Decipher (16 page)

Authors: Stel Pavlou

“This is your research, Dr. Scott,” Gant announced, as the epigraphist gasped and ran his eyes the length of the display.

Scott was about to field more questions when an excited scientist wearing similar gear came rushing over and handed Houghton a piece of paper. “This fax just came in for you,” he said. “It's fantastic!”

Houghton read it quickly before passing it around.

The buzz of excitement it generated was matched only by the buzz of high-voltage electricity coursing through the equipment and around the room.

ROLA CORP. Making Energy Work

Â

FAX

Â

TO:

Jay Houghton, Cern, Geneva

Jay Houghton, Cern, Geneva

FROM:

Sarah Kelsey, Chief Field Geologist, Egypt

Sarah Kelsey, Chief Field Geologist, Egypt

DATE:

March 18, 2012

March 18, 2012

REF & SPEC:

410B/C/24794AH-409

410B/C/24794AH-409

Â

Â

Be advised. At 11:03 AM today, ground was broken to sink a well down to a cavity detected 30 feet underground in the region of the Sphinx. A number of similar cavities have also been detected in and around the pyramid site.

Â

Please also: Carbon 60 has been positively identified. Will keep you briefed as and when.

Â

Interesting fact number 2: Erosion damage to the Sphinx shows vertical channels through the horizontal layers of sandstone. Indications of classic flood damage. Subsurface weathering analysis shows deep penetration erosion at a microscopic scale. Stress caused by heat, cold and moisture which takes 1â2,000 years per foot to advance. 4 feet deep on the rear half, 8 feet on the front half suggesting the Sphinx was built in two halves separated by 4,000 years. Makes the Sphinx at least 8,000 years old! When I mentioned this to the archeologist here they got real pissed. Insisted the Sphinx was built in 2,500BC by Pharaoh Kafra. I seriously think they're wrong.

Â

FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY

DISTRIBUTION TO AUTHORIZED NAMES ONLY

NO UNAUTHORIZED COPYING!

DISTRIBUTION TO AUTHORIZED NAMES ONLY

NO UNAUTHORIZED COPYING!

Â

THIS DOCUMENT IS NOT TO BE DISTRIBUTED TO THE PUBIC

“Yallah! Yallah!”

came the surrounding calls. Hurry! Hurry!

came the surrounding calls. Hurry! Hurry!

“Shuuftibi! Bisuurah!”

Look! Quick!

Look! Quick!

The earsplitting whistle that ripped through the dry air to accompany the shouts was a workman's. He whistled again, jamming his grimy fingers tightly into his parched mouth.

They had found something.

Sarah and Eric eyed each other before breaking into a run.

At the well, where steel-mesh collars had been lowered into the hole to support the particulate sandstone sides from collapsing in on the workers, there were signs of digging still taking place at the bottom. Sarah picked her way past trays loaded with bagged artifacts, took up a perch near the edge of the well and peered down.

More assorted bowls and pottery were carefully being passed up, followed by bucketloads of sand, and one agitated Arab worker. A couple of Egyptian Antiquities Police Officers had moved in too. Black greasy Kalashnikovs slung at their shoulders. One was on the radio.

Professor De la Hoy shook his head. He was Chief Archeologist in the Egyptian Department of Antiquities. And was busy to one side of the well, using his own set of dental tools on one particular pot. He was visibly moved. Kept mumbling about some archeological dig in 1893 when the great Flinders Petrie dug at Naqada, 300 miles south of Cairo, and found exactly the same type of pots that he couldn't place in the standard archeological timeline. He ended up attributing them to a “New Race” and they had since been academically ignored. De la Hoy added that 30,000 similar pieces of pottery were discovered beneath the step Pyramid of Zozer at Saqqara. But somehow, Sarah knew that wasn't what was getting to the man. It was the fact that he had spent thirty years of his life on a flawed science.

The dust was thick, taking its time to settle. The grit-caked galebeya of the sole remaining Egyptian at the bottom

of the well was ripped and soaked in sweat. But the excited, wide-eyed expression on the man's deeply tanned face said it all, which was useful, because Sarah couldn't understand a word he was actually saying:

“Hiya daraja! Ajid Daraja!”

of the well was ripped and soaked in sweat. But the excited, wide-eyed expression on the man's deeply tanned face said it all, which was useful, because Sarah couldn't understand a word he was actually saying:

“Hiya daraja! Ajid Daraja!”

He was twenty-five to thirty feet down. Too shallow a depth to have hit the Carbon 60 yet. Scanning the faces above, he reached for his crude hand-brush made from desert broom, when he spotted Sarah. He set about sweeping off sand from a plinth of stone that crossed the width of the well at one end.

Scurrying about on all fours, ignoring the sharp stones that cut into his knees, the busy Egyptian proudly picked out the edge of the stone with his bare fingers. Brushed away more stones and looked up, patting the ground with the flat of his hand, trying to bridge the language barrier with simple signing and body language.

One, he seemed to be saying with a pat. One stone. And under hereâa second. Then three, four, lower and lowerâ

“He's found a step,” Sarah realized. “He's found a set of steps.”

Â

Clemmens pointed at each end of the uncovered step. “It goes about one or two feet deeper into the side of the well's my guess.”

“That answers one question,” Sarah added under her breath so only Clemmens could hear. “These are manmade

ceremonial

tunnels. No way we can pass these off as a natural phenomenon.”

ceremonial

tunnels. No way we can pass these off as a natural phenomenon.”

Clemmens smirked. “Boy, is Douglas gonna be pissed if the media get ahold of this.”

Sarah looked to the other diggers questioningly. “Can we get more workers down there?” she asked. “Dig those steps out?”

The Egyptians sprang into action, lowering one of the smaller men down, although it was clear the superstitious worker who had just climbed out obviously wanted to go nowhere near the well again. Sarah was faintly reminded of Howard Carter's famous 1922 excavation of Tutankhamen's tomb. It had been said it was cursed, as were many ancient Egyptian tombs. But on Carter's dig, people

had

died.

had

died.

A finger jammed in one ear, a radio pressed to his mouth,

Clemmens surveyed the find sharply as he set about briefing Douglas on the other end of the line.

Clemmens surveyed the find sharply as he set about briefing Douglas on the other end of the line.

“We'll need a marquee of some kind. Big. Secure, so we can get the larger equipment in under it. Stop any prying eyes and cameras. We'll need generators. Arc lights. Round the clock support. Yes, sir. I think we're close. And if we double these people's pay we'll be even closer.”

De la Hoy was furious. In his upper-crust English accent he said icily: “What the

devil

do you think you're doing?”

devil

do you think you're doing?”

But Clemmens ignored him. “Oh, and sir? Could somebody get these goddamn archeologists off the site? They're a pain in the butt.” He smiled. Relaxed. “Professor, if you'd be so kind as to haul ass? There's a good chap. Tip top, old bean.”

As De la Hoy was escorted away from the site, the radio hanging at Sarah's hip fizzled into life: “Yeah, Sarah, we're out at the test zone, running that second pass. Over.” It was the geo-phys team, with a ground-penetrating radar unit that was more accurate than the resistivity unit they'd used earlier.

Sarah popped the catch. Thumbed the black transceiver. “Good hunting. Over.”

Static, then a clipped: “Thanks.” It was like listening to astronauts on the moon.

“Just what is it with this weather?” Clemmens moaned, glancing up at the cloudless sky and wiping his forehead with a rag.

“This is the desert,” Sarah said. “It's supposed to be hot.”

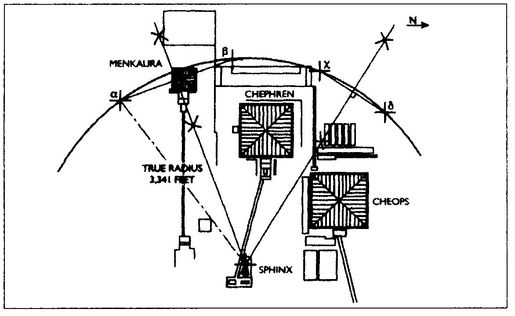

“In March? It's one twenty in the shade,” Clemmens sighed. “This ain't normal 'less it's July.” As the sounds of pick-axes and shovels striking stone below them cracked out in a steady rhythm, Sarah diverted Clemmens's attention back to her map where she'd marked twelve red Xs corresponding to where hollows some way under the bedrock had been detected. And, where the signature for Carbon 60 had also been detected. Clearly, a pattern was emerging.

“I'm tellin' ya, it's a circle,” she said.

“Is that a wager?” Clemmens asked.

“You betcha.”

“How much?”

“How much you got?”

Clemmens checked his pockets. All he had was lunch moneyâa fifty-dollar bill.

By joining the Xs Sarah created an arc. And she was sure this arc was part of a circle, not an ellipse or other curved shape. To confirm this she needed to find where the circle's exact center might be. Mathematics was useless, it would only give an approximation, but a simple pair of compasses and an old engineering trick made up for that. She connected two points of the arc together by drawing a straight line between them and using the compass at each end of the line to draw an arc above and below the line. This formed two new Xs. One above and one below the line. Joining the two Xs created a cross, a perpendicular line that bisected the first line at 90° through its natural center. By repeating the process on the other two points of the are and extending both perpendicular lines downward they eventually met and revealed the true center of the circle, which Sarah was surprised to find was situated directly under the Sphinx.

Clemmens gave her a look. “Not bad for a geologist,” he said. “What if you're wrong?”

“Dad was an engineer,” she explained. “No one got out of the house unless they could tell him how it was built. I'm not wrong.”

“We'll see.”

Since the drawing was the same scale as the map, and the

distance from the center of the circle to one of the original measurement points along the arc was the true radius, Sarah was able to draw in the full circle. From that she provided geo-physics with map references where she predicted they would find further positive readings. They named the test zones: Alpha, Beta and Gamma.

distance from the center of the circle to one of the original measurement points along the arc was the true radius, Sarah was able to draw in the full circle. From that she provided geo-physics with map references where she predicted they would find further positive readings. They named the test zones: Alpha, Beta and Gamma.

“Eric to Test Zone Beta,” Clemmens announced, thumbing his own radio. “Frankie, whatchya got?”

There was a long loud hiss of white noise before the heavy breathless wheeze of Frankie came back at him. “Just done a pass.”

“And?”

Silence. Eric and Sarah exchanged glances. Sarah was chewing a thumbnail and tapping her foot. She wasn't good at waiting.

“Frankie?” Eric demanded impatiently. “Whatchya got? Over.”

A hiss. Then: “We got a positive,” he responded hastily. “Strong and bang on target. We gotta do a second pass but mark us down as a positive. Over.”

“That's it,” Eric said, spinning on his heel excitedly. “That's it!” But Sarah was already scribbling on her map. Her radio springing into life again.

“This is Test Zone Gamma. Over. All passes completeâwe have a positive. Repeat, we have a positive. Over and out.”

“Test Zone Alpha reporting second pass confirmation. We too have a positive ⦠D'you guys know what this means?”

She knew two times pi times the radius of the circle gave the circumference of the circle. And she now knew that there

was

a circle with a radius of 3,341 feet. A quick calculation and Sarah knew exactly what

that

meant.

was

a circle with a radius of 3,341 feet. A quick calculation and Sarah knew exactly what

that

meant.

“We got a circular tunnel nearly three miles around, Eric. Jesus!”

“Three miles? That's like five kilometers at least! That's like the size of a goddamn particle accelerator! And our well here hits a side tunnel that connects to it!”

Sarah was frantic. “Who the hell could tunnel with that kind of accuracy thousands of years ago? They'd need to know pi. They'd need to know trigonometry, geometryâ”

Eric shook his head. “I got a better question: why the hell would they want to?”

“I dunno,” she grinned. “But I told you it was a circle. You owe me fifty bucks.”

Clemmens was slow to dig for it.

Â

The marquee was brought in by truck as part of a supply convoy. Spearheaded by the metallic gold and tinted windows of Toyota Land Cruisers, emblematic of the Egyptian Security Police. Suddenly to get anywhere near the well required authorization that got you through two checkpoints and the gates to two hastily erected chainlink fences that encircled the vast blue tent.

It had taken thirty minutes to build. In that time several more steps were dug out and Clemmens had identified the direction in which the tunnel descended. He mapped out an archway. Sent metalworkers down to weld a steel arch into place and cut out a doorway underneath it through the mesh collars. The remaining expanse of mesh was reinforced through the arch so it wouldn't buckle under the strain of keeping the sides of the well at bay.

Sarah studied the exposed strata. From ground level to six feet down it was solid bedrock. For the next four feet it was pockets of fill and more bedrock. Solid bedrock for a further three feet. Then fill entirely until the steps were reached. It meant someone had meticulously filled this tunnel to capacity a very long time ago. No one was intended to get through.

With the metal support arch in place and the oxyacetylene torch done and dusted, Sarah was carefully lowered down to inspect the wall of sheer fill. The metal archway above looked like a scrap metal homage to a gothic cathedral.

Trusting her instructions would be adhered to as they were hastily translated into Egyptian Colloquial Arabic, she said: “Start at the top. Work your way back and come down gradually. Creating a slope. That way if it becomes unstable it shouldn't collapse in on you. But what I want is to find the roof and walls of this tunnel. When we have those dimensionsâthen we'll know what we're dealing with.”

They were ordered to go back to work.

“Emshi! Emshi!”

“Emshi! Emshi!”

Pick-axes were sharply thrust into the dirt. The fact that everything was damp helped the situation on the one handâit bound the particles together, making it easier to dig without fear of a collapse. But on the other hand it made the work tiring, because for every shovel-load of sand removed, water was the hidden constituent in its weight, and quickly exhausted the diggers.

It took several hours to advance ten feet. But when they had, the dimensions of the tunnel exposed the sheer scale of the subterranean construction. And what had been characteristic of the original exploration of the Great Pyramid now rang true for the tunnels. What faced everyone was a giant stone plug of such enormous magnitude that it beggared belief.

Other books

Gaining Visibility by Pamela Hearon

The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia by Tzouliadis, Tim

Republic or Death! by Alex Marshall

Flykiller by J. Robert Janes

Awakened: Five First Lesbian Sex Erotica Stories by Nancy Brockton

Three Weddings And A Kiss by Kathleen E. Woodiwiss, Catherine Anderson, Loretta Chase

Devil's Tor by David Lindsay

Lazy Days by Clay, Verna

So Over You by Gwen Hayes

Sleeping Dragons Book 1: Animus by Ophelia Bell