Decoded (34 page)

Authors: Jay-Z

Tags: #Rap & Hip Hop, #Rap musicians, #Rap musicians - United States, #Cultural Heritage, #Jay-Z, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

W

hen I made my first album, it was my intention to make it my last. I threw everything I had into

Reasonable Doubt,

but then the plan was to move in to the corner office and run our label. I didn’t do that. So instead of being a definitive statement that would end with the sound of me dropping the mic forever, it was just the beginning of something. That something was the creation of the character Jay-Z.

Rappers refer to themselves a lot. What the rapper is doing is creating a character that, if you’re lucky, you find out about more and more from song to song. The rapper’s character is essentially a conceit, a first-person literary creation. The core of that character has to match the core of the rapper himself. But then that core gets amplified by the rapper’s creativity and imagination. You can be anybody in the booth. It’s like wearing a mask. It’s an amazing freedom but also a temptation. The temptation is to go too far, to pretend the mask is real and try to convince people that you’re something that you’re not. The best rappers use their imaginations to take their own core stories and emotions and feed them to characters who can be even more dramatic or epic or provocative. And whether it’s in a movie or a television show or whatever, the best characters get inside of us. We care about them. We love them or hate them. And we start to see ourselves in them—in a crazy way, become them.

SCARFACE

THE MOVIE DID MORE THAN SCARFACE THE RAPPER TO ME

In hip-hop, there’s practically a cult built up around the 1983 remake of

Scarface,

the one starring Al Pacino. Lines from that movie are scattered all over hip-hop, including my own songs:

All I got is my balls and my word.

The world is yours.

I always tell the truth, even when I lie.

Don’t get high on your own supply.

You fuck with me, you’re fuckin with the best!

Say goodnight to the bad guy.

Okay! I’m reloaded!

You gotta get the money first. When you get the money, you get the power.

When you get the power, you get the women.

Who do I trust? Me, that’s who!

and of course

Say hello to my little friend!

So many people saw their story in that movie. No one literally looked in the mirror and saw Tony Montana staring back at them. I hope. But there are people who feel Tony’s emotions as if they were their own, feel the words he speaks like they’re coming out of their own mouths.

I’ve always found this a little strange because—I hope I’m not giving anything away here—at the end of the movie, Tony gets shot. He’s wasted. His life is in ruins. His family is destroyed. It’s funny that so many people use the phrase “the world is yours” as a statement of triumph, when in the movie the last time the words occur, they’re underneath Tony’s bloody body in a fountain. But that’s not what people identify with. It seems like the movie ends in some people’s memory about two-thirds of the way through, before it all goes to shit for Tony. And for those two-thirds of the movie, they are Tony. And after the movie, Tony is still alive in them as an inspiration—and maybe a cautionary tale, too, like, Yeah, I’ll be like Tony but not make the same mistakes. The viewer inhabits the character while the movie runs, but when it’s over, the character lives on in the viewer. So instead of passing judgment on Tony, you make a complete empathetic connection to the good and bad in him; you feel a sense of ownership over his character and behavior. That’s how it works with great characters.

HOW YOU RATE MUSIC THAT THUGS WITH NOTHIN RELATE TO IT?

People connect the same way to the character Jay-Z. Like I said, rappers refer to themselves a lot in their music, but it’s not strictly because rappers are immodest. Part of it is about boasting—that’s a big part of what rap is traditionally about. But a lot of the self-reference has nothing to do with bragging or boasting. Rappers are just crafting a character that the listener can relate to. Not every rapper bothers with creating a big first-person character. Chuck D, a great MC, never really makes himself into a larger-than-life character because his focus is on analyzing the larger world from an almost objective, argumentative point of view, even when he’s speaking in a first-person voice. You rarely

become

Chuck D when you’re listening to Public Enemy; it’s more like watching a really, really lively speech. On the other hand, you have MCs like DMX for whom everything comes from a subjective, personal place. When he growls out a line like

on parole with warrants that’ll send me back the raw way

the person rapping along to it in their car is completely living the lyrics, like it’s happening to them. They relate.

When Lauryn Hill came out with

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill,

for a while it was the only thing I listened to. Lauryn is a very different person from me, of course, but I felt her lyrics like they were mine. She was also one of the few contemporary female MCs I could even rap along to in my car. I love Lil’ Kim, but I’d be a little nervous pulling up to a light and having someone see me rapping along to “Queen Bitch.” Lauryn’s lyrics transcended the specifics of gender and personal biography, which is why she connected to so many people with that album. All kinds of people could find themselves in those songs and in the character she created.

MY CORPORATE THUGS BE LIKE, YEAH JIGGA TALK THAT SHIT

There’s a funny Dave Chappelle bit, one of his “When Keeping It Real Goes Wrong” sketches. Chappelle plays a young black guy named Vernon who works as a vice president at a major corporation. At the end of a meeting, a bald white colleague tells him, “Vernon, you da man,” and the Chappelle character snaps. He stands up and gets in the dude’s face. “Allow me to reintroduce myself. My name is Hov!” He ends up working at a gas station. It’s funny, but the truth is I do hear about guys in corporate offices who psych themselves up listening to my music, which sounds odd at first, but makes sense. My friend Steve Stoute, who spends a lot of time in the corporate world, tells me about young execs he knows who say they discovered their own philosophies of business and life in my lyrics. It’s crazy. But when people hear me telling my stories, or boasting in my songs, or whatever, they don’t hear some rapper telling them how much better than them he is. They hear it as their own voice. It taps in to the part of them that needs every now and then to say, Fuck it, allow me to reintroduce myself, nigga. And when I’m really talking shit, like in this piece from the song “Threats” off

The Black Album

—

Put that knife in ya, take a little bit of life from ya

Am I frightenin ya? Shall I continue?

I put the gun to ya, I let it sing you a song

I let it hum to ya, the other one sing along

Now it’s a duet, and you wet, when you check out

the technique from the 2 tecs and I don’t need two lips

To blow this like a trumpet you dumb shit

I don’t think any listeners think I’m threatening them. I think they’re singing along with me, threatening someone else. They’re thinking,

Yeah, I’m coming for you.

And they might apply it to anything, to taking their next math test or straightening out that chick talking outta pocket in the next cubicle. When it seems like I’m bragging or threatening or whatever, what I’m actually trying to do is to embody a certain spirit, give voice to a certain emotion. I’m giving the listener a way to articulate that emotion in their own lives, however it applies. Even when I do a song that feels like a complete autobiography, like “December 4th,” I’m still trying to speak to something that everyone can find in themselves.

I’LL TELL YOU HALF THE STORY, THE REST YOU FILL IT IN

Of course,

Reasonable Doubt

wasn’t my only album. But as I was moving into my early thirties, I wanted to challenge myself in new ways. I was looking forward to building a label from the ground up, starting from scratch. Roc-A-Fella’s deal with Def Jam was set to expire and I saw it as the perfect time to move on. When I announced plans to begin recording

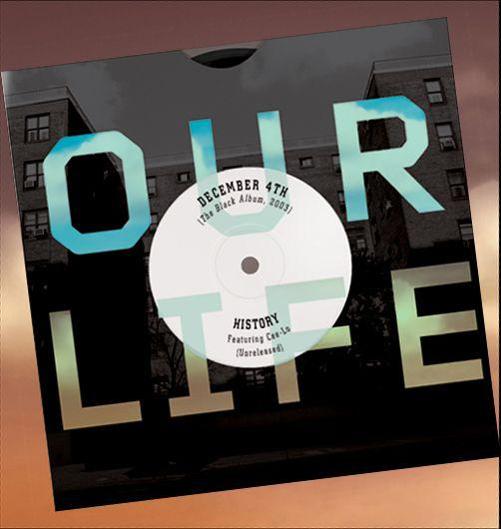

The Black Album,

I said it would be my last for at least two years, and that story grew into rumors about retirement. I considered an all-out retirement out loud to the media, and that was a mistake even though I definitely gave the idea a lot of space in my head.

When I first started planning

The Black Album,

it was a concept album. I wanted to do what Prince had done, release an album of my most personal autobiographical tracks with absolutely no promotion. No cover art, no magazine ads, no commercials, nothing; one day the album would just appear on the shelves and the buzz would build organically.

Like my dream of

Reasonable Doubt

being my only album, that idea quickly evaporated. But I stuck to the idea of making the album more explicitly autobiographical than anything I’d done before. “December 4th,” the song that opens the album, is itself a capsule autobiography. I took my mother out for her birthday and on the way to the restaurant I made her take a detour to Bassline and tell some stories about my life. These were stories that were already legend in my family; I’d heard them all a million times: My painless ten-pound birth. How I learned to ride a bike at a young age. The time she bought me a boom box because I loved rapping so much. The thing I love about these stories is that they’re unique to me, of course, but they’re also the sort of minor mythologies that every family has, the kind of stories that everyone hears from their parents and aunts and uncles, if they’re lucky enough to have parents around. In the song I played that near-universal mother-love against the content of the verses, which was the story about how I went from a kid whose world was torn apart by his father’s leaving to a young hustler in the streets who excelled but was scarred by the Life and eventually decided to

try this rap shit for a living.

The parts where my mother’s voice comes in to the song are surrounded by swirling orchestral fanfare that make the little stories feel epic. And that’s how it feels for everyone, I think, to hear our mothers proudly tell those little stories about what made us special over and over again.

My final show for

The Black Album

tour was at the Garden. Playing Madison Square Garden by myself had been a fantasy of mine since I was a kid watching Knicks games with my father in Marcy. I arrived and the sight of my name in lights on the marquee got me in the right frame of mind. I began to visualize the whole show from beginning to end; in my mind it was flawless. Security at the Garden was nuts; my own bodyguard couldn’t even get in. Backstage I watched my peers come in one by one. Puff was there in a chinchilla. Foxy showed up wearing leather shorts. Slick Rick was there wearing his truck jewelry. Ghostface had on his bathrobe. I had asked Ahmir and the Roots band to join me for the few shows I did before the Garden so we could get the show in pocket, and that night he was extra nervous, but I told him to act like it’s any other show. We both knew that was a lie. Michael Buffer, who announces all the boxing matches in the Garden, announced me, and I did my signature ad-libs. The crowd went bananas.

I started my set off with “What More Can I Say” and I ended the night with “December 4th,” the song I named for my birthday. I ended the concert by “retiring” myself, sending a giant jersey with my name on it up to the rafters. As it was making its way to top of the Garden, I looked into the crowd and saw a girl in the audience crying, real tears streaming down her face. It was all I could do to stop looking at her and focus on the person next to her. My songs are my stories, but they take on their own life in the minds of people listening. The connection that creates is sometimes overwhelming.