Delphi (11 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

So just what was it like to visit Delphi during this period? We left the sanctuary in the late eighth century as a place of significant settlement, having recently suffered fire destruction, and yet with increasing numbers of expensive metal (particularly) tripod dedications associated with cult activity arriving from a widening circle of Greek communities as far away as Crete. During the seventh century, the site continued as a place of settlement, mixed in with increasing cult activity. Over the burned remains of the maison noire, the

maison jaune

(the “yellow house”) was constructed. By the last quarter of the seventh century, this was replaced by the

maison rouge

(the “red house”) which seems to have been one of several in the area. This house was comprised of three rooms, one of which was used for cooking. The nature of the finds suggests a wealthy owner (bronze vessels, golden rivets for some objects), but also cult activity (libation

phiale

[small vessels] have been found).

43

This house sat across what was later the boundary of the Apollo sanctuary, and its mixed sacred and secular use seems to sum up the indeterminate, unarticulated nature of what scholars presume was an early sacred area at the heart of the settlement that would later become the Apollo sanctuary.

As such, the settlement at Delphi, right through to the end of the seventh century

BC

(the house was not destroyed until the first quarter of the sixth century), seems to have been a melting pot of secular and sacred activity, with no properly defined or separated cult space (there is no evidence for a temenos wall marking out a sanctuary until the sixth centuryâsee the next chapter). As Delphi's oracle continued to grow in importance through the century, even allowing for much of that early

reputation only having been generated in later centuries, consultants and dedicators, on making their way up the Parnassian mountainside to Delphi, may well have been surprised to find such an unelaborated cult site for such an (increasingly) important institution, especially in comparison with the many sanctuaries in different cities and civic territories, which had been monumentalized from the late eighth century onward (e.g., at Corinth, Perachora, and Argos, and on Samos).

This lack of monumental elaboration, even articulation, of Delphi's sacred space through the seventh century is a crucial marker of three things. First, it underscores the importance of handling the literary sources with care to work out what Delphi was, as opposed to what it was later constructed to have been. Second, it reveals an important insight into the experience of early visitors to the site, especially in contrast to the sanctuaries at home. Third, it acts as crucial evidence for the generally late elaboration of sanctuaries, which would eventually become “Panhellenic”âsanctuaries common to all Greeks. These sacred spaces were less elaborate than sanctuaries within defined political territories because they were not the sole responsibility and territory of one community. But it was also precisely because of their indeterminacy of ownership, their “neutrality,” that scholars argue they were

able

to grow as spaces for use by a much wider range of Greek cities and states.

44

This is to say, Delphi's late elaboration was a(nother) sign of its crucial impending significance.

Despite that Delphi could offer little in the way of articulated or monumental sacred architecture through the seventh century (and, as it has been argued, to some extent,

because

it could not), it

was

the recipient of increasing numbers of offerings from number of individuals and cities. We have already seen how Kings Midas, Gyges, and Alyattes from the East were said to have dedicated at Delphi a throne as well as a series of gold, bronze, and iron vessels and objects. Yet what is fascinating is what the dedication of these objects tells us about how different contributors interacted with the sanctuary. As far as we can tell, for example, all the monumental dedications coming from the East (from this period and on into the sixth century) were located on the eastern side of the (later

temple of Apollo), in contrast to most other (monumental) dedications during the seventh and early sixth century, which gravitated toward the West (see

plate 2

). This has been explained as an eastern preference for the East, but also as a continuation of their traditional practice when making dedications at other sanctuaries (that is to say these eastern dedicators did what they were used to doing, without being influenced by what others were doing at Delphi).

45

It was not only Eastern dedications that had their particular traits. During the seventh century

BC

, for example, Corinth does not seem to have continued with its dedication of bronze tripods, but only of pottery and, even then, only in the unelaborated sacred areas of the settlement. There is no Corinthian pottery in the maison rouge, for example, only locally made material.

46

Yet, around the middle of the seventh century, the new tyrant of Corinth, Cypselus (who had been so involved with the oracle), constructed Delphi's first (surviving) monumental dedication: a structure known as a treasury, because we think it was used as a treasure house to store other offerings (see

plate 2

).

47

This treasury, constructed in a highly visible location on a sort of natural crest in the landscape on the steep hillside, facing toward what scholars think was (or at least became) the earliest entryway into the sacred area, would have acted, at a time when Delphi had no official boundary markers, as an early marker of the sacred space. Cypselus, not only fundamental to the story of the oracle, is crucial in the story of the elaboration of Delphi as a sanctuary.

48

In contrast to Corinth, Attica (and, at its heart, Athens) had a slow start at Delphi. Though some Attic bronze offerings can be identified as from the late eighth century, the numbers are low throughout the seventh century when Athenian pottery is nowhere to be seen. But at the very end of the century (and gathering speed from then on), the Athenians seem to have copied Cypselus and constructed a small treasury on the west side of the later sanctuary. Laconia, on the other hand, despite the number of consultations that associate Sparta with the Delphic oracle, was limited in its offerings at the sanctuary throughout the century. And despite the trade routes between Delphi and the North, the number of objects found at the sanctuary from northern and western Greece is also low, especially

when compared with the numbers of Macedonian and Balkan objects found at Olympia, which is, after all, much farther south.

49

Yet other areas of mainland Greece seem better represented. Several Boeotian cauldrons have been found, and a significant supply of armor from the Argolid seems to have been dedicated (though the Argolid does not seem to have offered any vases or terra-cottas). This trend for Argolid dedication was capped at the end of the seventh century

BC

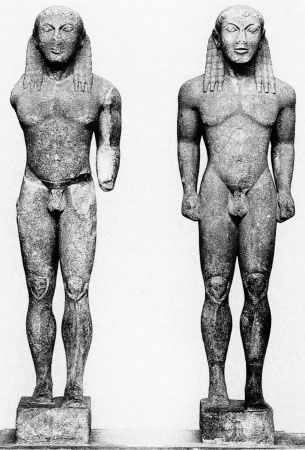

by the dedication of a pair of over-life-size statues, which have often been identified with one of Argos's most famous myths, that of Cleobis and Biton (

fig. 3.1

).

50

Cyprus is also well representedâwith shields, inscribed

tripods, a number of cauldrons, and even a bronze bull.

51

So are Syria and Asia Minor, with lots of complex and beautiful cauldron decorations, ostrich eggs, glass human figurines, and even Phrygian belts (all found in recent excavations).Yet it is Crete that stands out, not only because of the number of tripods and shields, but also because of the way in which these offerings seem to be not isolated pieces but entire sets and series of dedications, and possibly even from the same area.

52

Figure 3.1

. The Argive twins dedicated at Delphi, sometimes identified as Cleobis and Biton or simply as the Dioscuri (© EFA [Guide du Musée fig. 2a])

Delphi, by 600

BC

, may well have still been without a temple, or indeed any articulated, separated, sacred space, but it was, without doubt, already littered with offerings from the very small to the monumental, in a wide array of materials and styles, from a wide variety of dedicators. Once again, however, this material comes with a warning. While we label a piece “Cretan” because it is made in a style, procedure, or material we know to be associated with Crete, we cannot be sure that it was actually offered at the sanctuary by a Cretan, as opposed to its coming to the sanctuary via, say, a Corinthian trading network, or as the treasured possession of someone from outside Crete, or even as a prize dedicated by someone who was victorious over the Cretans in battle and took the piece as a victory trophy. Moreover, even some of the more monumental structures remain a mystery. A small, apsidal treasury-like structure was constructed around 600

BC

in an area that would later be the temple terrace and even later be identified as the sanctuary of Gaia (see structure “B” in

fig. 3.2

). This, combined with its odd (and therefore supposedly religious) absidal-shaped end, as well as the literary myths about Delphi's early association with Gaia, the mother goddess, have led to this structure's often being called the Chapel of Gaia (as well as a possible early home for the omphalos). But in truth, there is not one shred of evidence that definitely connects this structure to Gaia. In reality, we simply have no idea who constructed it and why they did so.

53

What we can do is begin to see increasing variation in the purpose and style with which different individuals, cities, and geographical areas interacted with Delphi in these crucial early phases of development. Not only in terms of their material offerings or trade connections, but by putting these together with the literary evidence for oracular consultation and mythical involvement, we can begin to have a more three-dimensional view of how Delphi was perceived in the wider Greek world, and the different ways in which the different parts of that world chose to interact (and were represented as interacting) with it. What this brings into focus is the way certain communities interacted with particular parts of Delphic cult activity, but not others. The Laconians, for instance, had a close and ongoing relationship with the oracle, but dedicated very few offerings at the sanctuary before the sixth century

BC

. In complete contrast was Crete. Cretans dedicated many expensive smaller offerings (tripods, shields, etc.), but (probably) not a single monumental offering. They did not consult the oracle, unless you count one individual Cretan asking about the omphalos, which is probably a later creation. Yet Crete was fundamentally tied to Delphi from the late seventh century through the

Homeric Hymn to Apollo

as Cretans became the first priests of Apollo's temple.

54

Even more interestingly, no Cretan tripods have been found at Olympia, a sanctuary with which Delphi is often compared, but which, from its earliest history, seems to have attracted something of a different clientele from Delphi and seems to have been a center for different priorities and interests.

55

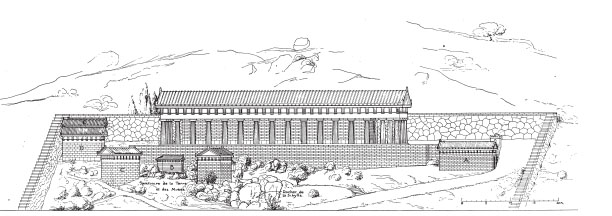

Figure 3.2

. The sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi c. 550

BC

(© EFA [Courby FD II Terrasse du Temple 1920â29 fig. 156]).

Coming into focus also through this three-dimensional approach to early Delphi are the players, and tensions, that would, in the early sixth century

BC

, rip Delphi apart and catapult it forward. The dominant players at Delphi by the end of the seventh century seem to have been Sparta, Corinth, Lydia in the east, and increasingly Attica. Particularly these mainland Greek cities and city-states were users of the oracle, and to different extents, dedicators of cult offerings. In contrast, the longer-term influence of Thessaly on the site is not reflected in Thessalian interest in either of these activities during the seventh century.

56

Instead Delphi was changing, its focus turning from the trade corridor north toward the sea and land routes to the south, just as its livelihood seems to have become more dependent on the oracle and visitors to the sanctuary, who were themselves increasingly from polis city-states rather than older,

ethnos

political groupings (like Thessaly). Delphi itself was an increasingly rich settlement, full of treasures, its wealth now widely recognized and by now most probably the subject of one or more elaborate foundation stories. But, at the same time, Delphi had little architectural elaboration or protection, and was under the auspices of no major city. As the inhabitants of Delphi went about their business at the end of the seventh century, their treasures glistening in the sunlight in among their houses, few may have realized that there was a storm brewing. The great age of state activity in the Greek world was about to begin. Delphi, and its oracle, had, for a number of reasons, been turned into an increasingly crucial instrument in the dynamic and volatile processes of social and political change that Greece was undergoing, at the very moment when those processes were increasingly encouraging its constituents to butt heads. Delphi was a rich and unprotected place that many of these communities had a stake in. Who would try to claim it as their prize, and what would happen to Delphi as a result?