Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) (749 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) Online

Authors: NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

e

Julian Hawthorne (1846–1934) was a writer and journalist, as well as the son of Nathaniel Hawthorne. He wrote numerous poems, novels, short stories, essays, travel books, biographies and histories. As a journalist he reported on the Indian Famine for Cosmopolitan magazine, and the Spanish-American War for the New York Journal.

In 1903 he published this biographical work examining his father’s literary and family life.

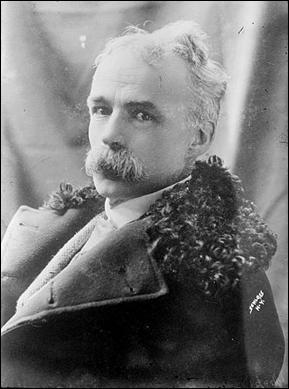

Julian Hawthorne, 1911

Inheritance of friendships — Gracious giants — My own good fortune — My father the central figure — What did his gift to me cost him? — A revelation in Colorado — Privileges make difficulties — Lights and shadows of memory — An informal narrative — Contrast between my father's life and mine.

The best use we can make of good fortune is to share it with our fellows. Those to whom good things come by way of inheritance, however, are often among the latest to comprehend their own advantage; they suppose it to be the common condition. And no doubt I had nearly arrived at man's estate before it occurred to me that the lines of few fishers of men were cast in places so pleasant as mine. I was the son of a man of high desert, who had such friends as he deserved; and these companions and admirers of his gave to me in the beginning of my days a kindly welcome and encouragement generated from their affection and reverence for him. Without doing a stroke of work for it, I found myself early in the enjoyment of a principality of good will and fellowship — a species of freemasonry, I might call it, though the secret was patent enough — for the rights in which, unaided, I might have contended my lifetime long in vain. Men and women whose names are consecrated apart in the dearest thoughts of thousands were familiars and playmates of my childhood; they supported my youth and bade my manhood godspeed. But to me, for a long while, the favor of these gracious giants of mind and character seemed agreeable indeed, but nothing out of the ordinary; my tacit presumption was that other children as well as I could if they would walk hand in hand with Emerson along the village street, seek in the meadows for arrow-heads with Thoreau, watch Powers thump the brown clay of the “Greek Slave,” or listen to the voice of Charlotte Cushman, which could sway assembled thousands, modulate itself to tell stories to the urchin who leaned, rapt, against her knees. Were human felicity so omnipresent as a happy child imagines it, what a world would this be!

In time, my misapprehension was corrected, rather, I think, through the application to it of cold logic than by any rude awakening. I learned of my riches not by losing them — the giants did not withdraw their graciousness — but by comparing the lot of others with my own. And yet, to tell the truth — perhaps I might better leave it untold; only in these chapters, especially, I will not begin with reserves — to say truth, then, my world, during my father's lifetime, and afterwards for I will not say how long, was divided into two natural parts, my father being one of them, and everybody else the other. Hence I was led to regard the parties of the latter part, rich or poor, giants or pygmies, as being, after all, of much the same stature and value. The brightness (in the boy's estimation) of the paternal figure rendered distinctions between other brightnesses unimportant. The upshot was, in short, that I inclined to the opinion that while compassion was unquestionably due to other children for not having a father like mine, yet in other respects my condition was not egregiously superior to theirs. They might not know the Brownings or the Julia Ward Howes; but then, very likely, the Smiths and the Joneses, whom they did know, were nearly as good.

After fifty years, of course, such prepossessions yield to experience. My father was the best friend I ever had, and he will always stand in my estimation distinct from all other friends and persons; but I can now recognize that in addition to the immeasurable debt I owe him for being to me what he was in his own person, he bestowed upon me a privilege also immeasurable in the hospitality of these shining ones who were his intimates. Did the gift cost him nothing? Nothing, in one sense. But, again, what does it cost a man to walk upright and cleanly during the years of his pilgrimage: to deal justly with all, and charitably: diligently to cultivate and develop every natural endowment: always to seek truth, tell it, and vindicate it: to discharge to the utmost of his ability every duty that was intrusted to him: to rest content, in the line of his calling, with no work inferior to his best: to say no word and do no act which, were they known, might weaken the struggle against temptation of any fellow-creature? These qualities were the price at which Hawthorne bought his friends; and in receiving those friends from him, his children could not but feel that the bequest represented his unfaltering grasp upon whatever is pure, lofty, and generous in human life.

Yes, whatever it may cost a man of genius to be all his life a good man, and to use and develop his genius to the noblest ends only, that my father's friends cost him, and in that amount am I his debtor; and the longer I myself live, and the more I see of other men, the higher and rarer do I esteem the obligation. Moreover, in speaking of his friends, I was thinking of those who personally knew him; but the world is full to-day of friends of his who never saw him, to whom his name is my best and surest introduction. Once, only three years since, in the remote heart of the Colorado mountains, I chanced to enter the hut of an aged miner; he sat in a corner of the little family room; on the wall near his hand was fixed a small bookshelf, filled with a dozen dog-eared volumes. The man had for years been paralyzed; he could do little more than to raise to that book-shelf his trembling hand, and take from it one or other of the volumes. When this helpless veteran learned my name, he uttered a strange cry, and his face worked with eager emotion; the wife of his broad-shouldered son brought me to him in his corner; his old eyes glowed as they perused me. I could not gather the meaning of his broken, trembling speech; the young woman interpreted for me. Was I related to the great Hawthorne? “Yes; I am his son.” “His son!” Seldom have I met a gaze harder to sustain than that which the paralytic bent upon me. Would I might have worn, for the time being, the countenance of an archangel, so to fill out the lineaments, drawn during so many lonely years by his imagination and his reverence, of his ideal writer! “The son of Hawthorne!” He said no more, save by the strengthless pressure of his hands upon my own; the woman told me how all the books on the little shelf were my father's books, and for fifteen years the old man had read no others. Helpless tears of joy, of gratitude, of wonder ran down the furrows of his cheeks into his white beard. And how could I at whom he so gazed help being moved: on that desolate, unknown mountain-side, far from the world, the name which I had inherited was loved and honored! One does not get one's privileges for nothing. My father gave me power to make my way, and cast sunshine on the path; but he made the path arduous, too!

Be that as it may, I now ask who will to look in my mirror, and see reflected there some of the figures and the scenes that have made my life worth living. As I peer into the dark abysm of things gone by, many places that seemed at first indistinct, grow clearer; but many more must remain impenetrable. Upon the whole, however, I am surprised to find how much is still discernible. Nearly a score of years ago I published, in the shape of a formal biography of Hawthorne and his wife, the consecutive facts of their lives, and numerous passages from their journals and correspondence. My aim is different now; I wish to indite an informal narrative from my own point of view, as child, youth, and man. There will be gaps in it — involuntary ones; and others occasioned by the obligation to retain those pictures only that seem likely to arouse a catholic interest. Yet there will be a certain intimacy in the story; and some matters which history would omit as trivial will be here adduced, for the sake of such color and character as they may contain. I shall not stalk on stilts, or mouth phrases, but converse comfortably and trustfully as between friends. If a writing of this kind be not flexible, unpretending, discursive, it has no right to be at all. Art is not in question, save the minor art that lives from line to line. Gossip about men, women, and things — it can amount to little more than that.

In the earlier chapters the dramatis personae and the incidents must naturally group themselves about the figure of my father; for it was thus that I saw them. To his boy he was the fountain of love, honor, and energy; and to the boy he seemed the animating or organizing principle of other persons and events. With his death, in my eighteenth year, the world appeared disordered for a season; then, gradually, I learned to do my own orientation. I was destined to an experience superficially much more active and varied than his had been; and it was a world superficially very different from his in which I moved and dealt There must follow a corresponding modification in the character of the narrative; yet that, after all is superficial, too. For the memory of my father has always been with me, and has doubtless influenced me more than I am myself aware. And certainly but for him this book would never have been attempted.