together.”

“Excuse me, sir, but you have the advantage of me,” said the officer. “I knew a Colonel Cochrane, but you are not the man. He was three inches taller than you, with black hair and — —”

“That’s all right,” cried the Colonel, testily. “You try a few days with the Dervishes, and see if your friends will recognise you!”

“Good God, Cochrane, is it really you? I could not have believed it. Great Scott, what you must have been through! I’ve heard before of fellows going grey in a night, but, by Jove — —”

“Quite so,” said the Colonel, flushing. “Allow me to hint to you, Archer, that if you could get some food and drink for these ladies, instead of discussing my personal appearance, it would be much more practical.”

“That’s all right,” said Captain Archer.

“Your friend Stuart knows that you are here, and he is bringing some stuff round for you. Poor fare, ladies, but the best we have! You’re an old soldier, Cochrane. Get up on the rocks presently, and you’ll see a lovely sight. No time to stop, for we shall be in action again in five minutes. Anything I can do before I go?”

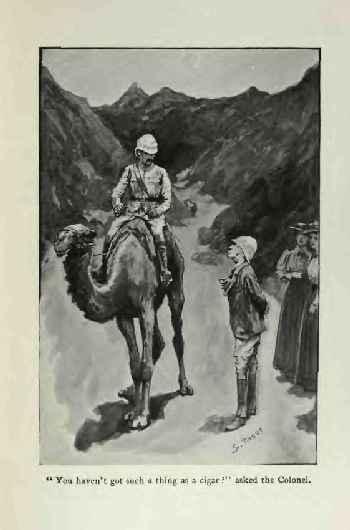

“You haven’t got such a thing as a cigar?” asked the Colonel, wistfully.

Archer drew a thick satisfying partaga from his case and handed it down, with half-a-dozen wax vestas. Then he cantered after his men, and the old soldier leaned back against the rock and drew in the fragrant smoke. It was then that his jangled nerves knew the full virtue of tobacco, the gentle anodyne which stays the failing strength and soothes the worrying brain. He watched the dim, blue reek swirling up from him, and he felt the pleasant, aromatic bite upon his palate, while a restful languor crept over his weary and harassed body. The three ladies sat together upon a flat rock.

“Good land, what a sight you are, Sadie!” cried Miss Adams, suddenly, and it was the first reappearance of her old self. “What

would

your mother say if she saw you? Why, sakes alive, your hair is full of straw and your frock clean crazy!”

“I guess we all want some setting to right,” said Sadie, in a voice which was much more subdued than that of the Sadie of old. “Mrs. Belmont, you look just too perfectly sweet anyhow, but if you’ll allow me, I’ll fix your dress for you.”

But Mrs. Belmont’s eyes were far away, and she shook her head sadly as she gently put the girl’s hands aside.

“I do not care how I look. I cannot think of it,” said she; “could

you

, if you had left the man you love behind you, as I have mine?”

“I’m begin — beginning to think I have,” sobbed poor Sadie, and buried her hot face in Mrs. Belmont’s motherly bosom.

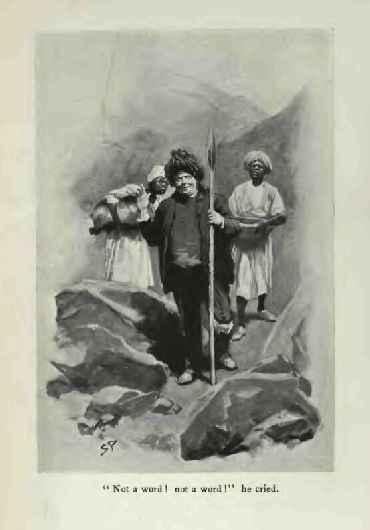

The Camel Corps had all passed onwards down the khor in pursuit of the retreating Dervishes, and for a few minutes the escaped prisoners had been left alone. But now there came a cheery voice calling upon them, and a red turban bobbed about among the rocks, with the large white face of the Nonconformist minister smiling from beneath it. He had a thick lance with which to support his injured leg, and this murderous crutch combined with his peaceful appearance to give him a most incongruous aspect, — as of a sheep which has suddenly developed claws. Behind him were two negroes with a basket and a water-skin.

“Not a word! Not a word!” he cried, as he stumped up to them. “I know exactly how you feel. I’ve been there myself. Bring the water, Ali! Only half a cup, Miss Adams; you shall have some more presently. Now your turn, Mrs. Belmont! Dear me, dear me, you poor souls, how my heart does bleed for you! There’s bread and meat in the basket, but you must be very moderate at first.” He chuckled with joy, and slapped his fat hands together as he watched them.

“But the others?” he asked, his face turning grave again.

The Colonel shook his head. “We left them behind at the wells. I fear that it is all over with them.”

“Tut, tut!” cried the clergyman, in a boisterous voice, which could not cover the despondency of his expression; “you thought, no doubt, that it was all over with me, but here I am in spite of it. Never lose heart, Mrs. Belmont. Your husband’s position could not possibly be as hopeless as mine was.”

“When I saw you standing on that rock up yonder, I put it down to delirium,” said the Colonel. “If the ladies had not seen you, I should never have ventured to believe it.”

“I am afraid that I behaved very badly. Captain Archer says that I nearly spoiled all their plans, and that I deserved to be tried by a drumhead court-trial and shot. The fact is that, when I heard the Arabs beneath me, I forgot myself in my anxiety to know if any of you were left.”

“I wonder that you were not shot without any drumhead court-martial,” said the Colonel. “But how in the world did you get here?”

“The Haifa people were close upon our track at the time when I was abandoned, and they picked me up in the desert. I must have been delirious, I suppose, for they tell me that they heard my voice, singing hymns, a long way off, and it was that, under the providence of God, which brought them to me. They had a camel ambulance, and I was quite myself again by next day. I came with the Sarras people after we met them, because they have the doctor with them. My wound is nothing, and he says that a man of my habit will be the better for the loss of blood. And now, my friends,” — his big, brown eyes lost their twinkle, and became very solemn and reverent,—”we have all been upon the very confines of death, and our dear companions may be so at this instant. The same power which saved us may save them, and let us pray together that it may be so, always remembering that if, in spite of our prayers, it should

not

be so, then that also must be accepted as the best and wisest thing.”

So they knelt together among the black rocks, and prayed as some of them had never prayed before. It was very well to discuss prayer and treat it lightly and philosophically upon the deck of the

Korosko

. It was easy to feel strong and self-confident in the comfortable deck-chair, with the slippered Arab handing round the coffee and liqueurs. But they had been swept out of that placid stream of existence, and dashed against the horrible, jagged facts of life. Battered and shaken, they must have something to cling to. A blind, inexorable destiny was too horrible a belief. A chastening power, acting intelligently and for a purpose, — a living, working power, tearing them out of their grooves, breaking down their small sectarian ways, forcing them into the better path, — that was what they had learned to realise during these days of horror. Great hands had closed suddenly upon them and had moulded them into new shapes, and fitted them for new uses. Could such a power be deflected by any human supplication? It was that or nothing, — the last court of appeal, left open to injured humanity. And so they all prayed, as lover loves, or a poet writes, from the very inside of their souls, and they rose with that singular, illogical feeling of inward peace and satisfaction which prayer only can give.

“Hush!” said Cochrane. “Listen!” The sound of a volley came crackling up the narrow khor, and then another and another. The Colonel was fidgeting about like an old horse which hears the bugle of the hunt and the yapping of the pack. “Where can we see what is going on?” “Come this way! This way, if you please! There is a path up to the top. If the ladies will come after me, they will be spared the sight of anything painful.”

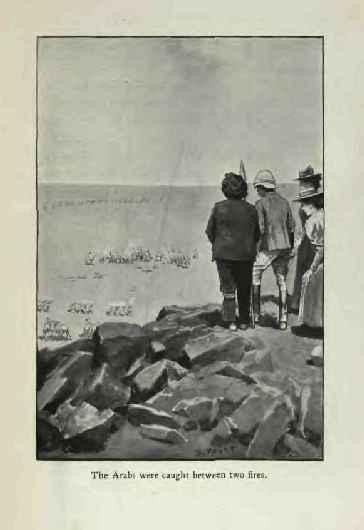

The clergyman led them along the side to avoid the bodies which were littered thickly down the bottom of the khor. It was hard walking over the shingly, slaggy stones, but they made their way to the summit at last. Beneath them lay the vast expanse of the rolling desert, and in the foreground such a scene as none of them are ever likely to forget. In that perfectly dry and clear light, with the unvarying brown tint of the hard desert as a background, every detail stood out as clearly as if these were toy figures arranged upon a table within hand’s touch of them.

The Dervishes — or what was left of them — were riding slowly some little distance out in a confused crowd, their patchwork jibbehs and red turbans swaying with the motion of their camels. They did not present the appearance of men who were defeated, for their movements were very deliberate, but they looked about them and changed their formation as if they were uncertain what their tactics ought to be. It was no wonder that they were puzzled, for upon their spent camels their situation was as hopeless as could be conceived. The Sarras men had all emerged from the khor, and had dismounted, the beasts being held in groups of four, while the riflemen knelt in a long line with a woolly, curling fringe of smoke, sending volley after volley at the Arabs, who shot back in a desultory fashion from the backs of their camels. But it was not upon the sullen group of Dervishes, nor yet upon the long line of kneeling riflemen, that the eyes of the spectators were fixed. Far out upon the desert, three squadrons of the Haifa Camel Corps were coming up in a dense close column, which wheeled beautifully into a widespread semicircle as it approached. The Arabs were caught between two fires.

“By Jove!” cried the Colonel. “See that!”

The camels of the Dervishes had all knelt down simultaneously, and the men had sprung from their backs. In front of them was a tall, stately figure, who could only be the Emir Wad Ibrahim. They saw him kneel for an instant in prayer. Then he rose, and taking something from his saddle he placed it very deliberately upon the sand and stood upon it.

“Good man!” cried the Colonel. “He is standing upon his sheepskin.”

“What do you mean by that?” asked Stuart.

“Every Arab has a sheepskin upon his saddle. When he recognises that his position is perfectly hopeless, and yet is determined to fight to the death, he takes his sheepskin off and stands upon it until he dies. See, they are all upon their sheepskins. They will neither give nor take quarter now.”

The drama beneath them was rapidly approaching its climax. The Haifa Corps was well up, and a ring of smoke and flame surrounded the clump of kneeling Dervishes, who answered it as best they could. Many of them were already down, but the rest loaded and fired with the unflinching courage which has always made them worthy antagonists. A dozen kharki-dressed figures upon the sand showed that it was no bloodless victory for the Egyptians. But now there was a stirring bugle-call from the Sarras men, and another answered it from the Haifa Corps. Their camels were down also, and the men had formed up into a single long curved line. One last volley and they were charging inwards with the wild inspiriting yell which the blacks had brought with them from their central African wilds. For a minute there was a mad vortex of rushing figures, rifle-butts rising and falling, spearheads gleaming and darting among the rolling dust cloud. Then the bugle rang out once more, the Egyptians fell back and formed up with the quick precision of highly disciplined troops, and there in the centre, each upon his sheepskin, lay the gallant barbarian and his raiders. The nineteenth century had been revenged upon the seventh.

The three women had stared horror-stricken and yet fascinated at the stirring scene before them. Now Sadie and her aunt were sobbing together. The Colonel had turned to them with some cheering words when his eyes fell upon the face of Mrs. Belmont. It was as white and set as if it were carved from ivory, and her large grey eyes were fixed as if she were in a trance.

“Good Heavens, Mrs. Belmont, what

is

the matter?” he cried.

For answer she pointed out over the desert. Far away, miles on the other side of the scene of the fight, a small body of men were riding towards them.

“By Jove, yes; there’s some one there. Who can it be?”

They were all straining their eyes, but the distance was so great that they could only be sure that they were camel-men and about a dozen in number.

“It’s those devils who were left behind in the palm grove,” said Cochrane. “There’s no one else it can be. One consolation, they can’t get away again. They’ve walked right into the lion’s mouth.”

But Mrs. Belmont was still gazing with the same fixed intensity and the same ivory face. Now, with a wild shriek of joy, she threw her two hands into the air. “It’s they!” she screamed. “They are saved! It’s they, Colonel, it’s they! O Miss Adams, Miss Adams, it is they!” She capered about on the top of the hill with wild eyes like an excited child.

Her companions would not believe her, for they could see nothing, but there are moments when our mortal senses are more acute than those who have never put their whole heart and soul into them can ever realise. Mrs. Belmont had already run down the rocky path, on the way to her camel, before they could distinguish that which had long before carried its glad message to her. In the van of the approaching party, three white dots shimmered in the sun, and they could only come from the three European hats. The riders were travelling swiftly, and by the time their comrades had started to meet them they could plainly see that it was indeed Belmont, Fardet, and Stephens, with the dragoman Mansoor, and the wounded Soudanese rifleman. As they came together they saw that their escort consisted of Tippy Tilly and the other old Egyptian soldiers. Belmont rushed onwards to meet his wife, but Fardet stopped to grasp the Colonel’s hand.

“

Vive la France! Vivent les Anglais!

” he was yelling. “

Tout va bien, n’est ce pas

, Colonel?

Ah,

canaille! Vivent les croix et les Chrétiens!

” He was incoherent in his delight.

The Colonel, too, was as enthusiastic as his Anglo-Saxon standard would permit. He could not gesticulate, but he laughed in the nervous, crackling way which was his top-note of emotion.

“My dear boy, I am deuced glad to see you all again. I gave you up for lost. Never was as pleased at anything in my life! How did you get away?”

“It was all your doing.”

“Mine?”