Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1384 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

From now onwards the fighting upon the Roye and Montdidier front (both towns passed soon into German possession) was no longer connected with the Third Corps. The position to the south of the Oise showed that the Fifty-eighth British Division held from Barisis to Manicamp. Thence to Bretigny was the One hundred and twenty-fifth French Division. Thence to the east of Varennes were the Fifty-fifth French Division, with cavalry, and the First French Division up to Sempigny. Thence the line ran in an irregular curve through Lassigny to Canny, the enemy being well past that line on the north, and the direction of attack being rather from the north-west. On the morning of March 28 orders were issued that the remains of the Third Corps should be transferred to the north, where they should join their comrades of the Fifth Army, from whom they were now separated by a considerable distance. Within the next two days, after some difficulties and delays in extricating the artillery, these orders were carried out, though it was not till some days later that the Fifty-eighth London Division could be relieved. This unit had not, save for the 173rd Brigade, been engaged in the recent fighting, but it had held a line of over ten miles of river, along the whole of which it was within touch with the enemy. One effort of the Germans to get across at Chauny on March 31 was met and repelled by the 16th Entrenching Battalion, who killed many of the assailants and captured nearly 100 prisoners.

So ended the vicissitudes of the Third Corps, which had the strange experience of being swept entirely away from the army to which it belonged, and finding itself under French command, and with French troops fighting upon either wing. Its losses were exceedingly heavy, including 20 heavy and Third 100 field-guns, with about 15,000 killed, wounded, or missing. The Fourteenth Division was the chief sufferer with 5880 casualties, 4500 of which came under the head of “Missing,” and represent the considerable detachments which were cut off in the first day of the battle. The losses of some of the battalions approached annihilation. In spite of all pressure and all misfortunes there was never a time when there was a break, and the whole episode was remarkable for the iron endurance of officers and men in the most trying of all experiences — an enforced retirement in the face of an enemy vastly superior both in numbers and in artillery support. When we realise how great was the disparity it is amazing how the line could have held, and one wonders at that official reticence which allowed such glorious epics to be regarded as part of a great military disaster. Against the two and a half British divisions which were in the line on March 21 there were arrayed seven German divisions, namely, the Fifth Guards, First Bavarians, Thirty-fourth, Thirty-seventh, One hundred and third. Forty-seventh, and Third Jaeger. There came to the Third Corps as reinforcements up to March 26 two British cavalry divisions, one French cavalry division, and three French infantry divisions, making eight and a half divisions in all, while seven more German divisions, the Tenth, Two hundred and eleventh, Two hundred and twenty-third, Eleventh Reserve, Two hundred and forty-first, Thirty-third, and Thirty-sixth came into line, making fourteen in all. When one considers that these were specially trained troops who represented the last word in military science and efficiency, one can estimate that an unbroken retreat may be a greater glory than a victorious advance.

Every arm — cavalry, infantry, and artillery — emerged from this terrible long-drawn ordeal with an addition to their fame. The episode was rather a fresh standard up to which they and others had to live than a fault which had to be atoned. They fought impossible odds, and they kept on fighting, day and night, ever holding a fresh line, until the enemy desisted from their attacks in despair of ever breaking a resistance which could only end with the annihilation of its opponents. Nor should the organisation and supply services be forgotten in any summing up of the battle. The medical arrangements, with their self-sacrifice and valour, have been already dealt with, but of the others a high General says: “A great strain was also cast upon the administrative staffs of the army, of corps and of divisions, in evacuating a great mass of stores, of hospitals, of rolling stock, of more than 60,000 non-combatants and labour units, while at the same time supplying the troops with food and ammunition. With ever varying bases and depots, and eternal rapid shifting of units, there was hardly a moment when gun or rifle lacked a cartridge. It was a truly splendid performance.”

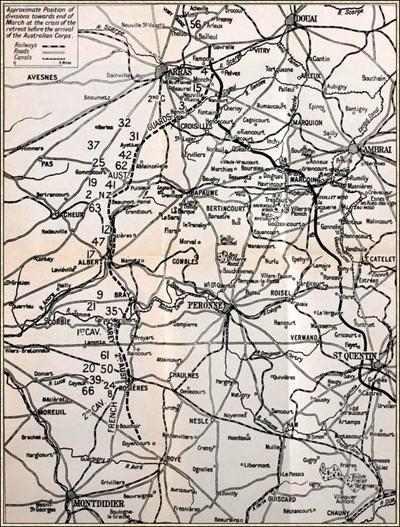

We have now traced the movements and the final positions of the eight corps which were involved in this terrible battle from the foggy morning which witnessed the German attack, up to those rainy days of early April which showed a stable line — a line which in spite of occasional oscillations continued from that date until the great British victory in August, to mark the point of equilibrium of the giant forces which leaned from east and from west. In this account we have seen the Seventeenth and Sixth Corps in the north fall back upon Arras and the Vimy Ridge, where they turned and dealt their pursuers such a blow that the battle in that sector was at an end. We have seen the Fourth, Fifth, and Seventh Corps struggling hard to make a line from Arras to Albert and down to the Somme; we have seen the Nineteenth Corps covering a huge front and finally holding firm near Villers-Bretonneux, and we have seen the Eighteenth and Third Corps intermixed with our French Allies helping to determine the line in the southern area of the great field of battle. That line running just to the west of Montdidier, Moreuil, and Albert was destined for four months to be a fixed one, though it was advanced during that time by the splendid audacity of the Australians, who gave their opponents no rest, and finally, with the help of the British Eighth Division, entirely re-won the town of Villers-Bretonneux when it was temporarily lost, and extended our outposts a mile or more to the east of it, as will be presently described. Save for this action there was no movement of importance during that time, though the general set of the tide was rather eastwards than westwards.

One cannot leave so vast a theme as the second battle of the Somme without a few words as to the general impression left upon the mind of the writer by the many documents bearing upon the subject which he has had to peruse. In the first place, we cannot possibly deny that it was a great German victory, and one which was well earned, since it depended upon clever and new dispositions entailing laborious preparation with the intelligent and valiant co-operation of officers and men. The overpowering force of the blow, while it removed all reproach from those who had staggered back from it, depended upon the able way in which it was delivered. Having said so much, we must remind the German commentator that he cannot have it both ways, and that if a gain of guns, prisoners, and ground which fails to break the line is, as we admit, a victory to the Germans, then a similar result is a victory to the British also. He cannot claim the second battle of the Somme to be a victory, and yet deny the term to such battles as Arras, Messines, and Passchendaele. The only difference is that the Germans really did try to break the line upon March 21, and failed to do so, while no such design was in General Haig’s mind during the battles of 1917, save perhaps in the last series of operations.

There was a regrettable tendency after the battle to recriminations in the Press, and General Gough, who had been the head of the Fifth Army, was sacrificed without any enquiry as to the dominant force which he had to face, or as to the methods by which he mitigated what might have been a really crushing disaster. It can be safely stated that in the opinion of many of those who are in the best position to know and to judge, there was absolutely nothing upon the military side which could have been bettered, nor has any suggestion ever been made of anything which was left undone.

Position at the Close of the Great Retreat, March 30

The entrenching had been carried out for several months with an energy which raised protests from the men who had to do it. There might almost be room for the opposite criticism that in the constant work of the navvy the training of the soldier had been unduly neglected; but that was the result of the unavoidable scarcity of non-military labour. The extension of the front was undoubtedly too long for the number of men who had to cover it; but this was done at the express request of the French, who had strong military reasons for drawing out and training a number of their divisions. It was taking a risk undoubtedly, but the risk was forced upon the soldiers, and in any case the French have taken risks before now for us. The blowing up of the bridges was well done, and the only exception seems to have been in the case of railway bridges which, for some reason, were taken out of the hands of the army commander. The reserves were insufficient and were perhaps too far back, but the first item at least depended upon the general weakness of manpower. Nowhere can one lay one’s hand upon any solid ground for complaint, save against the rogues and fools of Brest-Litovsk, who by their selfish and perjured peace enabled the Germans to roll a tidal wave of a million men from east to west, with the certainty that they would wash away the first dam against which they struck. If there is any military criticism to be made, it lies rather in the fact that the French help from the south was nearly sixty hours before it made itself felt at the nearest part of the British line, and also in the surprising number of draft reserves kept in England at that date. Within a month of the battle 350,000 had been sent to the front — a very remarkable feat, but a sign, surely, of an equally remarkable omission. Had ten emergency divisions of infantry been made out of the more forward of these drafts, had they been held ready in the rear zones, and had the actual existing reserves been pushed up to the front, it is safe to say that the German advance would have been stopped earlier and would probably not have got beyond the Peronne — Noyon line. If, as was stated in Parliament, it was confidently expected that the German attack would strike exactly where it did, then it does seem deplorable that the nearest reserve to the Fifth Army, a single division, had, through our weak man-power, to be kept at a three days’ journey from the point of danger. If, instead of searching the record of the General for some trace of weakness, our critics had realised the rapidity of his decision, with the moral courage and grasp of actuality which he showed by abandoning his positions — no easy thing for one of his blood and record — and falling back unbroken upon a new line of defence beyond the German heavy artillery, they could not have failed to admit that the country owes a deep debt of gratitude to General Gough. Had he hesitated and his army been isolated and destroyed, the whole war might well have taken a most sinister turn for the worse.

Granting, however, that the disaster was minimised by the prompt appreciation of the situation by the General in command, by the splendid work of his four corps-commanders, and by the co-operation of every one concerned, it is still undeniable that the losses were very heavy, and the result, even after making every allowance for German wastage, a considerable military disaster. In killed, wounded, and missing in the Fifth Army alone the figures could not be less than 50,000, including Feetham and Malcolm, army divisional generals, with Dawson, Bailey, White, Bellingham, and numerous other brigadiers and senior officers. In field-guns 235 were lost or destroyed out of

VIII. THE SOMME FRONT FROM APRIL 1 ONWARDS

The last waves of the storm — The Twelfth Division at Albert — The Forty-seventh Division at Aveluy Wood — The Australians in the south — Capture of Villeis-Bietonneux by the Germans — Recapture by Australians and Eighth Division — Fierce fighting — The first turn of the tide

THE limit and results of the second battle of the Somme had been defined when the Australians, New Zealanders, Second Canadians, and fresh British divisions took the place of their exhausted comrades towards the end of March. The German reserves, great as they were, were, nearly exhausted, and they had no more men to put into the fight. The final line began to clearly define itself, running from a few miles east of Arras where the Seventh and Sixth Corps had struck back so heavily at the German pursuit, through Neuville Vitasse, Boyelles, Ayette, Bucquoy, Hébuterne, Auchonvillers, Aveluy, just west of Albert, Denancourt, Warfusée, and Marcelcave. The worst storm was over, but even as the sinking sea will still send up one great wave which sweeps the deck, so the German battle front would break from time to time into a spasm of energy, which could effect no great purpose and yet would lead to a considerable local engagement. These episodes must at least be indicated in the order of their occurrence.

One great centre of activity was the ruined town of Albert, for the Germans were able to use it as a covered approach, and thus mass their troops and attempt to break through to the westward. The order of divisions in this sector showed that the Sixty-third and Forty-seventh, still fighting in spite of their wounds, were to the immediate north-west. The Twelfth Division was due west. South-west was the Third Division of Australians and south of these the Fourth. On each of these, and sometimes upon all of them, the strain was very great, as the Germans struggled convulsively to burst the bonds of Albert. It should be noted that the Fifth Army had for the time passed out of being, and that all the southern end of the line was now held by the Fourth Army under General Rawlinson.

The main attack upon the Albert sector was on April 4, when the Germans made a violent effort, and the affair reached the proportions of a considerable battle. About eight in the morning the action began by a severe and sudden attack upon the Australian Division

North of the Australians was the Twelfth Division with the 35th and 36th Brigades in the line, in that order from the south. The temporary recoil of the Australians rendered the 35th Brigade vulnerable, and the Germans with their usual quick military perception at once dashed at it. About 1 o’clock they rushed forward in two waves, having built up their formation under cover of the ruined houses of Albert. The attack struck in between the 7th Suffolks and 9th Essex, but the East Anglians stood fast and blew it back with their rifle-fire, much helped by the machine-guns of the 5th Berks. Farther north the attack beat up against the left of the Forty-seventh and the right of the Sixty-third Divisions, but neither the Londoners nor the naval men weakened. The pressure was particularly heavy upon the Forty-seventh, and some details of the fighting will presently be given. The next morning, April 5, saw the battle still raging along the face of these four divisions. The Germans attempted to establish their indispensable machine-guns upon the ridge which they had taken on the south, but they were driven off by the Australians. The 36th Brigade in the north of the Albert sector had lost some ground at Aveluy, but about noon on April 5 the 9th Royal Fusiliers with the help of the 7th Sussex re-established the front, though the latter battalion endured very heavy losses from an enfilade fire from a brickfield. The 5th Berks also lost heavily on this day. So weighty was the German attack that at one time the 4th Australians had been pushed from the high ground, just west of the Amiens-Albert railway, and the 35th Brigade had to throw back a defensive wing. The position was soon re-established, however, though at all points the British losses were considerable, while those of the Germans must have been very heavy indeed.

It has been stated that to the north of the Twelfth Division, covering Bouzincourt and partly occupying Aveluy Wood, was the Forty-seventh Division (Gorringe), which had been drawn out of the line, much exhausted by its prolonged efforts, some days before, but was now brought back into the battle. It stood with the 15th and 20th London of the 140th Brigade on the right, while the 23rd and 24th of the 142nd Brigade were on the left. Units were depleted and the men very weary, but they rose to the crisis, and their efforts were essential at a time of such stress, for it was felt that this was probably the last convulsive heave of the dying German offensive. It was on April 5 that the German attack from the direction of Albert spread to the front of the Forty-seventh Division. The bombardment about

About 9 o’clock the right brigade was also involved in the fighting, the enemy advancing in force towards Aveluy Wood. Here also the assault was very desperate and the defence equally determined. The 15th (Civil Service Rifles) was heavily attacked, and shortly afterwards the Blackheath and Woolwich men of the 20th Battalion saw the enemy in great numbers upon their front. The whole line of the division was now strongly engaged. About

At 11.40 the 23rd London, which had suffered from the German penetration of its left company, was exposed all along its line to machine-gun fire from its left rear, where the enemy had established three posts. The result was that the position in Aveluy Wood had to be abandoned. The 22nd London from the reserve brigade was now pushed up into the firing-line where the pressure was very great. The weight of the attack was now mainly upon the 20th, who held their posts with grim determination in spite of very heavy losses, chiefly from trench mortars and heavy machine-guns. It was a bitter ordeal, but the enemy was never able to get nearer than

At four in the afternoon, after a truly terrible day, the Forty-seventh Division determined to counter-attack, and the 22nd Battalion was used for this purpose. They had already endured heavy losses and had not sufficient weight for the purpose, though eight officers and many men had fallen before they were forced to recognise their own inability. The failure of this attack led to a further contraction of the line of defence. The Sixty-third Division on the left had endured a similar day of hard hammering, and it was now very exhausted and holding its line with difficulty. For a time there was a dangerous gap, but the exhausted Germans did not exploit their success, and reserves were hurried up from the Marines on the one side and from the 142nd Brigade on the other to fill the vacant position.

When night fell after this day of incessant and desperate fighting the line was unbroken, but it had receded in the area of Aveluy Wood and was bent and twisted along the whole front. General Gorringe, with true British tenacity, determined that it should be re-established next morning if his reserves could possibly do it. Only one battalion, however, was available, the pioneer 4th Welsh Fusiliers, who had already done conspicuous service more than once during the retreat. An official document referring to this attack states that “no troops could have deployed better or advanced more steadily under such intense fire, and the leadership of the officers could not have been excelled.” The casualties, however, were so heavy from the blasts of machine-gun fire that the front of the advance was continually blown away and no progress could be made. Two platoons upon the left made some permanent gain of ground, but as a whole this very gallant counter-attack was unavailing.

This attack near Albert on April 4 and 5 was the main German effort, but it synchronised with several other considerable attacks at different points of the line. One was just north of Warfusée in the southern April 5. sector, where once again the Australians were heavily engaged and prevented what at one time seemed likely to be a local break-through. As it was the line came back from Warfusée to Vaire, where the Australian supports held it fast. Farther north the Fourth Australian Division was sharply attacked opposite Denancourt, and had a very brisk fight in which the 13th Brigade, and more particularly the 52nd Regiment, greatly distinguished itself. The object of the fight was to hold the railway line and the position of the Ancre. The tenacity of the Australian infantry in the face of incessant attacks was most admirable, and their artillery, ranging upon the enemy at

The village of Hangard and Hangard Wood were at that time the points of junction between the French and British armies. The extreme right unit of the British was Smith’s 5th Brigade of the Second Australian Division (Rosenthal). The 20th Battalion on the southern flank was involved on this and the following days in a very severe and fluctuating fight in which Hangard Wood was taken and lost several times. Colonel Bennett, an Australian veteran whose imperial services go back as far as the Suakin expedition, had to cover

About

The German commanders were well aware that if the line was to be broken it must be soon, and all these operations were in the hope of finding a fatal flaw. Hence it was that the attacks which began and failed upon April 4 extended all along the northern line on April 5. Thus the New Zealand Division on the left of the points already mentioned was involved in the fighting, the right brigade, consisting of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade, being fiercely attacked by some 2000 storm troops who advanced with great hardihood, and at the second attempt recaptured the farm of La Signy. The German officers seem upon this occasion to have given an example to their men which has often been conspicuously lacking. “A tall Wurtemburger,” says the New Zealand recorder, “ran towards our line with nine of his men. In one hand he carried a cane, and over his arm a light waterproof coat. He was a fine big fellow over six feet high.... Just at the critical moment some Lewis-gunners took a hand in the business, the officer was shot dead, and most of the others were killed or wounded.”

On the left of the New Zealanders the attack was extended to the road between Ayette and Bucquoy. Here a brigade of the Thirty-seventh Division in the south and of the Forty-second in the north were heavily attacked and Bucquoy was taken, but before the evening the defenders returned and most of the lost ground was regained. The right of the Thirty-seventh Division had advanced in the morning upon Rossignol Wood, that old bone of contention, and had in a long day’s struggle got possession of most of it. Three machine-guns and 130 men were the spoils.

From this time onwards there were no very notable events for some weeks in the Somme line, save for some sharp fighting in the Aveluy Wood sector on April 21 and