Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1399 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

On July 27 the division was relieved by the extension of the flanks of its two neighbours, but it was at once fitted into the line again, filling a battle-front of

The barrage was not as deadly as usual on account of the pressure of time which had hampered the preparation and registration. The slopes were long and open, swept by the deadly machine-guns. It was all odds against the attack. The 103rd Brigade got to the outskirts of Beugneux, but was held up by the murderous fire from an adjacent mill. The 101st surmounted the ridge between Grand Rozoy and Beugneux, but could get no farther, for it was all open ground to the north.

In the early afternoon the 102nd Brigade advanced from the wood in which it lay with the intention of helping the 101st to storm Beugneux, but as it came forward it met the 101st falling back before a strong counter-attack. This movement was checked by the new-comers and the line was sustained upon the ridge.

The net result of an arduous day was that the division was still short of the coveted road, but that it had won about

On August 1 the attack was renewed under a very heavy and efficient barrage, which helped the infantry so much that within two hours all objectives had been won. Beugneux fell after the hill which commanded it had been stormed by the 8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in a very gallant advance. Colonel Barbow fell while leading his men to victory. On the left the French Twenty-fifth Division had been held up by the deadly fire from a knoll, but Major Atkinson of the 2nd North Lancashires realised the situation and diverted his reserve company to storm the obstacle, enabling the French right to get forward. It was planned that two British battalions should push on beyond their objectives in order to cover the flanks of a further French advance. One of these, the 4th Cheshires, carried out its part to perfection in spite of heavy losses, which included Colonel Swindells, its commander. The 1st Herefords, however, whose rôle was to cover the left of the Sixty-eighth French Division, was unable to do so, as that division was itself held up. That night the enemy was in full retreat all along this line, and falling back upon the River Vesle. On August 3 the Thirty-fourth Division was returned to the area of the Second British Army, having done a fine spell of service which brought the warmest compliments from the French commanders, not only to the infantry, but to General Walthall’s guns (152nd and 160th Brigades) as well as Colonel Dobson’s 207th, 208th, and 209th Field Companies.

The northward advance of the French, Americans, and British was slow up to the end of July, but became accelerated in the first week of August, Soissons falling to the French on August 2, and the Germans being driven to the line of the Vesle, when they held on very tenaciously for a time, their rearguards showing their usual high soldierly qualities. The Americans had a particularly hard struggle, being faced by some of the elite of the German Army, including the 4th Prussian Guards, but winning their way steadily forward in spite of many strong counter-attacks. The situation upon the Vesle and the Aisne seemed for the moment to have reached an equilibrium, when Marshal Foch called Marshal Haig to his assistance and a new attack was launched in which British troops were once more employed on the grand scale. Their great march had started which was to end only at the bank of the Rhine.

Before embarking upon this narrative, it would be well to prevent the necessity of interrupting it by casting a glance at those general events connected with the world war which occurred during this period, which reacted upon the Western front. It has already been shortly stated that the Austrian Army had been held in their attempt to cross the Piave in mid June, and by the end of the month had been driven over the river by the Italians, aided by a strong British and French contingent. The final losses of the Austrians in this heavy defeat were not less than 20,000 prisoners with many guns. From this time until the final Austrian débâcle there was no severe fighting upon this front. In the Salonican campaign the Greek Army was becoming more and more a factor to be reckoned with, and the deposition of the treacherous Constantine, with the return to power of Venizelos, consolidated the position of the Allies. There was no decided movement, however, upon this front until later in the year. In Palestine and in Mesopotamia the British forces were also quiescent, Allenby covering the northern approaches of Jerusalem, and preparing for his last splendid and annihilating advance, while Marshall remained in a similar position to the north of Bagdad. A small and very spirited expedition sent out by the latter will no doubt have a history of its own, for it was adventurous to a degree which was almost quixotic, and yet justified itself by its results. This was the advance of a handful of men over

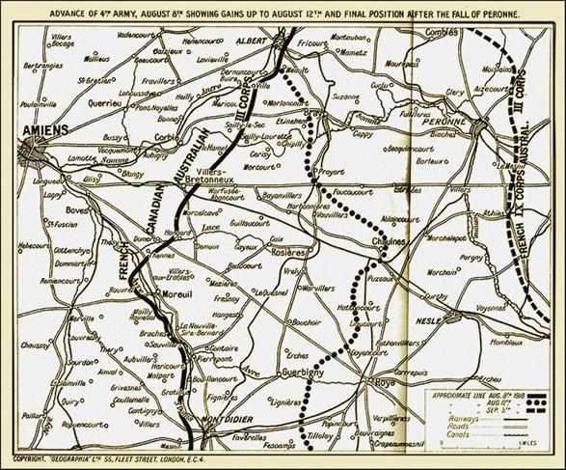

Advance of Fourth Army, August 8, showing Gains up to August 12,

and Final Position after the Fall of Peronne

II. ATTACK OF RAWLINSON’S FOURTH ARMY

The Battle of Amiens, August 8–22

Great British victory — Advance of the Canadians — Of the Australians — Of the Third Corps — Hard struggle at Chipilly — American assistance — Continuance of the operations — Great importance of the battle

IN the tremendous and decisive operations which we are now about to examine, it is very necessary to have some fixed scheme in the method of description s lest the reader be inextricably lost in the long line of advancing corps and armies. A chapter will be devoted, therefore, to the attack made by Rawlinson’s Fourth Army whilst it was operating alone from August 8 to August 22. At that date Byng’s Third Army joined in the fray, and subsequently, on August 28, Horne’s First Army came into action. For the present, however, we can devote ourselves whole-heartedly to the record of Rawlinson’s Army, all the rest being inactive. When the others come in, that is, after August

Before describing the great battle some reference should be made to the action of Le Hamel fought on July 4, noticeable as having been the first Allied offensive since the early spring. Its complete success, after the long series of troubles which had plunged all friends of freedom into gloom, made it more important than the numbers engaged or the gain of ground would indicate. It was carried out by the Australian Corps, acting as part of the Fourth Army, and is noticeable because a unit from the Thirty-third American Division took part in the operations. Le Hamel was taken and the Vaire Wood to the immediate south of the Somme. The gain of ground was about a mile in depth on a front of several miles, and the advance was so swift that a considerable number of prisoners,

The front of the new and most important attack, which began in the early morning of August 8, was fifteen miles in length, and extended from near Morlancourt in the north to Braches upon the Avre River to the south. The right of the attack from Hangard onwards was formed by General Debeney’s First French Army, while General Rawlinson’s Fourth Army formed the left, the British position being roughly three-fourths of the whole. The entire battle was under the command of Marshal Haig.

The preparations had been made with the skill which the British Command has so often shown in such operations, so that the Germans were swept off their feet by an attack which came upon them as a complete surprise. It was half-past four on a misty morning when the enemy’s advanced line heard the sudden crash of the gun-fire, and a moment later saw the monstrous forms of the tanks looming up through the grey light of dawn. Behind the tanks and almost in touch of them came the grim war-worn infantry. Everything went down before that united rush. The battle was won as soon as begun. The only question was how great the success would be.

Taking a bird’s-eye view of the advance, before examining the operations more closely, one may say that the Canadian Corps, now under a Canadian commander, General Currie, was on the extreme right of the British fine, in touch with the French. Next to them, in the Morlancourt district, where they had never ceased for the last four months to improve their position and to elbow the invaders away from Amiens, were the indomitable and tireless Australians under General Monash. On their left, just south of Albert, was Butler’s Third Corps, burning to avenge itself for the hustling which it had endured during that perilous and heroic week in March. These were the three units concerned in the new advance.

The opening barrage, though only a few minutes in length, was of a shattering severity, and was directed against very different defences from those which had defied the Army two years before upon the Somme. Everything flattened out before it, and even the German guns seemed to have been overwhelmed, for their reply was slow and ineffective. Only the machine-guns remained noxious, but the tanks rolled them down. Nowhere at first was there any check or delay. The French on the right of the line had done equally well, and by midday were storming forward upon the north bank of the Avre, their victory being the more difficult and honourable because the river prevented the use of tanks at the first attack.

The Canadians were on the top of their form that day, and their magnificent condition gave promise of the splendid work which they were to do from that hour until almost the last day of the war. They were probably the most powerful and efficient corps at that moment in the whole Army, for they had lain in front of Lens with few losses, while nearly every other corps had been desperately engaged and sustained heavy casualties, hastily made good by recruits. They had also kept their brigades up to a four battalion standard, and their divisions had that advantage of permanence denied to all British corps. When to these favouring points are added the great hardihood and valour of the men, proved in so many battles, it is probable that in the whole world no finer body could on that day have been let loose behind a barrage. They were weary from long marches before the battle began, but none the less their great spirit rose high above all physical weakness as they pushed forward against the German line.

They were faced at the outset by a problem which might well have taxed the brains of any staff and the valour of any soldiers. This was the crossing of the River Luce, which was covered upon the farther bank by several scattered woods, ideal haunts of machine-guns. So difficult was this operation that the French to the south had to pause for an hour after the capture of the front German line, to give time for it to be carried out. At the end of that period the very complex operation had been carried through, and the whole Allied front was ready to advance. The Canadians had three divisions in the line, the Third (Lipsett) next to the French, the First (Macdonell) in the middle, and the Second (Benstall) on the left. The 2nd and 3rd British Cavalry Brigades with the Fourth Canadian Infantry Division (Watson) were in reserve. There was also a mobile force, called the Canadian Independent Force, which was kept ready to take advantage of any opening. This consisted of the 1st and 2nd Canadian Motor Machine-gun Brigades, with the Corps Cyclists, and some movable trench mortars on lorries.

The width of the Canadian attack was some

We shall now turn to the advance of Monash’s Australians in the centre of the British line. Fate owed Monash a great victory in this sector, for, during months of quiet but ceaseless work, he had been improving his position as the keen runner ensures his foothold and crouches his body while he awaits the crack of the pistol.

For once Fate paid its debts, and with such a corps under his hand it would have been strange had it not been so. All those advantages already described in the case of the Canadians applied equally to the Australians, and if the former outlasted the others, it must be remembered that the Australians had been in the line for four months before the fighting began — months which included the severe action of Villers-Bretonneux. They were a grand corps, and they did grand work for the Empire — work which we can never forget so long as our common history endures.

The order of battle of the Australian Corps on August 8 was that the Second Division (Smyth) was on the right in touch with the Canadians, while the Third Division (Gillibrand) was on the left in touch with the Fifty-eighth British Division, the Somme being the dividing line between them. Behind the Second Australians was the Fifth (Hobbs), and behind; the Third the Fourth (Maclagan), with orders in each case to leapfrog over their leaders when the first objectives were carried. The First Division (Glasgow) was in the immediate rear. Thus at least 50,000 glorious infantry marched to battle under the Southern Cross Union Jack upon this most historic day — a day which, as Ludendorfi has since confessed, gave the first fatal shock to the military power of Germany.

All depended upon surprise, and the crouching troops waited most impatiently for the zero hour, expecting every instant to hear the crash of the enemy’s guns and the whine of the shrapnel above the assembly trenches. Every precaution had been taken the day before, the roads had been deserted by all traffic, and aeroplanes had flown low during the night, so that their droning might cover the noise of the assembling tanks. Some misgiving was caused by the fact that a sergeant who knew all about it had been captured several days before. By a curious chance the minutes of his cross-examination by the German intelligence officer were captured during the battle. He had faced his ordeal like a Spartan, and had said no word. It is not often that the success of a world-shaking battle depends upon the nerve and the tongue of a single soldier.

Zero hour arrived without a sign, and in an instant barrage tanks, and infantry all burst forth together, though the morning mist was so thick that one could only see twenty or thirty yards. Everywhere the enemy front posts went down with hardly a struggle. It was an absolute surprise. Now and then, as the long, loose lines of men pushed through the mist, there would come the flash of a field-piece, or the sudden burst of a machine-gun from their front; but in an instant, with the coolness born of long practice, the men would run crouching forward, and then quickly-close in from every side, shooting or bayoneting the gun crew. Everything went splendidly from the first, and the tanks did excellent service, especially in the capture of Warfusee.

The task of the two relieving divisions, the Fourth on the left and the Fifth on the right, was rather more difficult, as the Germans had begun to rally and the fog to lift. The Fourth Australians on the south bank of the Somme were especially troubled, as it soon became evident that the British attack on the north bank had been held up, with the result that the German guns on Chipilly Spur were all free to fire across from their high position upon the Australians in the plain to the south. Tank after tank and gun after gun were knocked out by direct hits, but the infantry was not to be stopped and continued to skirmish forward as best they might under so deadly a fire, finishing by the capture of Cerisy and of Morcourt. The Fifth Division on the right, with the 8th and 15th Brigades in front, made an equally fine advance, covering a good stretch of ground.

Having considered the Canadians and the Australians, we turn now to the Third Corps on the north of the line. They were extended from Morlancourt to the north bank of the Somme, which is a broad canalised river over all this portion of its course. On the right was the Fifty-eighth London Division (Ramsay), with Lee’s Eighteenth Division to the north of it, extending close to the Ancre, where Higginson’s Twelfth Division lay astride of that marshy stream. North of this again was the Forty-seventh Division (Gorringe), together with a brigade of the Thirty-third American Division. Two days before the great advance, on August 6, the Twenty-seventh Würtemburg Division had made a sudden strong local attack astride of the Bray — Corbie Road, and had driven in the Eighteenth Divisional front, taking some hundreds of prisoners, though the British counter-attack regained most of the lost ground on the same and the following days. This unexpected episode somewhat deranged the details of the great attack, but the Eighteenth played its part manfully none the less, substituting the 36th Brigade of the Twelfth Division for the 54th Brigade, which had been considerably knocked about. None of the British prisoners taken seem to have given away the news of the coming advance, but it is probable that the sudden attack of the Würtemburgers showed that it was suspected, and was intended to anticipate and to derange it.

In the first phase of the attack the little village of Sailly-Laurette on the north bank of the Somme was carried by assault by the 2/10th Londons. At the same moment the 174th Brigade attacked Malard Wood to the left of the village. There was a difficulty in mopping up the wood, for small German posts held on with great tenacity, but by 9 o’clock the position was cleared. The 173rd Brigade now went forward upon the really terrible task of getting up the slopes of Chipilly Hill under the German fire. The present chronicler has looked down upon the line of advance from the position of the German machine-guns and can testify that the affair was indeed as arduous as could be imagined. The village of Chipilly was not cleared, and the attack, after several very-gallant attempts, was at a stand. Meantime the 53rd Brigade on the left had got about half-way to its objective and held the ground gained, but could get no farther in face of the withering fire. Farther north, however, the Twelfth Division, moving forward upon the northern slopes of the Ancre, had gained its full objectives, the idea being that a similar advance to the south would pinch out the village of Morlancourt. There was a time in the attack when it appeared as if the hold-up of the Eighteenth Division would prevent Vincent’s 35th Brigade, on the right of the Twelfth Division, from getting forward, but the situation was restored by a fine bit of work by the 1st Cambridgeshires, who, under Colonel Saint, renewed the attack in a most determined way and finally were left with only 200 men standing, but with 316 German prisoners as well as their objective. A wandering tank contributed greatly to this success.