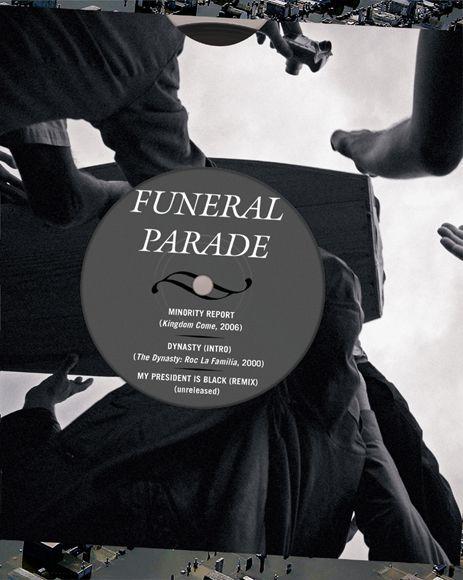

Decoded (26 page)

Authors: Jay-Z

Tags: #Rap & Hip Hop, #Rap musicians, #Rap musicians - United States, #Cultural Heritage, #Jay-Z, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

I

don’t remember exactly where I was in August 2005, but at the end of that month I was mostly in front of the television, like most other people, transfixed and upset by the story of Hurricane Katrina. Most Americans were horrified by what was happening down there, but I think for black people, we took it a little more personally. I’ve been to shantytowns in Angola that taught me that what we consider to be crushing poverty in the United States has nothing to do with what we have materially—even in the projects, we’re rich compared to some people in other parts of the world. I met people in those shantytowns who lived in one-room houses with no running water who had to pay a neighbor to get water to go to the bathroom. Those kids in Angola played ball on a court surrounded by open sewage, and while they knew it was bad, they didn’t realize just how fucked up it was. It was shocking. And I know there are parts of the world even worse off than that.

The worst thing about being poor in America isn’t the deprivation. In fact, I never associated Marcy with poverty when I was a kid. I just figured we lived in an apartment, that my brother and I shared a room and that we were close—whether we wanted to be or not—with our neighbors. It wasn’t until sixth grade, at P.S. 168, when my teacher took us on a field trip to her house that I realized we were poor. I have no idea what my teacher’s intentions were—whether she was trying to inspire us or if she actually thought visiting her Manhattan brownstone with her view of Central Park qualified as a school trip. But that’s when it registered to me that my family didn’t have as much. We definitely didn’t have the same refrigerator she had in her kitchen, one that had two levers on the outer door, one for water and the other for ice cubes. Poverty is relative.

One of the reasons inequality gets so deep in this country is that everyone wants to be rich. That’s the American ideal. Poor people don’t like talking about poverty because even though they might live in the projects surrounded by other poor people and have, like, ten dollars in the bank, they don’t like to think of themselves as poor. It’s embarrassing. When you’re a kid, even in the projects, one kid will mercilessly snap on another kid over minor material differences, even though by the American standard, they’re both broke as shit.

The burden of poverty isn’t just that you don’t always have the things you need, it’s the feeling of being embarrassed every day of your life, and you’d do anything to lift that burden. As kids we didn’t complain about being poor; we talked about how rich we were going to be and made moves to get the lifestyle we aspired to by any means we could. And as soon as we had a little money, we were eager to show it.

I remember coming back home from doing work out of state with my boys in a caravan of Lexuses that we parked right in the middle of Marcy. I ran up to my mom’s apartment to get something and looked out the window and saw those three new Lexuses gleaming in the sun, and thought, “Man, we doin’ it.” In retrospect, yeah, that was kind of ignorant, but at the time I could just feel that stink and shame of being broke lifting off of me, and it felt beautiful. The sad shit is that you never really shake it all the way off, no matter how much money you get.

SOME GET LEFT BEHIND, SOME GET CHOSEN

I watched the coverage of the hurricane, but it was painful. Helicopters swooping over rooftops with people begging to be rescued—the helicopters would leave with a dramatic photo, but didn’t bother to pick up the person on the roof. George Bush doing his flyby and declaring that the head of FEMA was doing a heckuva job. The news media would show a man running down the street, arms piled high with diapers or bottles of water, and call him a looter, with no context for why he was doing what he was doing. I’m sure there were a few idiots stealing plasma TVs, but even that has a context—anger, trauma. It wasn’t like they were stealing TVs so they could go home and watch the game. I mean, where were they going to plug them shits in? As the days dragged on and the images got worse and worse—old ladies in wheelchairs dying in front of the Superdome—I kept thinking to myself,

This can’t be happening in a wealthy country. Why isn’t anyone doing anything?

Kanye caught a lot of heat for coming on that telethon and saying, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people,” but I backed him one hundred percent on it, if only because he was expressing a feeling that was bottled up in a lot of our hearts. It didn’t feel like Katrina was just a natural disaster that arbitrarily swept through a corner of the United States. Katrina felt like something that was happening to black people, specifically.

I know all sorts of people in Louisiana and Mississippi got washed out, too, and saw their lives destroyed—but in America, we process that sort of thing as a tragedy. When it happens to black people, it feels like something else, like history rerunning its favorite loop. It wasn’t just me. People saw that Katrina shit, heard the newscasters describing the victims as “refugees” in their own country, waited in vain for the government to step in and rescue those people who were dying right in front of our eyes, and we took it personally. I got angry. But more than that, I just felt hurt. In moments like that, it all starts coming back to you: slavery, images of black people in suits and dresses getting beaten on the bridge to Selma, the whole ugly story you sometimes want to think is over. And then it’s back, like it never left. I felt hurt in a personal way for those people floating on cars and waving on the roofs of their shotgun houses, crying into the cameras for help, being left on their porches. Maybe I felt some sense of shame that we’d let this happen to our brothers and sisters. Eventually I hit the off button on the remote control. I went numb.

SO I GOT RICH AND GAVE BACK, TO ME THAT’S THE WIN-WIN

It’s crazy when people think that just because you have some money and white people start to like you that you transcend race. People try this shit all the time with successful black people, even with someone like me who was plenty black when I was on the corner. It’s like they’re trying to separate you from the pack—make you feel like you’re the good one. It’s the old house nigger–field nigger tactic.

But even if you do get it into your head that somehow you’re exceptional, that you’ve created some distance between where you are and where you’re from, things like Hurricane Katrina snap you right out of it. I couldn’t forget that those were my kin out there in New Orleans, and that, forget the government, I was supposed to do something to help them. I got together with Puffy and we donated a million dollars to the relief effort, but we donated it to the Red Cross, which is barely different from donating to the government itself, the same government that failed those people the first time. Who knows how much of that money actually made it to the people on the ground?

It also made me think of the bigger picture. New Orleans was fucked up before Katrina. This was not a secret. The shame and stigma of poverty means that we turn away from it, even those of us living through it, but turning away from it doesn’t make it disappear. Sooner or later it gets revealed, like it was in New Orleans. The work we have to do is deeper than just putting Band-Aids on the problems when they become full-blown disasters.

To some degree charity is a racket in a capitalist system, a way of making our obligations to one another optional, and of keeping poor people feeling a sense of indebtedness to the rich, even if the rich spend every other day exploiting those same people. But here we are. Lyor Cohen, who I consider my mentor, once told me something that he was told by a rabbi about the eight degrees of giving in Judaism. The seventh degree is giving anonymously, so you don’t know who you’re giving to, and the person on the receiving end doesn’t know who gave. The value of that is that the person receiving doesn’t have to feel some kind of obligation to the giver and the person giving isn’t doing it with an ulterior motive. It’s a way of putting the giver and receiver on the same level. It’s a tough ideal to reach out for, but it does take away some of the patronizing and showboating that can go on with philanthropy in a capitalist system. The highest level of giving, the eighth, is giving in a way that makes the receiver self-sufficient.

Of course, I do sometimes like to see where the money I give goes. When I went to Angola for the water project I was working on and got to see the new water pump and how it changed the lives of the people in that village, I wasn’t happy because I felt like I’d done something so great. I was happy to know that whatever money I’d given was actually being put to work and not just paying a seven-figure salary for the head of the Red Cross. And I did a documentary about it, not to glorify myself, but to spread the word about the problem and the possible solutions.

That’s what I tried to do with my Katrina donations, and with my work for Haiti in the aftermath of their earthquake and with other causes I get involved with. I also like to make a point about hip-hop by showing how so many of us give back, even when the news media would rather focus on the things we buy for ourselves. But whether it’s public or private, we can’t run away from our brothers and sisters as if poverty is a contagious disease. That shit will catch up to us sooner or later, even if it’s just the way we die a little when we turn on the television and watch someone’s grandmother, who looks like our grandmother, dying in the heat of a flooded city while the president flies twenty thousand feet over her head.

[

Intro: news excerpts

] The damage here along the Gulf Coast is catastrophic. / There’s a frantic effort underway tonight to find / survivors. There are an uncounted number of the dead tonight … / People are being forced to live like animals … / We are desperate … / No one says the federal government is doing a good job … / And hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people … / No water, I fought my country for years … / We need help, we really need help … / In Baghdad, they drop, they air drop water, food to people. Why can’t they do that to their own people? /

The same idiots that can’t get water into a major American city in less than three days are trying to win a war …

1

/ [

Jay-Z

]

People was poor before the hurricane came

2

/ Before the downpour poured is like when Mary J. sang / Every day it rains, so every day the pain / Went ignored, and I’m sure ignorance was to blame / but life is a chain, cause and effected / Niggas off the chain because they affected / It’s a dirty game so whatever is effective /

From weed to selling kane, gotta put that in effect, shit

3

/ Wouldn’t you loot, if you didn’t have the loot? / and your baby needed food and you were stuck on the roof / and a helicopter swooped down just to get a scoop /

Through his telescopic lens but he didn’t scoop you

4

/ and the next five days, no help ensued / They called you a refugee because you seek refuge / and the commander-in-chief just flew by / Didn’t stop, I know he had a couple seats / Just rude, JetBlue he’s not / Jet flew by the spot / What if he ran out of jet fuel and just dropped / huh, that woulda been something to watch / Helicopters doing fly-bys to take a couple of shots / Couple of portraits then ignored ’em /

He’d be just another bush surrounded by a couple orchids

5

/ Poor kids just ’cause they were poor kids / Left ’em on they porches same old story in New Orleans / Silly rappers, because we got a couple Porsches / MTV stopped by to film our fortresses / We forget the unfortunate / Sure I ponied up a mill, but I didn’t give my time /

So in reality I didn’t give a dime, or a damn

6

/ I just put my monies in the hands of the same people / that left my people stranded / Nothin but a bandit / Left them folks abandoned / Damn, that money that we gave was just a Band-Aid / Can’t say we better off than we was before / In synopsis this is my minority report /

Can’t say we better off than we was before

7

/ In synopsis this is my minority report / [

Outro: news excerpts

]

… Buses are on the way to take those people from New Orleans to Houston …

/ They lyin’… / People are dying at the convention center / … Their government has failed them / … George Bush doesn’t care about black people