Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) (387 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) Online

Authors: NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

“I am old Philemon!” murmured the oak.

“I am old Baucis!” murmured the linden-tree.

But, as the breeze grew stronger, the trees both spoke at once, — ”Philemon! Baucis! Baucis! Philemon!” — as if one were both and both were one, and talking together in the depths of their mutual heart. It was plain enough to perceive that the good old couple had renewed their age, and were now to spend a quiet and delightful hundred years or so, Philemon as an oak, and Baucis as a linden-tree. And oh, what a hospitable shade did they fling around them. Whenever a wayfarer paused beneath it, he heard a pleasant whisper of the leaves above his head, and wondered how the sound should so much resemble words like these: —

“Welcome, welcome, dear traveler, welcome!”

And some kind soul, that knew what would have pleased old Baucis and old Philemon best, built a circular seat around both their trunks, where, for a great while afterwards, the weary, and the hungry, and the thirsty used to repose themselves, and quaff milk abundantly out of the miraculous pitcher.

And I wish, for all our sakes, that we had the pitcher here now!

“HOW much did the pitcher hold?” asked Sweet Fern.

“It did not hold quite a quart,” answered the student; “but you might keep pouring milk out of it, till you should fill a hogshead, if you pleased. The truth is, it would run on forever, and not be dry even at midsummer, — which is more than can be said of yonder rill, that goes babbling down the hill-side.”

“And what has become of the pitcher now?” inquired the little boy.

“It was broken, I am sorry to say, about twenty-five thousand years ago,” replied Cousin Eustace. “The people mended it as well as they could, but, though it would hold milk pretty well, it was never afterwards known to fill itself of its own accord. So, you see, it was no better than any other cracked earthen pitcher.”

“What a pity!” cried all the children at once.

The respectable dog Ben had accompanied the party, as did likewise a half-grown Newfoundland puppy, who went by the name of Bruin, because he was just as black as a bear. Ben, being elderly, and of very circumspect habits, was respectfully requested, by Cousin Eustace, to stay behind with the four little children, in order to keep them out of mischief. As for black Bruin, who was himself nothing but a child, the student thought it best to take him along, lest, in his rude play with the other children, he should trip them up, and send them rolling and tumbling down the hill. Advising Cowslip, Sweet Fern, Dandelion, and Squash-Blossom to sit pretty still, in the spot where he left them, the student, with Primrose and the elder children, began to ascend, and were soon out of sight among the trees.

INTRODUCTORY TOTHE CHIMÆRA

UPWARD, along the steep and wooded hill-side, went Eustace Bright and his companions. The trees were not yet in full leaf, but had budded forth sufficiently to throw an airy shadow, while the sunshine filled them with green light. There were moss-grown rocks, half hidden among the old, brown, fallen leaves; there were rotten tree-trunks, lying at full length where they had long ago fallen; there were decayed boughs, that had been shaken down by the wintry gales, and were scattered everywhere about. But still, though these things looked so aged, the aspect of the wood was that of the newest life; for, whichever way you turned your eyes, something fresh and green was springing forth, so as to be ready for the summer.

At last, the young people reached the upper verge of the wood, and found themselves almost at the summit of the hill. It was not a peak, nor a great round ball, but a pretty wide plain, or table-land, with a house and barn upon it, at some distance. That house was the home of a solitary family; and oftentimes the clouds, whence fell the rain, and whence the snow-storm drifted down into the valley, hung lower than this bleak and lonely dwelling-place.

On the highest point of the hill was a heap of stones, in the centre of which was stuck a long pole, with a little flag fluttering at the end of it. Eustace led the children thither, and bade them look around, and see how large a tract of our beautiful world they could take in at a glance. And their eyes grew wider as they looked.

Monument Mountain, to the southward, was still in the centre of the scene, but seemed to have sunk and subsided, so that it was now but an undistinguished member of a large family of hills. Beyond it, the Taconic range looked higher and bulkier than before. Our pretty lake was seen, with all its little bays and inlets; and not that alone, but two or three new lakes were opening their blue eyes to the sun. Several white villages, each with its steeple, were scattered about in the distance. There were so many farm-houses, with their acres of woodland, pasture, mowing-fields, and tillage, that the children could hardly make room in their minds to receive all these different objects. There, too, was Tanglewood, which they had hitherto thought such an important apex of the world. It now occupied so small a space, that they gazed far beyond it, and on either side, and searched a good while with all their eyes, before discovering whereabout it stood.

White, fleecy clouds were hanging in the air, and threw the dark spots of their shadow here and there over the landscape. But, by and by, the sunshine was where the shadow had been, and the shadow was somewhere else.

Far to the westward was a range of blue mountains, which Eustace Bright told the children were the Catskills. Among those misty hills, he said, was a spot where some old Dutchmen were playing an everlasting game of nine-pins, and where an idle fellow, whose name was Rip Van Winkle, had fallen asleep, and slept twenty years at a stretch. The children eagerly besought Eustace to tell them all about this wonderful affair. But the student replied that the story had been told once already, and better than it ever could be told again; and that nobody would have a right to alter a word of it, until it should have grown as old as “The Gorgon's Head,” and “The Three Golden Apples,” and the rest of those miraculous legends.

“At least,” said Periwinkle, “while we rest ourselves here, and are looking about us, you can tell us another of your own stories.”

“Yes, Cousin Eustace,” cried Primrose, “I advise you to tell us a story here. Take some lofty subject or other, and see if your imagination will not come up to it. Perhaps the mountain air may make you poetical, for once. And no matter how strange and wonderful the story may be, now that we are up among the clouds, we can believe anything.”

“Can you believe,” asked Eustace, “that there was once a winged horse?”

“Yes,” said saucy Primrose; “but I am afraid you will never be able to catch him.”

“For that matter, Primrose,” rejoined the student, “I might possibly catch Pegasus, and get upon his back, too, as well as a dozen other fellows that I know of. At any rate, here is a story about him; and, of all places in the world, it ought certainly to be told upon a mountain-top.”

So, sitting on the pile of stones, while the children clustered themselves at its base, Eustace fixed his eyes on a white cloud that was sailing by, and began as follows.

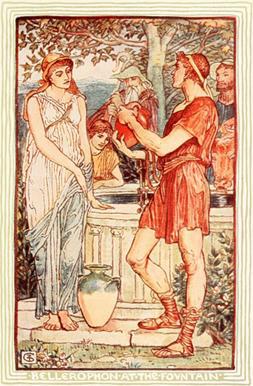

ONCE, in the old, old times (for all the strange things which I tell you about happened long before anybody can remember), a fountain gushed out of a hill-side, in the marvelous land of Greece. And, for aught I know, after so many thousand years, it is still gushing out of the very selfsame spot. At any rate, there was the pleasant fountain, welling freshly forth and sparkling adown the hill-side, in the golden sunset, when a handsome young man named Bellerophon drew near its margin. In his hand he held a bridle, studded with brilliant gems, and adorned with a golden bit. Seeing an old man, and another of middle age, and a little boy, near the fountain, and likewise a maiden, who was dipping up some of the water in a pitcher, he paused, and begged that he might refresh himself with a draught.

“This is very delicious water,” he said to the maiden as he rinsed and filled her pitcher, after drinking out of it. “Will you be kind enough to tell me whether the fountain has any name?”

“Yes; it is called the Fountain of Pirene,” answered the maiden; and then she added, “My grandmother has told me that this clear fountain was once a beautiful woman; and when her son was killed by the arrows of the huntress Diana, she melted all away into tears. And so the water, which you find so cool and sweet, is the sorrow of that poor mother's heart!”

“I should not have dreamed,” observed the young stranger, “that so clear a well-spring, with its gush and gurgle, and its cheery dance out of the shade into the sunlight, had so much as one tear-drop in its bosom! And this, then, is Pirene? I thank you, pretty maiden, for telling me its name. I have come from a far-away country to find this very spot.”

A middle-aged country fellow (he had driven his cow to drink out of the spring) stared hard at young Bellerophon, and at the handsome bridle which he carried in his hand.

“The water-courses must be getting low, friend, in your part of the world,” remarked he, “if you come so far only to find the Fountain of Pirene. But, pray, have you lost a horse? I see you carry the bridle in your hand; and a very pretty one it is with that double row of bright stones upon it. If the horse was as fine as the bridle, you are much to be pitied for losing him.”

“I have lost no horse,” said Bellerophon, with a smile. “But I happen to be seeking a very famous one, which, as wise people have informed me, must be found hereabouts, if anywhere. Do you know whether the winged horse Pegasus still haunts the Fountain of Pirene, as he used to do in your forefathers' days?”

But then the country fellow laughed.

Some of you, my little friends, have probably heard that this Pegasus was a snow-white steed, with beautiful silvery wings, who spent most of his time on the summit of Mount Helicon. He was as wild, and as swift, and as buoyant, in his flight through the air, as any eagle that ever soared into the clouds. There was nothing else like him in the world. He had no mate; he never had been backed or bridled by a master; and, for many a long year, he led a solitary and a happy life.

Oh, how fine a thing it is to be a winged horse! Sleeping at night, as he did, on a lofty mountain-top, and passing the greater part of the day in the air, Pegasus seemed hardly to be a creature of the earth. Whenever he was seen, up very high above people's heads, with the sunshine on his silvery wings, you would have thought that he belonged to the sky, and that, skimming a little too low, he had got astray among our mists and vapors, and was seeking his way back again. It was very pretty to behold him plunge into the fleecy bosom of a bright cloud, and be lost in it, for a moment or two, and then break forth from the other side. Or, in a sullen rain-storm, when there was a gray pavement of clouds over the whole sky, it would sometimes happen that the winged horse descended right through it, and the glad light of the upper region would gleam after him. In another instant, it is true, both Pegasus and the pleasant light would be gone away together. But any one that was fortunate enough to see this wondrous spectacle felt cheerful the whole day afterwards, and as much longer as the storm lasted.

In the summer-time, and in the beautifullest of weather, Pegasus often alighted on the solid earth, and, closing his silvery wings, would gallop over hill and dale for pastime, as fleetly as the wind. Oftener than in any other place, he had been seen near the Fountain of Pirene, drinking the delicious water, or rolling himself upon the soft grass of the margin. Sometimes, too (but Pegasus was very dainty in his food), he would crop a few of the clover-blossoms that happened to be sweetest.

To the Fountain of Pirene, therefore, people's great-grandfathers had been in the habit of going (as long as they were youthful, and retained their faith in winged horses), in hopes of getting a glimpse at the beautiful Pegasus. But, of late years, he had been very seldom seen. Indeed, there were many of the country folks, dwelling within half an hour's walk of the fountain, who had never beheld Pegasus, and did not believe that there was any such creature in existence. The country fellow to whom Bellerophon was speaking chanced to be one of those incredulous persons.

And that was the reason why he laughed.

“Pegasus, indeed!” cried he, turning up his nose as high as such a flat nose could be turned up, — ”Pegasus, indeed! A winged horse, truly! Why, friend, are you in your senses? Of what use would wings be to a horse? Could he drag the plow so well, think you? To be sure, there might be a little saving in the expense of shoes; but then, how would a man like to see his horse flying out of the stable window? — yes, or whisking up him above the clouds, when he only wanted to ride to mill? No, no! I don't believe in Pegasus. There never was such a ridiculous kind of a horse-fowl made!”

“I have some reason to think otherwise,” said Bellerophon, quietly.

And then he turned to an old, gray man, who was leaning on a staff, and listening very attentively, with his head stretched forward, and one hand at his ear, because, for the last twenty years, he had been getting rather deaf.

“And what say you, venerable sir?” inquired he. “In your younger days, I should imagine, you must frequently have seen the winged steed!”

“Ah, young stranger, my memory is very poor!” said the aged man. “When I was a lad, if I remember rightly, I used to believe there was such a horse, and so did everybody else. But, nowadays, I hardly know what to think, and very seldom think about the winged horse at all. If I ever saw the creature, it was a long, long while ago; and, to tell you the truth, I doubt whether I ever did see him. One day, to be sure, when I was quite a youth, I remember seeing some hoof-tramps round about the brink of the fountain. Pegasus might have made those hoof-marks; and so might some other horse.”

“And have you never seen him, my fair maiden?” asked Bellerophon of the girl, who stood with the pitcher on her head, while this talk went on. “You certainly could see Pegasus, if anybody can, for your eyes are very bright.”

“Once I thought I saw him,” replied the maiden, with a smile and a blush. “It was either Pegasus, or a large white bird, a very great way up in the air. And one other time, as I was coming to the fountain with my pitcher, I heard a neigh. Oh, such a brisk and melodious neigh as that was! My very heart leaped with delight at the sound. But it startled me, nevertheless; so that I ran home without filling my pitcher.”

“That was truly a pity!” said Bellerophon.

And he turned to the child, whom I mentioned at the beginning of the story, and who was gazing at him, as children are apt to gaze at strangers, with his rosy mouth wide open.

“Well, my little fellow,” cried Bellerophon, playfully pulling one of his curls, “I suppose you have often seen the winged horse.”

“That I have,” answered the child, very readily. “I saw him yesterday, and many times before.”

“You are a fine little man!” said Bellerophon, drawing the child closer to him. “Come, tell me all about it.”

“Why,” replied the child, “I often come here to sail little boats in the fountain, and to gather pretty pebbles out of its basin. And sometimes, when I look down into the water, I see the image of the winged horse, in the picture of the sky that is there. I wish he would come down, and take me on his back, and let me ride him up to the moon! But, if I so much as stir to look at him, he flies far away out of sight.”

And Bellerophon put his faith in the child, who had seen the image of Pegasus in the water, and in the maiden, who had heard him neigh so melodiously, rather than in the middle-aged clown, who believed only in cart-horses, or in the old man who had forgotten the beautiful things of his youth.

Therefore, he haunted about the Fountain of Pirene for a great many days afterwards. He kept continually on the watch, looking upward at the sky, or else down into the water, hoping forever that he should see either the reflected image of the winged horse, or the marvelous reality. He held the bridle, with its bright gems and golden bit, always ready in his hand. The rustic people, who dwelt in the neighborhood, and drove their cattle to the fountain to drink, would often laugh at poor Bellerophon, and sometimes take him pretty severely to task. They told him that an able-bodied young man, like himself, ought to have better business than to be wasting his time in such an idle pursuit. They offered to sell him a horse, if he wanted one; and when Bellerophon declined the purchase, they tried to drive a bargain with him for his fine bridle.

Even the country boys thought him so very foolish, that they used to have a great deal of sport about him, and were rude enough not to care a fig, although Bellerophon saw and heard it. One little urchin, for example, would play Pegasus, and cut the oddest imaginable capers, by way of flying; while one of his schoolfellows would scamper after him, holding forth a twist of bulrushes, which was intended to represent Bellerophon's ornamental bridle. But the gentle child, who had seen the picture of Pegasus in the water, comforted the young stranger more than all the naughty boys could torment him. The dear little fellow, in his play-hours, often sat down beside him, and, without speaking a word, would look down into the fountain and up towards the sky, with so innocent a faith, that Bellerophon could not help feeling encouraged.

Now you will, perhaps, wish to be told why it was that Bellerophon had undertaken to catch the winged horse. And we shall find no better opportunity to speak about this matter than while he is waiting for Pegasus to appear.

If I were to relate the whole of Bellerophon's previous adventures, they might easily grow into a very long story. It will be quite enough to say, that, in a certain country of Asia, a terrible monster, called a Chimæra, had made its appearance, and was doing more mischief than could be talked about between now and sunset. According to the best accounts which I have been able to obtain, this Chimæra was nearly, if not quite, the ugliest and most poisonous creature, and the strangest and unaccountablest, and the hardest to fight with, and the most difficult to run away from, that ever came out of the earth's inside. It had a tail like a boa-constrictor; its body was like I do not care what; and it had three separate heads, one of which was a lion's, the second a goat's, and the third an abominably great snake's. And a hot blast of fire came flaming out of each of its three mouths! Being an earthly monster, I doubt whether it had any wings; but, wings or no, it ran like a goat and a lion, and wriggled along like a serpent, and thus contrived to make about as much speed as all the three together.