Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1303 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

Upon February 20 the adventure of the Dardanelles was begun by a bombardment of the outer forts by the Allied Fleets. The British ships engaged in these operations were pre-Dreadnought battleships, with the notable exception of the new cruiser

Queen Elizabeth

. On March

Ocean

and the

Irresistible

were lost by floating torpedoes. On May 13 we lost in the same locality the

Goliath

, which was also torpedoed in a very gallant surface attack delivered at night by a Turkish or German boat. On the 26th the

Triumph

fell a victim to a submarine in the same waters. The other naval events of the year include numerous actions of small craft with varying results, and the final destruction of the

Dresden

, the

Königsberg

, and every other German warship left upon the face of the waters. The British anti-submarine devices in home waters reached a high point of efficiency, and the temporary subsidence of submarine warfare is to be attributed rather to the loss of these vessels than to any remonstrances upon the part of neutrals.

Some allusion should be made to the Zeppelins which were malevolently active during the year, but whose efficiency fortunately fell very far short of either the activity or the malevolence. Instead of proving a blessing to mankind, the results of the energy and ingenuity of the aged German inventor were at once turned to the most devilish use conceivable, for their raids effected no possible military object, but caused the death or mutilation of numerous civilians, including a large number of women and children. The huge bombs were showered down from the airships with no regard at all as to whether a legitimate mark lay beneath them, and the huge defenceless city of London was twice attacked on the plea that the possession of munition works made the whole of it a fortress. The total result of all the raids came to about 1500 killed and wounded. It is probable that the destruction of the invading of airships in 1916 killed more German fighting adults than were killed in England by all their raids combined. They effected nothing decisive save the ignominy of the murderers who used them.

Of the Dardanelles Campaign nothing need be said, since it will be fully treated in many separate accounts, save that our general position was greatly weakened by the large number of vessels needed for the conduct of these operations, nor did we profit much by their abandonment since the call of Salonica soon became equally insistent. We were able during the year to continue the absorption of the German Colonial Empire, none of which, save East Africa, remained intact at the end of it. Egypt was successfully defended against one or two half-hearted advances upon the part of the Turks. The Mesopotamian Campaign, however, had taken at the close of the year a sinister turn, for General Townshend, having pushed forward almost to the gates of Bagdad with a very inadequate force, was compelled to retreat to Kut, where he was surrounded and besieged by a considerable Turkish army. The defence was a heroic one, and only ended in the spring of 1916, when the starving survivors were forced to surrender.

As to the affairs of our Allies, some allusion will be made later to the great French offensive in Champagne, which was simultaneous with our own advance at Loos. For the rest there was constant fighting along the line, with a general tendency for the French to gain ground though usually at a heavy cost. The year, on the other hand, had been a disastrous one for the Russians who, half-armed and suffering terrible losses, had been compelled to relinquish all their gains and to retreat for some hundreds of miles. As is now clear, the difficulties in the front were much increased by lamentable political conditions, including treachery in high places in the rear. For a time even Petrograd seemed in danger, but thanks to fresh supplies of the munitions of war from Britain and from Japan they were able at last to form a firm line from Riga in the north to the eastern end of the Romanian frontier in the south.

The welcome accession of Italy upon May 23 and the lamentable defection of Bulgaria on October 11 complete the more salient episodes of the year.

VII. THE BATTLE OF LOOS

The First Day — September 25

General order of battle — Check of the Second Division — Advance of the Ninth and Seventh Divisions — Advance of the First Division — Fine progress of the Fifteenth Division — Capture of Loos — Work of the Forty-seventh London Division

WHILST the Army had lain in apparent torpidity during the summer a torpidity which was only broken by the sharp engagements at Hooge and elsewhere great preparations for a considerable attack had been going forward. For several months the sappers and the gunners had been busy concentrating their energies for a serious effort which should, as it was hoped, give the infantry a fair chance of breaking the German line. Similar preparations were going on among the French, both in Foch’s Tenth Army to the immediate right of the British line, and also on a larger scale in the region of Champagne. Confining our attention to the British effort, we shall now examine the successive stages of the great action in front of Hulluch and Loos the greatest battle, both as to the numbers engaged and as to the losses incurred, which had ever up to that date been fought by our Army.

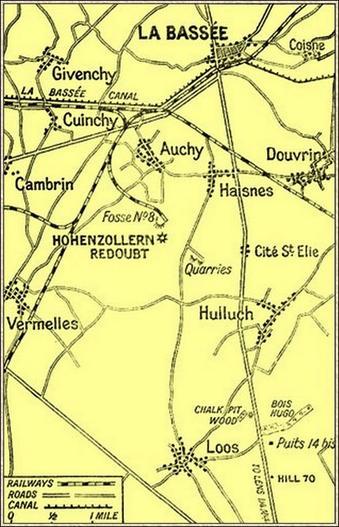

Loos District

The four days which preceded the great attack of September 25 were days of great activity. An incessant and severe bombardment was directed upon the German lines along the whole front, but especially in the sector to the immediate south of the La Bassée Canal, where the main thrust was to be made. To this severe fire the Germans made hardly any reply, though whether from settled policy or from a comparative lack of munitions is not clear. On each of the days a feint attack was made upon the German line so far as could be done without actually exposing the men. The troops for the assault were gradually brought into position, and the gas-cylinders, which were to be used for the first time, were sunk in the front parapets.

The assault in the main area was to extend from the La Bassée Canal in the north to the village of Grenay in the south, a front of about seven miles, and it was to be supported and supplemented by many subsidiary attacks along the whole line up to the Ypres salient, and northwards still to where the monitors upon the coast held the German coastguards to their sand-dunes. For the moment we will deal only with the fortunes of the main attack. This was to be delivered by two army corps, both belonging to Haig’s First Army, that tempered blade which has so often been the spear-head for the British thrust. The corps were the First (Hubert Gough’s) and the Fourth (Rawlinson’s). It will be remembered that a British army corps now consisted of three divisions, so that the storming line was composed of six divisions, or about seventy thousand infantry.

The line of the advance was bisected by a high road from Vermelles to Hulluch. This was made the boundary line between the two attacking corps. To the left, or north of this road, was the ground of the First Corps; to the right, or south, of the Fourth.

The qualities of the Regular and Territorial regiments had already been well attested. This was the first occasion, however, when, upon a large scale, use was made of those new forces which now formed so considerable a proportion of the whole. Let it be said at once that they bore the test magnificently, and that they proved themselves to be worthy of their comrades to the right and the left. It had always been expected that the new infantry would be good, for they had in most cases been under intense training for a year, but it was a surprise to many British soldiers, and a blow to the prophets in Berlin, to find that the scientific branches, the gunners and the sappers, had also reached a high level. “Our enemy may have hoped,” said Sir John French, “not perhaps without reason, that it would be impossible for us, starting with such small beginnings, to build up an efficient artillery to provide for the very large expansion of the Army. If he entertained such hopes he has now good reason to know that they have not been justified by the result. The efficiency of the artillery of the new armies has exceeded all expectations.” These were the guns which, in common with many others of every calibre, worked furiously in the early dawn of Saturday, September 25, to prepare for the impending advance. The high explosives were known to have largely broken down the German system of defences, but it was also known that there were areas where the damage had not been great and where the wire entanglements were still intact. No further delay could be admitted, however, if our advance was to be on the same day as that of the French. The infantry, chafing with impatience, were swarming in the fire trenches. At

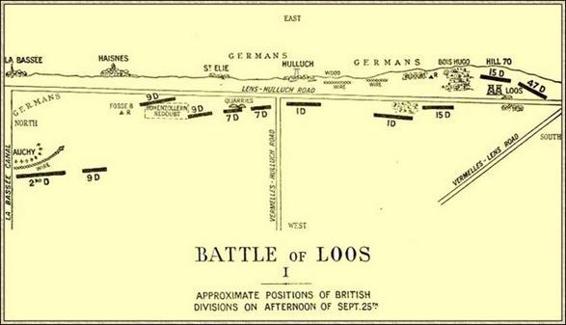

The following rough diagram of the action will help the reader to understand the order in which the six divisions attacked, and in a very rough way the objectives in front of them. It is impossible to describe simultaneously the progress of so extended a line.

Battle of Loos

It will be best, therefore, to take the various divisions from the northern end, and to follow the fortunes of each until it reached some definite limit. Afterwards an attempt will be made to co-ordinate these results and show their effects upon each other.

The second regular division (Home), acting upon the extreme left of the main attack, had two brigades north of the La Bassée Canal and one to the south. The most northern was the 5th (Cochrane’s), and its operations really formed part of the subsidiary attacks, and will be treated under that head. South of it was the 6th (Daly’s), to the immediate north of the canal. The gas, drifting slowly up the line before a slight southern breeze, had contaminated the air in this quarter, and many of the men were suffering from the effects. None the less, at half-past six the advance was made in a most dashing manner, but the barbed wire defences were found to be only partially damaged and the trenches to be intact, so no progress could be made. The 2nd South Staffords and 1st King’s Liverpools on the left and right reached the German position, but in face of a murderous fire were unable to make good their hold, and were enduring heavy losses, shared in a lesser degree by the 1st Rifles and 1st Berks in support. Upon their right, south of the canal, was the 19th Brigade (Robertson). The two leading regiments, the 1st Middlesex and 2nd Argylls, sprang from the trenches and rushed across the intervening space, only to find themselves faced by unbroken and impassable wire. For some reason, probably the slope of the ground, the artillery had produced an imperfect effect upon the defences of the enemy in the whole sector attacked by the Second Division, and if there is one axiom more clearly established than another during this war, it is that no human heroism can carry troops through uncut wire. They will most surely be shot down faster than they can cut the strands. The two battalions lay all day, from morning till dusk, in front of this impenetrable obstacle, lashed and scourged by every sort of fire, and losing heavily. Two companies of the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers, who gallantly charged forward to support them, shared their tragic experience. It was only under the cover of dusk that the survivors were able to get back, having done nothing save all that men could do. Their difficult situation was rendered more desperate by the fact that the wind drifted the gas that filthy and treacherous ally over a portion of the line, and some of our soldiers were poisoned by the effects. The hold-up was the more unfortunate, as it left the Germans the power to outflank the whole advance, and many of the future difficulties arose from the fact that the enemy’s guns were still working from Auchy and other points on the left rear of the advancing troops. In justice to the Second Division, it must be remembered that they were faced by the notoriously strong position called “the railway triangle,” and also that it is on the flanking units The that the strain must especially fall, as was shown equally clearly upon the same day in the great French advance in Champagne.

The advance of the next division, the Ninth Scottish Division (Thesiger’s) of the new armies, was of a most energetic nature, and met with varying fortunes according to the obstacles in their path. The valour and perseverance of the men were equally high in each of its brigades. By an unfortunate chance, General Landon, the officer who had played so essential a part on the fateful October 31, 1914, and who had commanded the Ninth Division, was invalided home only two days before the battle. His place was taken by General Thesiger, who had little time in which to get acquainted with his staff and surroundings. The front to be assaulted was of a most formidable nature. This Hohenzollern Redoubt jutted forward from the main German line, and was an enclosure seamed with trenches, girdled with wire, and fringed with machine- guns. Behind and to the north of it lay the slag-heap Fosse 8. The one favourable point lay in the fact that the attacking infantry had only a hundred yards to cross, while in the other parts of the line the average distance was about a quarter of a mile.

The attack of the Ninth Division was carried out with two brigades, the 26th (Ritchie) and 28th (Dickens), with the 27th (Bruce) in close support.

Continuing the plan of taking each unit from the north, we will follow the tragic fortunes of the 28th Brigade on the left. This brigade seems to have been faced by the same unbroken obstacles which had held up their neighbours of the Second Division upon the left, and they found it equally impossible to get forward, though the attack was urged with all the constancy of which human nature is capable, as the casualty returns only too clearly show.

The most veteran troops could not have endured a more terrible ordeal or preserved a higher heart than these young soldiers in their first battle. The leading regiments were the 6th Scottish Borderers and the 11th Highland Light Infantry. Nineteen officers led the Borderers over the parapet. Within a few minutes the whole nineteen, including Colonel Maclean and Major Hosley, lay dead or wounded upon the ground. Valour could no further go. Of the rank and file of the Borderers some 500 out of 1000 were lying in the long grass which faced the German trenches. The Highland Light Infantry had suffered very little less. Ten officers and 300 men fell in the first rush before they were checked by the barbed wire of the enemy. Every accumulation of evil which can appal the stoutest heart was heaped upon this brigade not only the two leading battalions, but their comrades of the 9th Seaforths and 10th H.L.I, who supported them. The gas hung thickly about the trenches, and all of the troops, but especially the 10th H.L.I., suffered from it. Colonel Graham of this regiment was found later incoherent and half unconscious from poisoning, while Major Graham and four lieutenants were incapacitated in the same way. The chief cause of the slaughter, however, was the uncut wire, which held up the brigade while the German rifle and machine-gun fire shot them down in heaps. It was observed that in this part of the line the gas had so small an effect upon the enemy that their infantry could be seen with their heads and shoulders clustering thickly over their parapets as they fired down at the desperate men who tugged and raved in front of the wire entanglement. An additional horror was found in the shape of a covered trench, invisible until one fell into it, the bottom of which was studded with stakes and laced with wire. Many of the Scottish Borderers lost their lives in this murderous ditch. In addition to all this, the fact that the Second Division was held up exposed the 28th Brigade to fire on the flank. In spite of every impediment, some of the soldiers fought their way onwards and sprang down into the German trenches; notably Major Sparling of the Borderers and Lieutenant Sebold of the H.L.I, with a handful of men broke through all opposition. There was no support behind them, however, and after a time the few survivors were compelled to fall back to the trenches from which they had started, both the officers named having been killed. The repulse on the left of the Ninth Division was complete. The mangled remains of the 28th Brigade, flushed and furious but impotent, gathered together to hold their line against a possible counter-attack. Shortly after mid-day they made a second attempt at a forward movement, but 50 per cent of their number were down, all the battalions had lost many of their officers, and for the moment it was not possible to sustain the offensive.