Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (219 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

Such are the plain facts of the case, out of which it must, doubtless, to the healthy, charitable mind appear impossible that calumny could spring.

But it has.

Persons — I say ‘persons’ — have professed themselves unable to understand the simple circumstances herein narrated, except in the light of explanations at once misleading and insulting. Slurs have been cast and aspersions made on me by those of my own flesh and blood.

But I bear no ill-feeling. I merely, as I have said, set forth this statement for the purpose of clearing my character from injurious suspicion.

JOHN INGERFIELD AND OTHER STORIES

First published in 1893, this is a collection of stories that Jerome had originally composed for the periodical press. By this point, Jerome was becoming tired of being constantly seen as a writer purely of humorous stories — so much so that he felt moved to write a note to readers insisting that the at least three of the stories in this collection (“John Ingerfield”, “The Woman of the Sæter” and “Silhouettes”) were most emphatically not intended as comedies and were to be taken as seriously as any author’s work. Readers of these stories surely need no such warning, as they encounter grim and tragic subject matter, including financial ruin, unhappy marriages and untimely death, all of which are effectively and memorably portrayed.

The first edition

CONTENTS

IN REMEMBRANCE OF JOHN INGERFIELD, AND OF ANNE, HIS WIFE A STORY OF OLD LONDON, IN TWO CHAPTERS

THE LEASE OF THE “CROSS KEYS.”

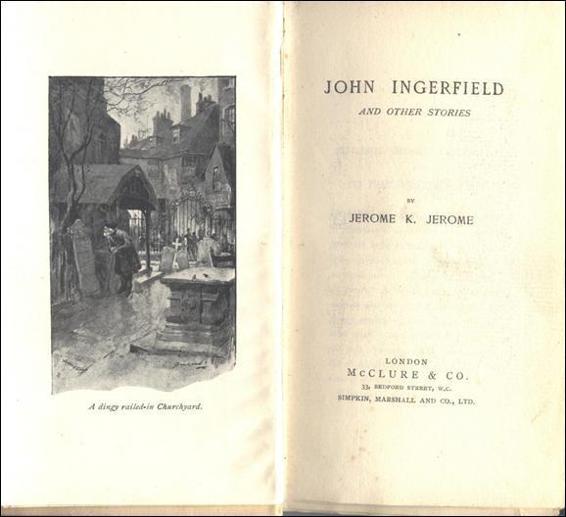

Title page of the first edition

TO THE GENTLE READER; also TO THE GENTLE CRITIC.

Once upon a time, I wrote a little story of a woman who was crushed to death by a python. A day or two after its publication, a friend stopped me in the street. “Charming little story of yours,” he said, “that about the woman and the snake; but it’s not as funny as some of your things!” The next week, a newspaper, referring to the tale, remarked, “We have heard the incident related before with infinitely greater humour.”

With this — and many similar experiences — in mind, I wish distinctly to state that “John Ingerfield,” “The Woman of the Sæter,” and “Silhouettes,” are not intended to be amusing. The two other items—”Variety Patter,” and “The Lease of the Cross Keys” — I give over to the critics of the new humour to rend as they will; but “John Ingerfield,” “The Woman of the Sæter,” and “Silhouettes,” I repeat, I should be glad if they would judge from some other standpoint than that of humour, new or old.

IN REMEMBRANCE OF JOHN INGERFIELD

AND OF ANNE, HIS WIFE A STORY OF OLD LONDON, IN TWO CHAPTERS

CHAPTER I.

If you take the Underground Railway to Whitechapel Road (the East station), and from there take one of the yellow tramcars that start from that point, and go down the Commercial Road, past the George, in front of which starts — or used to stand — a high flagstaff, at the base of which sits — or used to sit — an elderly female purveyor of pigs’ trotters at three-ha’pence apiece, until you come to where a railway arch crosses the road obliquely, and there get down and turn to the right up a narrow, noisy street leading to the river, and then to the right again up a still narrower street, which you may know by its having a public-house at one corner (as is in the nature of things) and a marine store-dealer’s at the other, outside which strangely stiff and unaccommodating garments of gigantic size flutter ghost-like in the wind, you will come to a dingy railed-in churchyard, surrounded on all sides by cheerless, many-peopled houses. Sad-looking little old houses they are, in spite of the tumult of life about their ever open doors. They and the ancient church in their midst seem weary of the ceaseless jangle around them. Perhaps, standing there for so many years, listening to the long silence of the dead, the fretful voices of the living sound foolish in their ears.

Peering through the railings on the side nearest the river, you will see beneath the shadow of the soot-grimed church’s soot-grimed porch — that is, if the sun happen, by rare chance, to be strong enough to cast any shadow at all in that region of grey light — a curiously high and narrow headstone that once was white and straight, not tottering and bent with age as it is now. There is upon this stone a carving in bas-relief, as you will see for yourself if you will make your way to it through the gateway on the opposite side of the square. It represents, so far as can be made out, for it is much worn by time and dirt, a figure lying on the ground with another figure bending over it, while at a little distance stands a third object. But this last is so indistinct that it might be almost anything, from an angel to a post.

And below the carving are the words (already half obliterated) that I have used for the title of this story.

Should you ever wander of a Sunday morning within sound of the cracked bell that calls a few habit-bound, old-fashioned folk to worship within those damp-stained walls, and drop into talk with the old men who on such days sometimes sit, each in his brass-buttoned long brown coat, upon the low stone coping underneath those broken railings, you might hear this tale from them, as I did, more years ago than I care to recollect.

But lest you do not choose to go to all this trouble, or lest the old men who could tell it you have grown tired of all talk, and are not to be roused ever again into the telling of tales, and you yet wish for the story, I will here set it down for you.

But I cannot recount it to you as they told it to me, for to me it was only a tale that I heard and remembered, thinking to tell it again for profit, while to them it was a thing that had been, and the threads of it were interwoven with the woof of their own life. As they talked, faces that I did not see passed by among the crowd and turned and looked at them, and voices that I did not hear spoke to them below the clamour of the street, so that through their thin piping voices there quivered the deep music of life and death, and my tale must be to theirs but as a gossip’s chatter to the story of him whose breast has felt the press of battle.

* * * * *

John Ingerfield, oil and tallow refiner, of Lavender Wharf, Limehouse, comes of a hard-headed, hard-fisted stock. The first of the race that the eye of Record, piercing the deepening mists upon the centuries behind her, is able to discern with any clearness is a long-haired, sea-bronzed personage, whom men call variously Inge or Unger. Out of the wild North Sea he has come. Record observes him, one of a small, fierce group, standing on the sands of desolate Northumbria, staring landward, his worldly wealth upon his back. This consists of a two-handed battle-axe, value perhaps some forty stycas in the currency of the time. A careful man, with business capabilities, may, however, manipulate a small capital to great advantage. In what would appear, to those accustomed to our slow modern methods, an incredibly short space of time, Inge’s two-handed battle-axe has developed into wide lands and many head of cattle; which latter continue to multiply with a rapidity beyond the dreams of present-day breeders. Inge’s descendants would seem to have inherited the genius of their ancestor, for they prosper and their worldly goods increase. They are a money-making race. In all times, out of all things, by all means, they make money. They fight for money, marry for money, live for money, are ready to die for money.

In the days when the most saleable and the highest priced article in the markets of Europe was a strong arm and a cool head, then each Ingerfield (as “Inge,” long rooted in Yorkshire soil, had grown or been corrupted to) was a soldier of fortune, and offered his strong arm and his cool head to the highest bidder. They fought for their price, and they took good care that they obtained their price; but, the price settled, they fought well, for they were staunch men and true, according to their lights, though these lights may have been placed somewhat low down, near the earth.

Then followed the days when the chief riches of the world lay tossed for daring hands to grasp upon the bosom of the sea, and the sleeping spirit of the old Norse Rover stirred in their veins, and the lilt of a wild sea-song they had never heard kept ringing in their ears; and they built them ships and sailed for the Spanish Main, and won much wealth, as was their wont.

Later on, when Civilisation began to lay down and enforce sterner rules for the game of life, and peaceful methods promised to prove more profitable than violent, the Ingerfields became traders and merchants of grave mien and sober life; for their ambition from generation to generation remains ever the same, their various callings being but means to an end.

A hard, stern race of men they would seem to have been, but just — so far as they understood justice. They have the reputation of having been good husbands, fathers, and masters; but one cannot help thinking of them as more respected than loved.

They were men to exact the uttermost farthing due to them, yet not without a sense of the thing due from them, their own duty and responsibility — nay, not altogether without their moments of heroism, which is the duty of great men. History relates how a certain Captain Ingerfield, returning with much treasure from the West Indies — how acquired it were, perhaps, best not to inquire too closely — is overhauled upon the high seas by King’s frigate. Captain of King’s frigate sends polite message to Captain Ingerfield requesting him to be so kind as to promptly hand over a certain member of his ship’s company, who, by some means or another, has made himself objectionable to King’s friends, in order that he (the said objectionable person) may be forthwith hanged from the yard-arm.

Captain Ingerfield returns polite answer to Captain of King’s frigate that he (Captain Ingerfield) will, with much pleasure, hang any member of his ship’s company that needs hanging, but that neither the King of England nor any one else on God Almighty’s sea is going to do it for him. Captain of King’s frigate sends back word that if objectionable person be not at once given up he shall be compelled with much regret to send Ingerfield and his ship to the bottom of the Atlantic. Replies Captain Ingerfield, “That is just what he will have to do before I give up one of my people,” and fights the big frigate — fights it so fiercely that after three hours Captain of King’s frigate thinks it will be good to try argument again, and sends therefore a further message, courteously acknowledging Captain Ingerfield’s courage and skill, and suggesting that, he having done sufficient to vindicate his honour and renown, it would be politic to now hand over the unimportant cause of contention, and so escape with his treasure.

“Tell your Captain,” shouts back this Ingerfield, who has discovered there are sweeter things to fight for than even money, “that the

Wild Goose

has flown the seas with her belly full of treasure before now, and will, if it be God’s pleasure, so do again, but that master and man in her sail together, fight together, and die together.”