Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1362 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

The Twelfth Division formed the flank of Pulteney’s Third Corps. Upon its right was Snow’s Seventh Corps, the left-hand unit of which was the Fifty-fifth Division of Lancashire Territorials, which had not been involved in the advance, and indeed was nominally resting after its supreme exertions at Ypres where it had taken a notable part in battle after battle. It had been planned, however, that some demonstration should be made upon this front in order to divert the enemy’s forces and to correspond with the attack at Bullecourt upon the north. This was carried out by the 164th Brigade and may have had the desired effect although it gave no permanent gain. A point called the Knoll, with an adjacent farm, was carried by the stormers and was held for most of the day, but they were forced back to their own old lines in the evening, after a long day of battle in which they incurred such heavy losses that the brigade was seriously crippled at a later date when the full strength of the division was urgently needed. This ended the first day of the battle, which represented a considerable victory, and one which vindicated the enterprise and brain-power of the British inventor and engineer as much as the valour of the soldier. The German line was deeply indented over a front of

There were no operations of any importance during the night of the 20th, but early upon November 21 the British line began to move forward once more, the same divisions being engaged in the advance. In the north the Ulstermen, who had attained the line of the Cambrai-Bapaume road, crossed that boundary and pushed onwards up the slope for about a mile until they reached the outskirts of the village of Moeuvres which they were unable to retain. It was soon apparent, both here and at other points along the line, that the Germans with their usual military efficiency had brought up their reserves even more rapidly than had been expected, and the resistance at Moeuvres was so determined that the tired division was unable to overcome it. The 169th Brigade of the Fifty-sixth Division pushed up on the left of the Ulstermen and occupied the German outpost line, from which they were able later to attack the main Hindenburg Line.

The Sixty-second Division upon the right of the Ulstermen had got to the edge of Anneux upon the night before, and now the 2/4th West Ridings were able to complete their conquest. The 186th Brigade then drove across the Cambrai road and reached the edge of the Considerable plantation called Bourlon Wood which rises upon a swelling hill, the summit being so marked in that gently undulating country that it becomes a landmark in the distance. Here there was very strong opposition, with so murderous a machine-gun fire that all progress was arrested, though a number of tanks drove their way in among the trees in an effort to break down the resistance. In the meantime the flank of the Yorkshiremen had been protected by the capture of the village of Cantaing with several hundred more prisoners.

Early in the day the Fifty-first had got round the northern edge of Flesquières, the village which had held up the centre of the advance upon the first day. As a consequence it fell and the front was cleared for a further advance. The Scotch infantry was then able to make a rapid advance of nearly three miles, taking Cantaing with 500 prisoners upon the way, and winding up in front of the village of Fontaine-Nôtre-Dame, which they stormed in a very brilliant fashion with the aid of tanks and of some squadrons of the First Cavalry Division as already noted.

Farther south the Sixth and Twenty-ninth Divisions acting in close co- operation had pushed their way through Mesnières, where they met and defeated a counter-attack from the direction of Rumilly. It was clear that every hour the German line was thickening in this quarter. Whilst the Sixth cleared the ground upon the left, the Twenty-ninth pushed forward and reached Noyelle, where with the aid of those useful allies, the dismounted troopers of the First and Fifth Cavalry Divisions, including the Umballa Brigade of Indians, they made goad the village as already described.

In the meantime the 10th Rifle Brigade of the Twentieth Division upon the right had first taken and then lost Les Rues des Vignes, an important position upon the British side of the canal. In the afternoon the 11th Rifle Brigade managed to cross the canal and endeavoured to push up towards Crèvecoeur, but at this point the river Scheldt ran on the farther side and offered an impediment which could not be crossed. Orders were issued by General Byng that a fresh attempt should be made next morning, but the troops were weary and the losses heavy so the instructions were cancelled and the line remained unaltered at this point.

The end of the second day of battle found the British Command faced with a difficult problem, and we have the Field-Marshal’s own lucid analysis of the alternative courses open, and as to the reasons which prompted his decision. The capture of Cambrai had never been the goal of the operations, though a cavalry raid which would have disorganised the communications through that town had at one time seemed possible. A turning of the line to the south with the co-operation of some French divisions which were ready upon the spot, was part of the original conception, and was baulked by the insufficient hold established upon the farther side of the Canal de l’Escaut. But the central idea had been the capture of the high ground of Bourlon Hill and Wood for with this in British possession a considerable stretch of the defensive German line would lie open to observed artillery fire, and its retention would probably mean a fresh withdrawal to the east. It had been hoped that the goal would have been attained within forty-eight hours, but this time had elapsed and the assailants were at the bottom instead of the summit of the hill, with a resistance in front which was continually growing more obstinate. What was to be done?

The troops could not remain where they were, for the Bourlon Hill overlooked their position. They must carry it or retire. There was something to be said for the latter policy, as the Flesquières Ridge could be held and the capture of 10,000 prisoners and over 100 guns had already made the victory a notable one, while the casualties in two days were only 9000. On the other hand, while there is a chance of achieving a full decision it is hard to abandon an effort; reinforcements were coming up, and the situation in Italy demanded a supreme effort upon the Western front. With all these considerations in his mind the Field-Marshal determined to carry on.

November 22 was spent in consolidating the ground gained, in bringing up reinforcements, and in resting the battle- weary divisions. There was no advance upon the part of the British during the day, but about one o’clock in the afternoon the Germans, by a sudden impetuous attack, regained the village of Fontaine and pushed back the Fifty-first Division in this quarter. No immediate effort was made to regain it, as this would be part of the general operations when the new line of attack was ready to advance. Earlier in the day the Germans had thrown themselves upon the front of the Sixty-second, driving back its front line, the 2/6th and 2/8th West Yorkshires, to the Bapaume-Cambrai road, but the Yorkshiremen shook themselves together, advanced once more, and regained the lost ground with the help of the 2/4th York and Lancasters. The Germans spent this day in building up their line, and with their better railway facilities had probably the best of the bargain, although the British air service worked with their usual utter self-abnegation to make the operation difficult.

The new advance began upon the night of November 22, when the 56th Londoners reinforced the Ulsters upon the left of the line on the outskirts of the village of Moeuvres. To the west of the village, between it and the Hindenburg Line, was an important position, Tadpole Copse, which formed a flank for any further advance. This was carried by a surprise attack in splendid style by the 1st Westminsters of the 169th Brigade. During the day both the Londoners and the Ulstermen tried hard, though with limited success, to enlarge the gains in this part of the field.

The attack was now pointing more and more to the north, where the wooded height of Bourlon marked the objective. In the southern part the movements of the troops were rather holding demonstrations than serious attacks. The real front of battle was marked by the reverse side of the Hindenburg Line upon the left, the hill, wood, and village of Bourlon in the centre, and the flanking village of Fontaine upon the right. All of these were more or less interdependent, for if one did not take Bourlon it was impossible to hold Fontaine which lay beneath it, while on the other hand any attack upon Bourlon was difficult while the flanking fire of Fontaine was unquenched. From Moeuvres to Fontaine was a good six miles of most difficult ground, so that it was no easy task which a thin line of divisions was asked, to undertake — indeed only four divisions were really engaged, the Thirty-sixth and Fifty-sixth on the left, the Fortieth in the centre, and the Fifty-first on the right.

The operations of November 23 began by an attack by the enduring Fifty-first Division, who had now been four days in the fighting line against Fontaine Village — an attempt in which they were aided by a squadron of tanks. Defeated in the first effort, they none the less renewed their attack in the afternoon with twelve more tanks, and established themselves close to the village but had not sufficient momentum to break their way through it. There they hung on in most desperate and difficult fighting, screening their comrades in the main Bourlon attack, but at most grievous cost to themselves.

Meanwhile the Thirty-sixth Division had again attacked Moeuvres, and at one time had captured it all, save the north-west corner, but heavy pressure from the enemy prevented them retaining their grasp of it. The two brigades of this division upon the east of the canal were unable, unfortunately, to make progress, and this fact greatly isolated and exposed the Fortieth Division during and after its attack.

This main attack was entrusted to the Fortieth Division, a unit which had never yet found itself in the full lurid light of this great stage, but which played its first part very admirably none the less. It was a terrible obstacle which lay in front of it, for the sloping wood was no less than

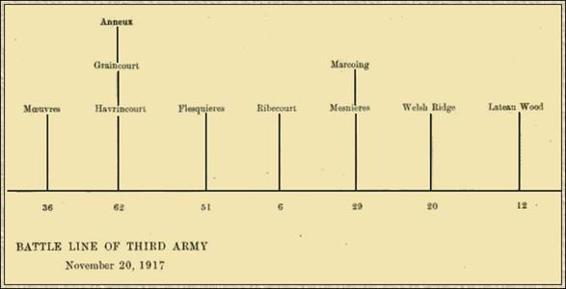

Battle Line of Third Army, November 20, 1917

It was arranged that the tanks should, so far as possible, go down those rides which are so conspicuous a feature of every French forest, while the infantry should move up between them. The 119th Brigade moved forward with the 19th Welsh Fusiliers upon the right, the 12th South Wales Borderers on the left, while the 17th Welsh were in close reserve. It was the second occasion in the war when a splendid piece of woodland fighting was carried through by the men of the Principality, and even Mametz was not a finer performance than Bourlon. They rapidly broke through the German front line, capturing numerous prisoners and machine-guns. The Colonel of the Fusiliers pushed his way forward to the north edge where he established posts, while the flank of the Welsh Borderers brushed the village of Bourlon and got north of that point. The 17th Welsh meanwhile formed defensive flanks upon either side, while the 18th Welsh came up to reinforce, and pushed ahead of their comrades with the result that they were driven in by a violent counter-attack. The line was re-established, however, and before one o’clock the 119th Brigade were dug in along the whole northern edge of the forest. It was a fine attack and was not marred by excessive losses, though Colonel Kennedy of the 17th Welsh was killed. Among many notable deeds of valour was that of Sergeant-Major Davies of the 18th Welsh, who knelt down in the open and allowed his shoulder to be used as the rest for a Lewis gun, until a bullet struck him down.