Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1276 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

On leaving Antwerp it had been necessary to strike to the north in order to avoid a large detachment of the enemy who were said to be upon the line of the retreat. The boundary between Holland and Belgium is at this point very intricate, with no clear line of demarcation, and a long column of British somnambulists, staggering along in the dark after so many days in which they had for the most part never enjoyed two consecutive hours of sleep, wandered over the fatal line and found themselves in firm but kindly Dutch custody for the rest of the war. Some fell into the hands of the enemy, but the great majority were interned. These men belonged chiefly to three battalions of the 1st Brigade. The 2nd Brigade, with one battalion of the 1st, and the greater part of the Marines, made their way to the trains at St. Gilles-Waes, and were able to reach Ostend in safety. The remaining battalion of Marines, with a number of stragglers of the other brigades, were cut off at Morbede by the Germans, and about half of them were taken, while the rest fought their way through in the darkness and joined their comrades. The total losses of the British in the whole misadventure from first to last were about 2500 men — a high price, and yet not too high when weighed against the results of their presence at Antwerp. On October 10 the Germans under General Von Beseler occupied the city. Mr. Powell, who was present, testifies that 60,000 marched into the town, and that they were all troops of the active army.

It has already been described how the northern ends of the two contending armies were endeavouring to outflank each other, and there seemed every possibility that this process would be carried out until each arrived at the coast. Early in October Sir John French represented to General Joffre that it would be well that the British Army should be withdrawn from the Aisne and take its position to the left of the French forces, a move which would shorten its line of communications very materially, and at the same time give it the task of defending the Channel coast. General Joffre agreed to the proposition, and the necessary steps were at once taken to put it into force. The Belgians had in the meanwhile made their way behind the line of the Yser, where a formidable position had been prepared. There, with hardly a day of rest, they were ready to renew the struggle with the ferocious ravagers of their country. The Belgian Government had been moved to France, and their splendid King, who will live in history as the most heroic and chivalrous figure of the war, continued by his brave words and noble example to animate the spirits of his countrymen.

From this time Germany was in temporary occupation of all Belgium, save only the one little corner, the defence of which will be recorded for ever. Little did she profit by her crime or by the excuses and forged documents by which she attempted to justify her action. She entered the land in dishonour and dishonoured will quit it. William, Germany, and Belgium are an association of words which will raise in the minds of posterity all that Parma, Spain, and the Lowlands have meant to us — an episode of oppression, cruelty, and rapacity, which fresh generations may atone for but can never efface.

VII. THE LA BASSÉE — ARMENTIÈRES OPERATIONS

(From October 11 to October 31, 1914)

The great battle line — Advance of Second Corps — Death of General Hamilton — The farthest point — Fate of the 2nd Royal Irish — The Third Corps — Exhausted troops — First fight of Neuve Chapelle — The Indians take over — The Lancers at Warneton — Pulteney’s operations — Action of Le Gheir

IN accordance with the new plans, the great transference began upon October 3. It was an exceedingly difficult problem, since an army of more than 100,000 had to be gradually extricated by night from trenches which were often not more than a hundred yards from the enemy, while a second army of equal numbers had to be substituted in its place. The line of retreat was down an open slope, across exposed bridges, and up the slope upon the southern bank. Any alarm to the Germans might have been fatal, since a vigorous night attack in the middle of the operation would have been difficult to resist, and even an artillery bombardment must have caused great loss of life. The work of the Staff in this campaign has been worthy of the regimental officers and of the men. Everything went without a hitch. The Second Cavalry Division (Gough’s) went first, followed immediately by the First (De Lisle’s). Then the infantry was withdrawn, the Second Corps being the vanguard; the Third Corps followed, and the First was the last to leave. The Second Corps began to clear from its trenches on October 3-4, and were ready for action on the Aire-Bethune line upon October 11. The Third Corps was very little behind it, and the First had reached the new battle-ground upon the 19th. Cavalry went by road; infantry marched part of the way, trained part of the way, and did the last lap very often in motor-buses. One way or another the men were got across, the Aisne trenches were left for ever, and a new phase of the war had begun. From the chalky uplands and the wooded slopes there was a sudden change to immense plains of clay, with slow, meandering, ditch-like streams, and all the hideous features of a great coal-field added to the drab monotony of Nature. No scenes could be more different, but the same great issue of history and the same old problem of trench and rifle were finding their slow solution upon each. The stalemate of the Aisne was for the moment set aside, and once again we had reverted to the old position where the ardent Germans declared, “This way we shall come,” and the Allies, “Not a mile, save over our bodies.”

The narrator is here faced with a considerable difficulty in his attempt to adhere closely to truth and yet to make his narrative intelligible to the lay reader. We stand upon the edge of a great battle. If all the operations which centred at Ypres, but which extend to the Yser Canal upon the north and to La Bassée at the south, be grouped into one episode, it becomes the greatest clash of arms ever seen up to that hour upon the globe, involving a casualty list — Belgian, French, British, and German — which could by no means be computed as under 250,000, and probably over 300,000 men. It was fought over an irregular line, which is roughly forty miles from north to south, while it lasted, in its active form, from October 12 to November 20 before it settled down to the inevitable siege stage. Thus both in time and in space it presents difficulties which make a concentrated, connected, and intelligible narrative no easy task. In order to attempt this, it is necessary first to give a general idea of what the British Army, in conjunction with its Allies, was endeavouring to do, and, secondly, to show how the operations affected each corps in its turn.

During the operations of the Aisne the French had extended the Allied line far to the north in the hope of outflanking the Germans. The new Tenth French Army, under General Foch, formed the extreme left of this vast manoeuvre, and it was supported on its left by the French cavalry. The German right had lengthened out, however, to meet every fresh extension of the French, and their cavalry had been sufficiently numerous and alert to prevent the French cavalry from getting round. Numerous skirmishes had ended in no definite result. It was at this period that it occurred, as already stated, to Sir John French that to bring the whole British Army round to the north of the line would both shorten very materially his communications and would prolong the line to an extent which might enable him to turn the German flank and make their whole position impossible. General Joffre having endorsed these views, Sir John took the steps which we have already seen. The British movement was, therefore, at the outset an aggressive one. How it became defensive as new factors intruded themselves, and as a result of the fall of Antwerp, will be shown at a later stage of this account.

As the Second Corps arrived first upon the scene it will be proper to begin with some account of its doings from October 12, when it went into action, until the end of the month, when it found itself brought to a standstill by superior forces and placed upon the defensive. The doings of the Third Corps during the same period will be interwoven with those of the Second, since they were in close co-operation; and, finally, the fortunes of the First Corps will be followed and the relation shown between its doings and those of the newly arrived Seventh Division, which had fallen back from the vicinity of Antwerp and turned at bay near Ypres upon the pursuing Germans. Coming from different directions, all these various bodies were destined to be formed into one line, cemented together by their own dismounted cavalry and by French reinforcements, so as to lay an unbroken breakwater before the great German flood.

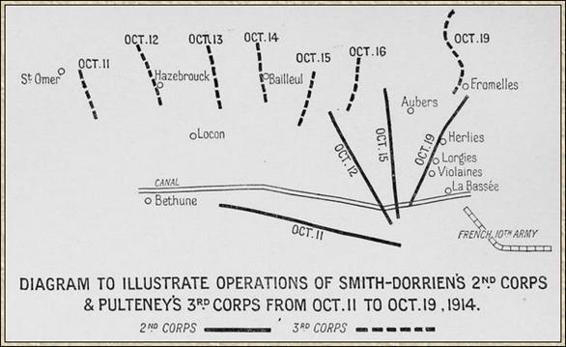

The task of the Second Corps was to get into touch with the left flank of the Tenth French Army in the vicinity of La Bassée, and then to wheel round its own left so as to turn the position of those Germans who were facing our Allies. The line of the Bethune-Lille road was to be the hinge, connecting the two armies and marking the turning-point for the British. On the 11th Gough’s Second Cavalry Division was clearing the woods in front of the Aire-Bethune Canal, which marked the line of the Second Corps. By evening Gough had connected up the Third Division of the Second Corps with the Sixth Division of the The Third Corps, which was already at Hazebrouck. On the 12th the Third Division crossed the canal, operations, followed by the Fifth Division, with the exception of the 13th Brigade, which remained to the south of it. Both divisions advanced more or less north before swinging round to almost due east in their outflanking movement. The rough diagram gives an idea of the point from which they started and the positions reached at various dates before they came to an equilibrium. There were many weary stages, however, between the outset and the fulfilment, and the final results were destined to be barren as compared with the exertions and the losses involved. None the less it was, as it proved, an essential part of that great operation by which the British — with the help of their good allies — checked the German advance upon Calais in October and November, even as they had helped to head them off from Paris in August and September. During these four months the little British Army, far from being negligible, as some critics had foretold would be the case in a Continental war, was absolutely vital in holding the Allied line and taking the edge off the hacking German sword.

Operations of Smith-Dorrien’s Second Corps and Pulteney’s Third Corps, October 11-19, 1914

The Third Corps, which had detrained at St. Omer and moved to Hazebrouck, was intended to move in touch with the Second, prolonging its line to the north. The First and Second British Cavalry Divisions, now under the command of De Lisle and of Gough, with Allenby as chief, had a role of their own to play, and the space between the Second and Third Corps was now filled up by a French Cavalry Division under Conneau, a whole-hearted soldier always ready to respond to any call. There was no strong opposition yet in front of the Third Corps, but General Pulteney moved rapidly forwards, brushed aside all resistance, and seized the town of Bailleul. A German position in front of the town, held by cavalry and infantry without guns, was rushed by a rapid advance of Haldane’s 10th Infantry Brigade, the 2nd Seaforths particularly distinguishing themselves, though the 1st Warwicks and 1st Irish Fusiliers had also a good many losses, the Irishmen clearing the trenches to the cry of “Faugh-a-Ballagh!” which has sounded so often upon battlefields of old. The 10th Brigade was on the left of the corps, and in touch with the Second Cavalry Division to the north. The whole action, with its swift advance and moderate losses, was a fine vindication of British infantry tactics. On the evening of October 15 the Third Corps had crossed the Lys, and on the 18th they extended from Warneton in the north to almost within touch of the position of the Second Corps at Aubers upon the same date.

The country to the south in which the Second Corps was advancing upon October 12 was an extraordinarily difficult one, which offered many advantages to the defence over the attack. It was so flat that it was impossible to find places for artillery observation, and it was intersected with canals, high hedgerows, and dykes, which formed ready-made trenches. The Germans were at first not in strength, and consisted for the most part of dismounted cavalry drawn from four divisions, but from this time onwards there was a constant fresh accession of infantry and guns. They disputed with great skill and energy every position which could be defended, and the British advance during the day, though steady, was necessarily slow. Every hamlet, hedgerow, and stream meant a separate skirmish. The troops continually closed ranks, advanced, extended, and attacked from morning to night, sleeping where they had last fought. There was nothing that could be called a serious engagement, and yet the losses — almost entirely from the Third Division — amounted to 300 for the day, the heaviest sufferers being the 2nd Royal Scots.

On the next day, the 13th, the corps swung round its left so as to develop the turning movement already described. Its front of advance was about eight miles, and it met resistance which made all progress difficult. Again the 8th Brigade, especially the Royal Scots and 4th Middlesex, lost heavily. So desperate was the fighting that the Royal Scots had 400 casualties including 9 officers, and the Middlesex fared little better. The principal fighting, however, fell late in the evening upon the 15th Brigade (Gleichen’s), who were on the right of the line and in touch with the Bethune Canal. The enemy, whose line of resistance had been considerably thickened by the addition of several battalions of Jaeger and part of the Fourteenth Corps, made a spirited counterattack on this portion of the advance. The 1st Bedfords were roughly handled and driven back, with the result that the 1st Dorsets, who were stationed at a bridge over the canal near Givenchy, found their flanks exposed and sustained heavy losses, amounting to 400 men, including Major Roper. Colonel Bols, of the same regiment, enjoyed one crowded hour of glorious life, for he was wounded, captured, and escaped all on the same evening. It was in this action also that Major Vandeleur* was wounded and captured.

[ *Major Vandeleur was the officer who afterwards escaped from Krefeld and brought back with him a shocking account of the German treatment of our prisoners. Though a wounded man, the Major was kicked by the direct command of one German officer, and his overcoat was taken from him in bitter weather by another.]

A section of guns which was involved in the same dilemma as the Dorsets had to be abandoned after every gunner had fallen. The 15th Brigade was compelled to fall back for half a mile and entrench itself for the night. On the left the 7th Brigade (McCracken’s) had some eighty casualties in crossing the Lys, and a detachment of Northumberland Fusiliers, who covered their left flank, came under machine-gun fire, which struck down their adjutant, Captain Herbert, and a number of men. Altogether the losses on this day amounted to about twelve hundred men.

On the 14th the Second Corps continued its slow advance in the same direction. Upon this day the Third Division sustained a grievous loss in the shape of its commander, General Sir Hubert Hamilton, who was standing conversing with the quiet nonchalance which was characteristic of him, when a shell burst above him and a shrapnel bullet struck him on the temple, killing him at once. He was a grand commander, beloved by his men, and destined for the highest had he lived. He was buried that night after dark in a village churchyard. There was an artillery attack by the Germans during the service, and the group of silent officers, weary from the fighting line, who stood with bowed heads round the grave, could hardly hear the words of the chaplain for the whiz and crash of the shells. It was a proper ending for a soldier.

His division was temporarily taken over by General Colin Mackenzie. On this date the 13th Brigade, on the south of the canal, was relieved by French troops, so that henceforward all the British were to the north. For the three preceding days this brigade had done heavy work, the pressure of the enemy falling particularly upon the 2nd Scottish Borderers, who lost Major Allen and a number of other officers and men.